Newcastle United 2017/18: Apply Some Pressure

Introduction

Mike Ashley, Newcastle United’s unloved owner, has finally submitted the accounts for the year ended 30 June 2018 for public scrutiny as The Toon became the final Premier League one to produce results for 2017/18.

In the club’s first season back in the Premier League after winning the Championship Newcastle reversed the big losses and managed to reduce wages from 2016/17, the latter of which is a first for a promoted club.

Kind words are in short supply in Tyneside for Ashley, who bought the club in May 2007 and has overseen two relegations since then.

Easy to criticise, and hard to love, but is Ashley as bad as some make out, given that he has lent the club over £140 million interest free, and invested a similar sum in buying shares in the club too?

A deeper look at the numbers is required to give a broader assessment of Ashley’s stewardship of the club, is he the Freddie Kreuger of football owners or is there some method to the apparent madness of his period at the club?

Revenue

Starting at the top of the profit and loss account, Newcastle’s total revenue doubled to £179 million but is over £200 million lower than that of Spurs, it was only £16 million less when Ashley took over.

Having money is one thing, and Newcastle have now generated revenue of over £1 billion under Ashley’s ownership, whether that money has been spent wisely is another matter.

Looking at total revenue for 2017/18, Newcastle had the 8th highest in the Premier League, although there is an element of chicken and egg as prize money is linked to the final position in the table.

Easily the biggest revenue stream last season was broadcasting, which generated over £126 million for Newcastle, partly due to promotion, partly due to prize money (each additional place in the Premier League is worth an extra £1.9 million) and partly due to the club being popular with broadcasters (each club is paid for ten matches in the basic fee and every additional match shown live is worth an extra £1 million, and Newcastle were shown live 18 times in 17/18).

Year by year volatility for broadcast revenue is also due to combination of which division the club is in and the renewal date for broadcasting deals (the present one kicked in in 2016/17) with Newcastle earning £652 million in total during the Ashley era.

Income from broadcasting in the Championship for non-parachute payment clubs is a basic of about £6.5 million a year, plus £100-£140,000 for every home match shown live on Sky, which shows the importance of being back in the top flight.

Some Premier League clubs generate additional broadcast income by being in UEFA competitions which are worth up to £80 million for winning the Champions League, but other than that the distribution of broadcast income is relatively democratic.

A huge gap therefore exists between those clubs who are in the Champions/Europa League and those that do not, although if Newcastle does qualify for the latter Thursday night trips to the Balkans and Malta are for the dedicated and/or insane only.

Commercial income for 2017/18 nearly doubled to £28 million, but critics of Mike Ashley identify this area as his biggest failing at the club as this has hardly increased since he first walked into the club.

Over at Spurs, commercial income has exceeded the £100 million a season mark on the back of a year at Wembley and Champions League participation.

Commercial income is the one area that clubs can independently grow and in doing so increase the budget for the manager.

Knockers of Ashley will point out he uses St James Park as an advertising vehicle for his Sports Direct cheap and cheerful sports emporium, and he should be generating more commercial income than any other club in the division.

Just £385,000 was earned by Newcastle from Sports Direct last season for this advertising but the club also spent nearly £1.5 million itself buying goods back from SD .

Until the club is sold to a new owner it will be difficult to tell if Ashley has missed a trick in terms of commercial sales but looking at the table overall (and Everton’s is inflated by some unusual naming rights for the training ground) Newcastle are broadly where you would expect them to be for a non ‘Big Six’ club.

Getting fans to turn up at St James’ Park for every match is relatively easy given the loyalty of the locals but getting more money out of them is more of an issue.

Gallowgate end regulars haven’t had to pay more for season tickets following a long term price freeze by Mike Ashley some years ago which explains why the revenue per fan barely changed last season, although individual matchday tickets, which are as difficult to find as a virgin in the Bigg Market on a Saturday night, did go up in price.

Lack of UEFA competition participation and the high prices that can be charged when facing glamourous European opponents is the main reason why Newcastle are so far behind the ‘Big Six’ in terms of matchday revenue, along with having fewer football tourists visiting the North East.

Costs

In the history of the Premier League, no club has ever had a reduction in the wage cost following promotion from the Championship…until Newcastle United in 2017/18.

Newcastle’s wage total fell by sixth last season, although it could be argued that the figures from 2016/17 were distorted by large promotion bonuses and the club accelerating some wages from future years into the Championship accounts via some eyebrow raising accounting that increased wages by £22 million in 2016/17 and decreased the total by £10 million the following season.

Getting wages under control has been one of Mike Ashley’s main ambitions since acquiring the club and with the club paying out just £52 in wages for every £100 of revenue this was easily achieved in 2017/18.

The danger level for wages according to UEFA for a top division club is 70% of revenue and if Newcastle had been at this level then wages would have been £125 million, placing The Toon between Leicester and Everton in the wage table.

Having a bottom half of the table wage bill means that last season’s tenth place finish was impressive, but fans feel that investing more in the squad would give Benitez an opportunity to compete for a European slot.

Unless there is a change in ownership though it is unlikely that this strategy will change as Premier League existence, rather than competing for trophies, appears to the limit of Ashley’s ambition.

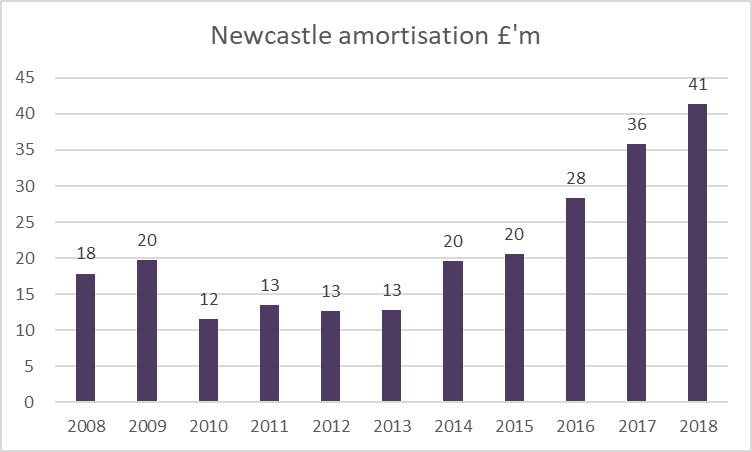

Newcastle’s other main expense in relation to players is transfer fee amortisation, which is a non-cash expense, but all clubs show it in the accounts.

Dividing a transfer fee by the contract length is how amortisation is calculated, so when Newcastle signed Jacob Murphy for £10 million on a four-year deal in July 2017 this works out as an annual amortisation cost of £2.5 million (£10m/4).

Every Newcastle fan will point out that historically Mike Ashley has been reluctant to spend money on players and this certainly held true in the early years of his reign but the club’s mid-table position in the amortisation table suggests that in the last 2-3 years he has relaxed the policy to a degree.

Reducing costs to a minimum is a hallmark of how Mike Ashley runs all his businesses and it is impressive that the ‘other costs’ of Newcastle, which covers all the overheads such as marketing, HR, maintenance, insurance and so on are still lower than those of the first season in which he had control of the club over a decade ago.

Profits

Costs subtracted from income gives profit and Newcastle announced an £18 million profit in a press release compared to a £91 million loss for the previous season.

Understanding profit is a tricky issue though, as there are many variants so care must be taken and it is unwise to rely on just a single profit figure, especially one produced by a marketing department which may want to promote a particular message to either fans or potential buyers of the club.

Newcastle’s turnaround compared to the previous year, however expressed, is spectacular and reflects the additional income from being in the Premier League and cost control in terms of player wages in a division that is less profitable than many perceive.

The early years of Ashley’s reign were loss making and the only way these losses can be funded is through player sales or the owner injecting money.

Total operating losses under Ashley since 2008 come to £140 million but player sales profits more than cover this at £184 million, so this shows the approach taken by the owner.

If you strip out the one-off transactions and amortisation (as it is a non-cash expense) we get to a profit measure called EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest Tax Depreciation and Amortisation). This is the figure most focussed on by city analysts and valuers, at it is a sustainable cash proxy for profit. This was a record £61 million in 2017/18 which meant that the club was generating over £1 million a week in cash from its day to day activities.

Player trading

Mike Ashley’s reluctance to spend money in the transfer market is legendary. In the period since he bought the club, he has spent £382 million on players and generated player sales income of £272 million.

This gives a net spend of just £110 million over the period, although this is distorted by £94 million of this arising in 2015/16 during Steve McLaren’s disastrous spell at the club.

Compared to the rest of the division Newcastle’s recruitment in 2017/18 was low and this was part of the reason why fans were so hostile towards the owner, fearing his reluctance to spend was increasing the chances of relegation.

Debts

Mike Ashley lent the club a further £10 million during the 2017/18, but was repaid this later in the season, meaning his total interest free loans stayed at £144 million. The club also had an overdraft at 30 June 2017, presumably used to pay the promotion bonuses, but this was wiped out when the Premier League broadcast income for 2017/18 started to flow to the club and by the end of the season Newcastle had £34 million in the bank.

Since the year end Ashley has been repaid a further £33 million taking his loan down to £111 million, which apparently won’t be repaid until the club is sold.

In addition to the loans Ashley has invested a further £134 million in shares in the club, taking his total investment to £278 million. Rumour is he is trying to sell if for £300-350 million.

Conclusion

Newcastle did take a gamble in not investing in players in 2017/18 and the risk of relegation was significant until the last third of the season when results improved.

Mike Ashley’s financial strategy appears to have been one of careful cost control to impress potential buyers. This is borne out when plugging in Newcastle’s financial figures into the Markham Multivariate Model used to value Premier League clubs, which churned out an eyebrow raising figure of £442 million, mainly due to excellent wage control, significant prize money on the back of Benitez’s management and a sold-out St. James’ Park for every match. This feels too high a figure but does show the potential of the club to an owner willing to take more risks than the present one. Adjusting for the wages provision reduces the value by about £40 million.

The club’s unusual accounting in relation to wages suggests that, a bit like some of Ashley’s recently acquired retail stores, it has been subject to some window dressing to make things look better than they are.

Data Summary

2 Comments

Bobbi flekman

A little note on wages, you say: “Newcastle’s wage total fell by sixth last season, although it could be argued that the figures from 2016/17 were distorted by large promotion bonuses and the club having many players out on loan whilst paying their wages which according to some sources cost the club over £30 million.”

The bonus structure is not the distortion here as the bonus structure for 2017/18 was published in the local press and, if true, suggests that the bonuses for 2017/18 were around £13m which was more than the promotion bonuses the year before.

The distortion is in the provision put in 2017 of £20m in wages. This was explained as wages for players under contract but had no future at the club. £10m of the provision was used in 2017/18 and £10m remains on the balance sheet. The effect is that wages in 2017 were really £94m and in 2017/18 they were £102m which is more in line with what we’d have expected.

This puts us up a place in the wages table, close to that of West Ham.

Why this was done is guesswork, it could be to fudge FFP or simply to put all the bad news in one year and make the club look more attractive to investors.

The Baron

Good spot thanks for that.