Liverpool 2017/18: Toxteth O’Grady

Liverpool 2018: The Killing Moon

Introduction:

Jurgen Klopp has many reasons to smile at present with his team competing for the Premier League title and in the knock out stage of the Champions League.

Under Klopp’s management, combined with what seems to be astute operational management by the club’s commercial and marketing department, the club has also announced a world record pre-tax profit of £125 million for 2017/18.

Reds’ fans won’t give a hoot about the profits as they look forwards with anticipation and trepidation to the remainder of the season, but there is a link between good financial and footballing management depending upon the business model employed by different club owners.

Grinding through the numbers suggests that the club is in good financial shape although a closer inspection reveals that the record figures were mainly due to the sale of Philippe Coutinho.

Even so, compared to the management of the club under Hicks and Gilette a few years ago Liverpool are light years away from the near bankruptcy that they faced as debts piled up and banks came closer to pressing the trigger.

Key financial figures for year to 31 May 2018: Liverpool Football Club and Athletic Company Limited

Income £455.0 million (up 25%).

Wages £263.0 million (up 27%) .

Operating profit before player sales £1.1 million (down 84%)

Player signings £190 million (up 149%)

Player sales £137 million (up 89%)

Owner loans £120 million (down £10 million)

Income:

New income sources are always a challenge for clubs as ultimately they are split into three broad areas, matchday, broadcast and commercial, some of which are more controllable than others in terms of increasing the numbers.

Keeping up with the peer group is the hardest challenge for Liverpool and in this regard the club has done exceptionally well in 2017/18 as the club rose from 9th to 7th in the Deloitte Football Money League, which focuses on club revenue.

Liverpool’s income rose faster than any other club (that has reported to date) for last season as total revenue increased by a quarter, which is an achievement for any business that has been trading for over a century.

Of the ‘Big Six’ clubs (although Spurs haven’t won the title for nearly 60 years and are yet to publish their 2018 results) the income growth in 2017/18 allowed Liverpool to leapfrog both Chelsea and Arsenal last season.

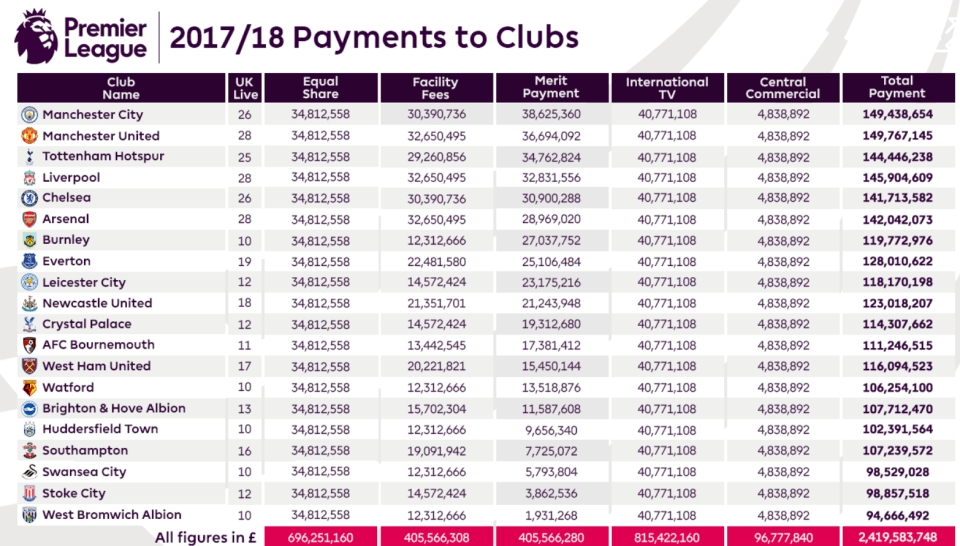

Premier League income is dominated by the big clubs but has increased for everyone nearly every year since its inception in 1992, when Liverpool’s revenue was only £17.5m, which in the Reds’ case equates to a 14% increase every year.

Parting fans from their cash is never an easy task for football clubs but Liverpool have managed to increase matchday income by 82% since 2013 on the back of greater capacity at Anfield and selling more tickets to the hospitality sector.

Every club has a slightly different strategy when it comes to season ticket holders and Liverpool’s is to restrict ST numbers to just 26,000 out of their 54,000 capacity and have many more available to fans on a match by match basis.

Although such an approach does generate resentment from those on the Liverpool season ticket waiting list (presently closed as it could take up to 15 years to get a ST) from a cold commercial basis this policy makes financial sense given the club’s international appeal.

The concept of the football tourist, armed with selfie stick and half and half scarf, provokes merriment from away fans at Anfield but such fans do generate cash even if they are held in contempt by regulars at the club.

Success in reaching the Champions League which meant more sold out matches at Anfield which contributed to the 10% rise in matchday income last season, despite a freeze in individual ticket prices.

Having matches sell out is great but matchday revenue is a combination of attendances, prices and number of matches and Liverpool were relatively successful here in generating over £1,500 per fan over the course of the season, nearly 50% more than present Premier League rivals Manchester City and three times as much as neighbours Everton.

Income from broadcasting increased by 43% due mainly to Liverpool generating £72 million in UEFA TV income as a function of reaching the Champions League final compared to a European free season in 2016/17.

Such is the importance of Champions League progress Liverpool generated more broadcast income that any other English club last season despite only finishing 4th in the Premier League.

Being a club with a large global profile helped drive up commercial income by 13% in 2017/18, partly due to a sleeve sponsorship deal with Western Union and in addition sponsors paying bonuses as Liverpool reached the Champions League final.

Of the commercial deals that clubs have, kit manufacturing and shirt sponsorship are usually the most lucrative, Liverpool renewed their deal with Standard Chartered in May 2018 for an estimated £160 million over four years so this should provide a boost for 2018/19.

Getting hold of a Liverpool replica shirt at present is tricky as practically everyone produced by present manufacturer New Balance has flown off the shelves as sales have hit record levels.

In comparison to the other ‘Big Six’ clubs Liverpool are doing well but there is scope for further growth, Manchester United’s commercial department are legendary at getting companies to pay for the privilege of attaching their products to United’s crest and Liverpool appear to be trying to copy this model of having different commercial partners for the same product in different locations.

Ensuring the club has commercial income growth is an essential feature of setting a club apart from the also rans in the Premier League and it appears that Liverpool are in talks with a variety of kit manufacturers to boost the present £45m a year they generate from New Balance in a deal that expires after 2019/20 to something closer to the £75m that Manchester United earn from adidas.

Success on the pitch makes clubs very appealing for sponsors and the lack of it in recent years is partly why Liverpool have suffered relative to some of their peer group, although this could reverse if Jurgen Klopp starts bringing trophies to Anfield.

Costs

The main costs for clubs are those relating to players, in the form of wages and transfer fee amortisation.

Liverpool’s wages have doubled since 2013 and increased by 27% in 2017/18 reflecting the investment in the squad as Salah, VVD and others were recruited during last season as well as other players earning improved contracts. This meant that overall Liverpool’s wage bill overtook those of Chelsea and Manchester City, although City’s figures should be viewed with caution due to the unusual structure of the club in terms of how costs are treated by the parent company City Football Group Limited, which also owns clubs in Australia, USA and Uruguay.

Liverpool’s average weekly wage (and we fully accept that these are rough and ready figures) jumped from £100,000 to £126,000 a week, allowing Liverpool to compete with other elite clubs both domestically and internationally.

Despite the wage increase Liverpool are paying just £58 in wages for every £100 of income. As a rule of thumb clubs in the Premier League are usually deemed to have good wage control if they are paying out 60% or less of income as wages, so the significant increase in income in 2018 covered the wage rise. If Liverpool don’t make a lot of progress in the Champions League in 2018/19 this ratio could deteriorate.

It is not just players who have benefitted from the generosity of the owner, the highest paid director saw their income rise by 45% to £1,329,000, although this is not overly high by Premier League standards.

By Premier League standards Liverpool’s board are reasonably well paid, but this pales into significance when compared to Daniel Levy’s package of over £6 million at Spurs, although Daniel’s fan club will no doubt point out this is partially linked to bonuses linked to his amazing success at delivering Spurs’ new stadium on time and budget. Those who are suspicious of Manchester City’s finances will have food for thought as City have a zero cost for their directors.

The amortisation cost represents the transfer fee paid spread over the term of the contract signed by a player. So, when Liverpool signed Virgil Van Dijk for £75 million on a five and a half year deal it meant that the amortisation cost is £13.6 million (75/5½) a year.

Liverpool’s annual amortisation cost has doubled since 2013, showing the extent of FSG’s h investment in the playing squad.

In using amortisation, it is possible to get a broader feel for a club’s longer-term transfer policy rather than just a couple of windows of buying a selling within an individual season.

Although Liverpool have invested heavily in players in recent years, they are relative paupers in terms of amortisation compared to the two Manchester clubs and Chelsea as the latter have all been spending large sums on transfers over a number of years.

In terms of player sales, these were substantial, as the departure of Coutinho, Sakho, Lucas and Stewart contributed to a profit of £124 million from disposals. As can be seen from the above chart these figures are volatile and vary considerably from year to year. Sales of the likes of Suarez and Sterling in previous years have been lucrative financially for Liverpool but didn’t necessarily help achieve success on the pitch.

Liverpool also had an interest cost of £7.5 million in 2017/18, although some of this was due to accounting dark arts in relation to amounts owed on player transfers and a £19 million tax bill, again mainly due to accounting issues rather than tax being paid to HMRC.

Profits and Losses

Profit, if you ask the right accountant, is what you want it to be, and there are as many types of profit as there are ex-members of the Sugababes.

A rough definition is that profit represents income less costs, and if this figure becomes negative it becomes a loss.

The headline figure in the Liverpool press release was a world record profit of £131million, before taking into consideration finance costs and tax. Taking such a profit figure as a measure of success is okay, but it includes some items which are volatile (such as player sales gains, redundancy costs and player write-downs).

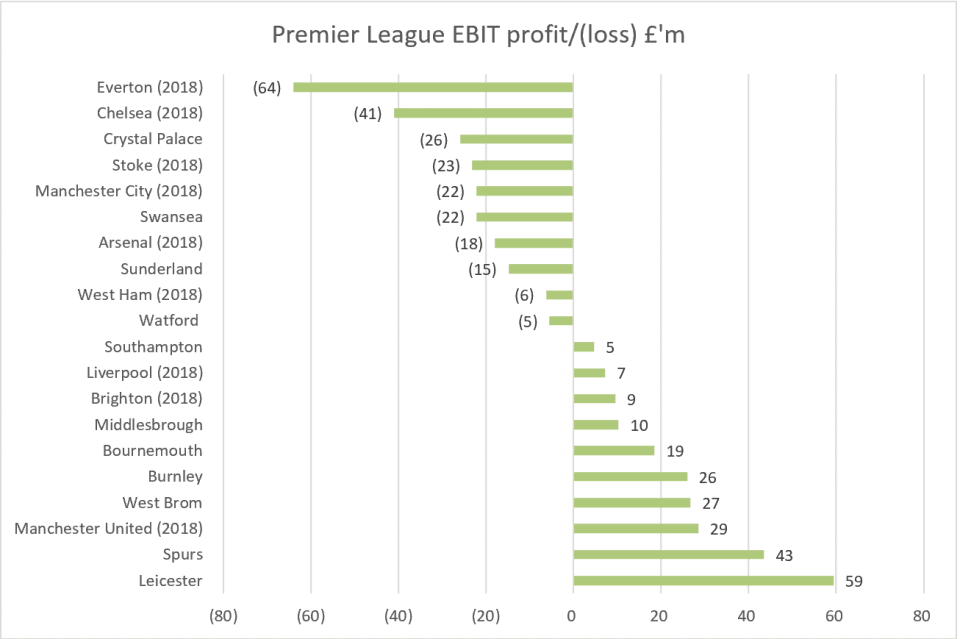

Stripping out the above distortions gives something called EBIT (earnings before interest and tax) profit, which is a better measure of recurring profits excluding the non-recurring transactions.

Liverpool’s EBIT is far lower than the operating profit, but it does show that the club is capable of making profits without having to rely on player sales. This is a good sign as there are some clubs who have suffered significant losses from their day to day activities and so player sale profits become a necessity rather than a bonus.

Liverpool’s EBIT losses worked out at £140,000 a week in 2017/18, reasonable but not spectacular by Premier League club standards.

If non-cash costs such as player amortisation are stripped out, the position however improves, and Liverpool have an EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation) profit of a far more impressive £95 million.

EBITDA is an important profit measure as it is the closest to a ‘cash’ profit that analysts use to assess a business and shows how much the club has to invest in player acquisitions from its day to day activities. Liverpool have made over £339 million in EBITDA profit over the last six years but have invested more than that in improving the squad.

Player trading:

Liverpool had a record year in 2017/18 in terms of player purchases and sales, but the net spend was broadly the same as in 2015 and 2016 at £58 million.

Compared to their peer group, Liverpool’s spending is very modest.

Since the end of the season the board have backed Jurgen Klopp in the summer 2018 transfer windown with a net £181 million on new signings such as Allison, Fabinho and Keita.

Liverpool were owed £169 million by trade creditors, this will mainly be for player transfers but at the same time owed others £148 million

Funding the club

Clubs usually have a choice between third party loans (which attract interest payments) owner loans (which may or may not charge interest) and shares (which occasionally pay dividends).

In the case of Liverpool, the club have focussed on owner and bank loans. Liverpool have an overdraft facility at the bank of £150 million but at 31 May 2018 ‘only’ had used £56 million of this available facility. In addition, Liverpool owed FSG £100 million for a loan in respect of stadium expansion.

A look at the cash movements on borrowings shows that Liverpool appear to have peaked in terms of their debts and are in a position to repay some of the sums due, as £30m was given back to the bank and FSG in 2017/1. The large investment in players in 2018/19 may have resulted in the overdraft increasing again.

Conclusion

Liverpool have had a strong, but perhaps not as spectacular a year financially as has been reported elsewhere. Money spent on infrastructure in previous years has borne fruit in terms of generating extra income and the club has invested record sums in player purchases in the ambition of reaching the Holy Grail of a Premier League title.

This level of investment will have to continue if Liverpool want to consistently challenge to the two Manchester clubs for titles and trophies. Manchester United have an advantage in terms of stadium capacity and commercial deals, Manchester City have the backing of owners will limitless funds. The three main London clubs seem to be at a hiatus at present and it will take time to work out what are the ambitions of their respective owners.