Sheffield United 2017/18: Geisha Boys & Temple Girls

Introduction

Championship finances are the most mind numbing in any division in the professional game and Sheffield United have just produced their accounts for 2017/18.

Having to compete against clubs with the benefit of parachute payments as well as some with rich benefactors means that wages are high, and losses are common.

Relative to other clubs in the division was always a tough task but a seaason of consolidation in 2017/18 has been the platform for potential promotion in the current season.

I must confess to always liking Sheffield United as when I was a kid their Admiral kit was the one in the catalogue that looked cooler than a strawberry Mivvi and they had the magnificent Tony Currie playing for them.

Sheffield United’s finances showed the odds against which the club has had to struggle but a good manager and a goalscoring machine in Billy Sharp have helped keep the club competing in the Championship.

ey Financial Highlights for year ended 30 June 2018

Turnover £20.0 million (up 76%)

Wages £19.0 million (up 90%)

Pre-player sale losses £10 million (up 30%)

Player sale profits £8.4 million (up from £2.7 million)

Player signings £3.9 million (up from £3.1 million)

Income

Winning promotion to the Championship in 2016/17 meant that Sheffield United, like all clubs who went up, had access to potentially higher income sources from the three main activities, matchday, broadcasting and commercial.

Income from matchday rose by 34% to £8.7 million mainly due to average attendances rising from 21,892 to 26,854 as a combination of the attractiveness of Championship football, local derbies against Wednesday and Dirty Leeds and many away teams bringing full allocations.

Local rivals also have decent matchday income by Championship standards but the Blades figures for a side that has not been in that division for six years suggests the club has a very solid fanbase that is likely to sell out Bramall Lane should they be promoted to the Premier League (note figures are for 2016/17 unless clubs have published their totals for last season, which explains why there are some teams in the table who are now in other divisions).

Due to the Championship being on Sky Sports on a far more regular basis than Leagues One and Two, broadcast income quadrupled last season as the EFL TV deal is split 80%/12%/8% between the three divisions.

Every club in the Championship receives a solidarity fee from the Premier League (about £4.3m) a flat sum from the EFL from their Sky deal (about £2.2m) plus a ‘facility fee’ of £100,000 for a home match and £10,000 for an away match for those which are chosen for live broadcasts.

Relegated teams from the Premier League also receive parachute payments of between which completely distort the relative income of clubs in the Championship, this is estimated to be worth about 7 points a season to clubs in the first year of receiving such parachutes.

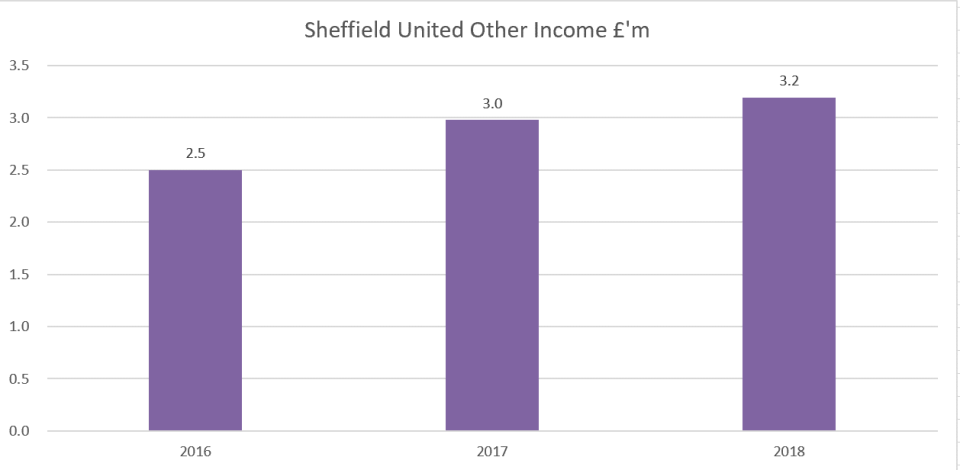

Income from ‘other’ sources is mainly from commercial deals, retail/merchandise and for some clubs conferencing/events, this showed a modest 7% rise for the Blades last season.

Sheffield United are in the bottom quartile of the Championship when it comes to other income and this is something they will no doubt try to grow if they are successful in the Championship and beyond as sponsors like to be associated with top division sides due to the high television profile.

Having the benefits of being in the Championship means that Sheffield United had a much more balanced split of income from the three sources compared to the previous year but there is clearly an opportunity to increase the ‘other’ stream.

Unlike those in receipt of parachute payments, Sheffield United have to budget for income in the £20 million bracket with a number of similar sized teams and this means that it is tougher, but not impossible, to be competing at the top of the Championship.

Costs

Nowadays the most significant costs for a club are in relation to player wages and transfer fees and here Sheffield United had some advantages and some disadvantages having come up from League One the previous season.

Going up resulted in a 90% rise in wages as many players who were responsible for promotion to the Championship were awarded enhanced contracts as well as the Blades having to offer more money when recruiting in 2017/18 to ensure the wages they offered were competitive for the division.

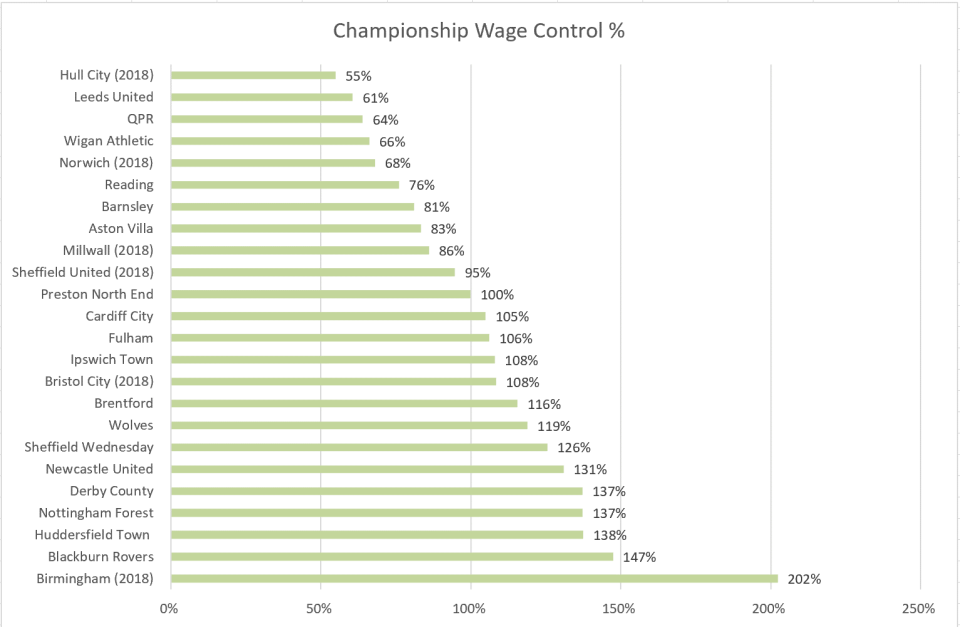

Leeds’s relatively low wage bill may surprise many but there is a significant difference between those clubs such as Sheffield United and those that still benefit from parachute payments with many players reluctant to move and take a pay cut.

Income for nearly all clubs in the Championship barely covers wages and this is true too for Sheffield United who paid out £95 in wages for every £100 of income.

Keeping wages under control when there is a potential £100-120 million a year windfall in the Premier League from TV income is very difficult to resist and this explains why some clubs gamble in terms of their wage bills even if it runs the risk of breaching FFP limits, which restrict losses to £39 million over three seasons.

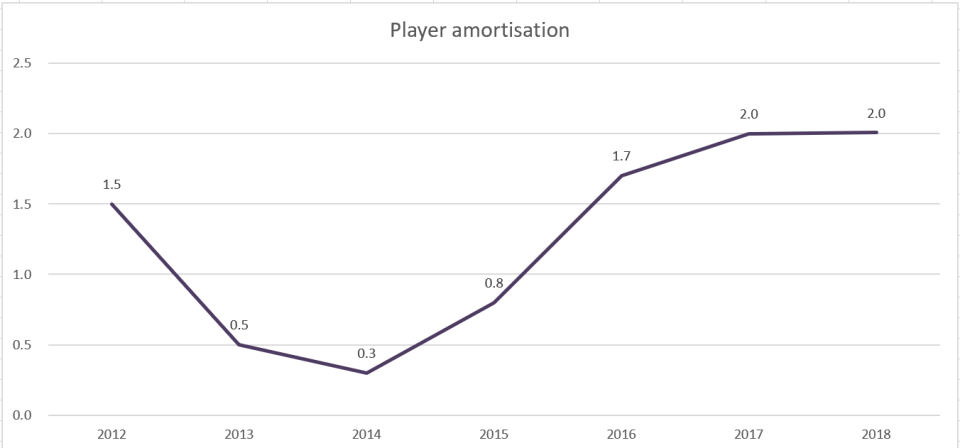

Every player signed for a fee also adds to costs in the profit and loss account via transfer fee amortisation, which is calculated by dividing the amount paid over the contract period. So, when Sheffield United signed Richard Stearman for an estimated £900,000 on a three-year deal this works out as a £300,000 amortisation charge each year.

Amortisation for Sheffield United was broadly similar to that of the previous season in League One which may be reflective of boardroom struggles at the club and owners who were reluctant to spend large sums on players.

High amortisation fees reflect those clubs that have had a long-term investment in recruiting players on big transfer fees and once again those clubs who are in receipt of parachute payments have an advantage here as they have more income to spend on players and also have transfers from when they were in the Premier League.

Other costs, including the likes of rent (£360,000) electricity, marketing, transport and insurance increased by 30% to £8.4million, reflecting the extra burden that clubs incur in the Championship.

Profits

Reference is oftern made to profits when discussing club finances but you have to be careful as there are as many types of profit as there are opening batting combinations for the England cricket team.

Subtracting expenses from income gives a profit figure, but some expenses are erratic in nature and sometimes excluded when trying to determine a club’s underlying financial health for the season.

Each profit figure shown has a slightly different view of the club and they are best considered together to highlight those costs which are significant.

The simplest profit is to deduct all day to day costs from revenue, before considering borrowing expenses, and this is called operating profit. Here Sheffield United made a relatively low loss of £1.7 million last season.

A look at the above figures shows there has been much volatility in relation to profits and losses from year to year. This is mainly due to one off transactions which distort the numbers, such as profits on player sales and in the case of Sheffield United in 2014 a £34.5 million loan being written off.

Most analysts ignore finance, tax and one-off costs to create something called EBIT (Earnings before interest and tax) which represents the club’s underlying profit, and for Sheffield United in 2018 these increased losses to £10 million.

The EBIT figure shows that running Sheffield United is a frighteningly expensive business as the club has effectively lost £150,000 a week from trading over the last seven years and therefore the club needs to generate income from an additional source, and that source if player sales. However, the Blades are far from towards the top of the EBIT losses table as many other clubs have huge running losses.

Sheffield United made a record profit of £8.4 million in 2018 from player sales and these appear to be linked to sell on clauses from the like of Harry Maguire and Kyle Walker.

Player Trading

Sheffield United spent a modest £3.9 million on new players in 2017/8 and after considering player sales had a net income of £4.5 million. In recent years the club has used player sales to balance the books with sales exceeding spending five times in the last seven years. The club has shown it’s the quality of the sums paid combined with astute management rather than the amounts themselves that can deliver a promotion challenge in the Championship.

According to TransferMarkt (and I know it’s not very accurate but better than nothing) the club has spent about £6 million on players in 2018/19 which is more than offset by the transfer of David Brooks to Bournemouth.

Funding

Clubs get funding from three sources, bank loans, owner loans (which may or may not be interest bearing) and shares issued to investors.

Sheffield United are controlled by Kevin McCabe and Prince Abdullah who have fallen out with one another and are involved with unpleasant legal battles. Whatever the club is worth in the Championship it could be sold for £150 million in the Premier League should promotion be achieved.

The partnership between the two parties was initially responsible for paying down the debts of the club but there have been little new borrowings in recent years.

Conclusion

Sheffield United have done extremely well to be at the top end of the Championship on a relatively low budget with owners who are reluctant to put in further cash until their dispute has been concluded. Realistically losses of about £10-12 million this season are likely to be the case, but the sale of David Brooks should offset some or all of them. How long the club can rely on player sales to balance the books in a division that generates higher losses than any other in Europe is uncertain.

Credit has to be given to Chris Wilder and his team for getting on with the day job, making smart loan to buy signings (Oliver Norwood potentially is looking at his third promotion to the Premier League in three seasons with different clubs) and ignoring the boardroom shenanigans.

If the club does not go up this season a lot will depend on Billy Sharp to maintain his prolific scoring to help the Blades in 2019/20 and whilst he is getting no younger the likes of Jermaine Defoe and Glenn Murray have shown that age is not necessarily an issue if you know how to hit the back of the net.