Leeds 2018: Heartland

Overview

Standing on the brink of promotion to the Premier League, playing exciting football and with a cult hero as a manager, Leeds United are cool to like again.

The club’s recently published accounts show that this success hasn’t come free but by the standards of the Championship Leeds have been a model of restraint compared to other owners who have gambled with the existence of their clubs.

Elland Road regulars have plenty of experience of improper owners and at present they seem to be operating with a competitive budget without going overboard.

Very few clubs get promoted making a profit and whilst Leeds are unlikely to do so themselves at least the level of losses incurred will be modest compared to other clubs who have gone up recently.

Revenue

EFL rules encourage clubs to split their revenue into at least three categories, matchday, broadcast and commercial.

Every club is trying to maximise all revenue sources at present due to rapidly rising wages, but Leeds were one of the very few who have been in the Championship for a few years to increase all type.

Various other revenue streams are also shown by some clubs (Leeds separate out catering and merchandise for example) but for the purposes of consistency they are all added to the ‘commercial’ heading.

Average attendances at Elland Road were 31,521 in 2017/18, up nearly 4,000 from the previous season, which contributed to a 10.6% increase in matchday income.

Nearly all the additional matchday income came from higher attendances as average revenue per fan has been broadly static for the last five seasons, with 2012/13 being higher partly due to good cup runs that season.

Sunderland, Sheffield Wednesday and Bolton haven’t published their results for 2017/18 yet (all three have reasons to hide the numbers) but for a team that finished 13th in the Championship last to have the second highest matchday income in the division is a sign of the club’s potential.

Income from broadcasting is a thorny subject for Leeds fans as whilst they are regularly chosen for live matches on TV this causes maximum disruption for fans planning their weekends and minimal extra income for the club.

Sky pay £100,000-£140,000 for home Championship matches (and £10,000 for away matches) but compared to parachute payments for those clubs relegated from the Premier League this is miniscule.

Non-parachute payment receiving clubs such as Leeds start each season in the Championship at a huge disadvantage, with research showing that those clubs recently relegated have a seven-point head start due to their extra PL funding.

On the other hand, some sides recently such as Sunderland and Wolves have dropped straight out of the Championship into League One despite receiving parachute payments, mainly due to having disaffected players on huge contracts refusing to move on due to the money they are earning.

The revenue generated from commercial deals and sponsors is where Leeds had the most impressive growth in 2017/18, with an increase of 33% compared to the previous season.

First in the commercial income table by a street is an impressive performance by Leeds as the club leveraged on the goodwill towards the new owner and made the most of being a big single club city.

Income from commercial sources in the Championship included catering (up by £1 million) merchandising (up £1 million) and general sponsorship (up £3 million) but overall Leeds success here helped give additional funds to be reinvested into the playing squad.

The fact that Leeds had more commercial income than half the clubs in the Premier League shows that the potential here is significant if the club is promoted.

Total income over £40 million is very impressive for a club not in receipt of parachute payments and should ensure Leeds are competitive at the top of the division regardless of whether they go up.

Costs

Overall costs for Leeds increased significantly in 2018 and it will come as no surprise to fans that this was driven mainly by a rise in player costs.

Staff costs rose by over £10 million in 2017/18 although this would include redundancy payoffs for Thomas Christiansen and Paul Heckingbottom (along with their coaching staff).

Nevertheless, despite this increase Leeds were only about mid-table in the Championship wage table last season, as the clubs with parachute payments were able to afford higher sums to players and management.

In terms of wage control Leeds, despite the increase in costs, only paid out £77 in wages for every £100 of revenue, compared to a Championship average of £108.

For any club in the Championship it is a constant battle between gambling on player investment to increase the chances of promotion which if unsuccessful could put the whole future of the club in the balance.

Financial Fair Play (FFP) in theory was introduced to try to prevent this but doesn’t seem to have worked in the Championship to date, with last minute rescues of the likes of Villa and Bolton being the only reason these clubs haven’t gone into administration or worse.

Birmingham being fined 9 points is hardly surprising given that the club spent more than twice their revenue on wages, what is surprising is that other clubs have not been subject to a similar fate.

In terms of transfer fees, these are spread over the life of the contracts signed by players in what are referred to as amortisation costs.

Ezgjan Alioski was signed by Leeds for £2.2m from Lugano in August 2017 on a four-year deal, so that would normally work out at £550,000 (£2.2/4) a year in amortisation costs.

Leeds total amortisation cost, which is the figure that represents all transfers, increased by 50% in 2017/18 as the club invested in Forshaw, Jansson, Saiz, Roberts, Alioski and others for million pound plus transfer fees.

Spreading transfer fees via amortisation reduces the volatility of the cost of transfer fees in a single season and reflects a club’s long-term spending on players.

Amortisation and wages together as a proportion of revenue was 97%, which meant that Leeds had little left to pay for the other day to day running costs of the club, such as rent (£2.2 million) depreciation (£1.6 million) and so on, with ‘other costs’ in total coming to over £17 million.

Profits and losses

Subtracting costs from revenue gives a profit or loss figure for the year and Leeds had an operating loss from day to day transactions of just under £20 million for 2017/18.

Big losses are incurred in the Championship by nearly every club as owners commit to pay the wages and transfer fees on signings that they hope will result in promotion.

In the Championship losses were £505 million last season (and that is without Sunderland, Sheffield United and Bolton) which shows the extreme pressures of trying to compete in the division.

Championship clubs all made operating losses last season and the only way for these to be financed is via player sales or owners investing money via loans or shares.

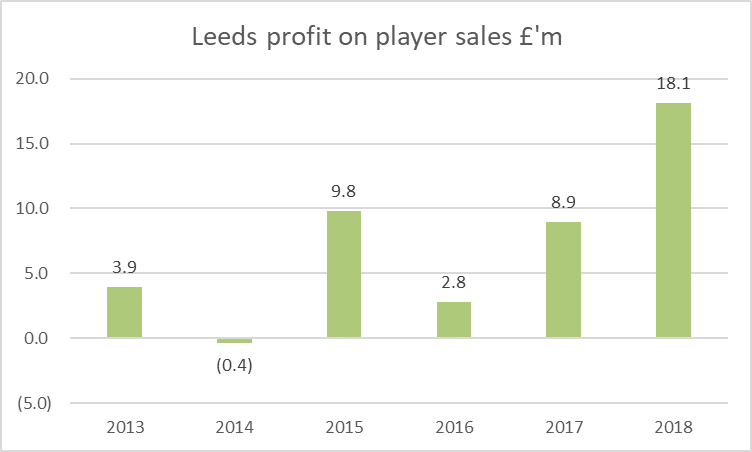

Yearly profits from player sales have been beneficial for Leeds recently, and Liam Bridcutt’s and Chris Woods’ departures, along with some sell on clauses on previous disposals, were the main drivers of the £18 million profit on player sales last season that absorbed most of the operating losses.

Championship clubs managed to recoup over £210 million of the losses via player sale profits but this still leaves a big gap to be plugged by owners.

Letting players go does generate cash but also has a detrimental impact on the quality of the remaining squad but is a financial necessity at times, fortunately for Leeds good cheap recruitment and an impressive academy scheme have improved the quality of football this season.

Excluding costs such as amortisation and depreciation (depreciation is the same as amortisation except this is how a club expenses other long-term asset such as office equipment and properties over time) then another profit figure called EBITDA (Earnings Before Income Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation) is created. This is liked by professional analysts as it is the nearest thing to a cash profit figure.

Struggling to generate cash from operations is common in the Championship but is does mean that clubs must increasingly hope that owners will make up the deficit.

EFL rules allow clubs to lose for FFP purposes (officially called Profitability and Sustainability in the Championship) £39 million over three seasons, but some costs (infrastructure, academy, women’s football and community schemes) are excluded from the calculations.

An estimated P&S profit of £1.6 million over the last three seasons suggest Leeds, even if they are not successful this season, are well within the limits and would not need a fire sale of players during the summer of 2019.

The actual details of P&S calculations for EFL Championship clubs are unknown, prompting much speculation and anger amongst fans who are unsure whether or not their club is subject to ‘soft’ sanctions, which are not publicised, but Leeds are almost certainly not being punished for these given the relatively prudent way the club is run.

Player Trading

Leeds spent £28 million on new signings in 2017/18 on many signings as the two new managers tried to mould squads. The sale of Chris Wood offset a large proportion of these player purchases.

The large spend on players is why the amortisation charge in the profit and loss account is so high. Fans often point out that clubs also sell players and that net spend is a better measure of a club’s investment in talent but again Leeds here have been relatively modest by the standards of the division.

Leeds have been building up the squad in recent seasons, which had a total cost of £37 million at then end of 2017/18. The appointment of Bielsa as coach in the summer of 2018 resulted in a further estimated net spend, mainly on Patrick Bamford, of about £4 million.

Funding

Clubs can obtain funding in three ways, bank lending, owner loans (which may be interest free) or issuing shares to investors. The tie up with SF49’ers brought in share investment of £11 million and there was net borrowing of about £2.5 million in 2017/18.

Summary

Leeds had a hit and miss season in 2017/18 on the field, but the club’s strong revenue growth meant that it was in a strong position from an FFP perspective at the start of the current campaign.

It’s on a knife edge at present whether the club will go up automatically, but a playoff position is guaranteed. Promotion to the Premier League would see revenues rise by at least £100 million and the club is in a strong position given the size of the city and its history to sign some lucrative deals.

Leeds are certainly one of the best three teams in the division this season, but their biggest problem might arise is if they have a chance and fail to make automatic promotion on the last day of the season if the playoff positions are already finalised, as their potential opponents could rest the squad for the final fixture.

Promotion this season will be great for fans, but even if they fail to do so the club is in a strong position financially both in the short and medium term from the figures it has published.

Date Summary