Wolves 2016/17: Far Far Away

Introduction

Wolves have been sensational in the EFL Championship this season, and this has prompted critics to question the role of superagent Jorge Mendes, and the owners Fosun International, who acquired the club in 2016.

We’ve taken a look at how the club has fared financially in the first year of Fosun’s ownership, and its position in terms of Financial Fair Play (FFP).

The club has just announced losses of over £23 million for 2016/17, but that doesn’t seem to have stopped its spending, so are they breaking the rules?

Income

Not all clubs have announced their results for 2016/17 yet, but most clubs are showing higher income than in the previous season. The average income of the 16 clubs that have reported to date (which excludes some big hitters such as Newcastle and Leeds) is £32 million.

In 2015/16 the average for a Championship club was £23 million. The main reason for the increase is due to a combination of higher parachute payments, along with a new TV deal in the Premier League, which drips down to the Championship in what are called ‘Solidarity Payments.

Like all clubs Wolves earn their income from three sources, matchday, broadcasting and commercial/sponsorship.

The table shows how much Wolves benefitted from being in the Premier League in 2011/12 but also how much the club was reliant on parachute payments for the next four seasons. Those parachute payments expiring in 2015/16 are partially responsible for the significant losses recently released.

Matchday income in 2016/17 was up 22%, as fans bought into the investment by Fosun in the playing squad. Finishing 15th was therefore meant that the club failed to meet expectations of all concerned on the pitch.

Attendances averaged just over 21,500, up about 1,300 on the previous season.

Broadcast income was down 42%. This was due to the Wolves four-year receipt of parachute payments finishing the previous season.

The situation would have been worse but luckily the club was fortunate that the Premier League signed a new TV deal for 2017/18, and a fixed percentage of this is allocated to the EFL in what are called solidarity payments. This was worth about an extra £1 million to all clubs in the Championship, peanuts by Premier League standards, but still very useful to those further down the food chain.

Wolves’ commercial income was the biggest contributor, which is unusual for a football club. Commercial income was up 15%, how much, if any, of this is due to deals signed with Fosun related companies is unknown.

Some clubs in the Championship generate up to 85% of their income from broadcasting, mainly due to the receipt of parachute payments.

Costs

The main costs at a football club are player related, wages and transfer fee amortisation.

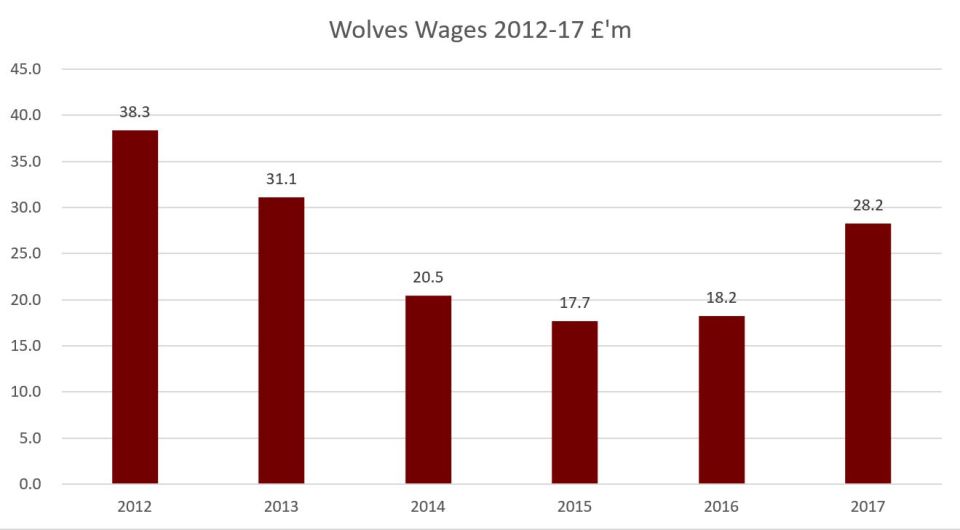

Wolves wages almost halved from 2012 to 2014 as the club fell from the Premier League to the League One. Whilst this was tough to take for fans, it did allow the club to jettison some deadwood during that period, such as Jamie O’Hara, who was allegedly being paid a seven figure sum a year whilst playing for the club’s reserves in League One, a situation that troubled him so much he was forced to have affairs with random women whilst his former Miss England Danielle Lloyd was taking the bins out at home.

For the first two seasons back in the Championship Wolves showed restraint in terms of wage spending. The arrival of Fosun and Mendes resulted in wages increasing by 55% last season.

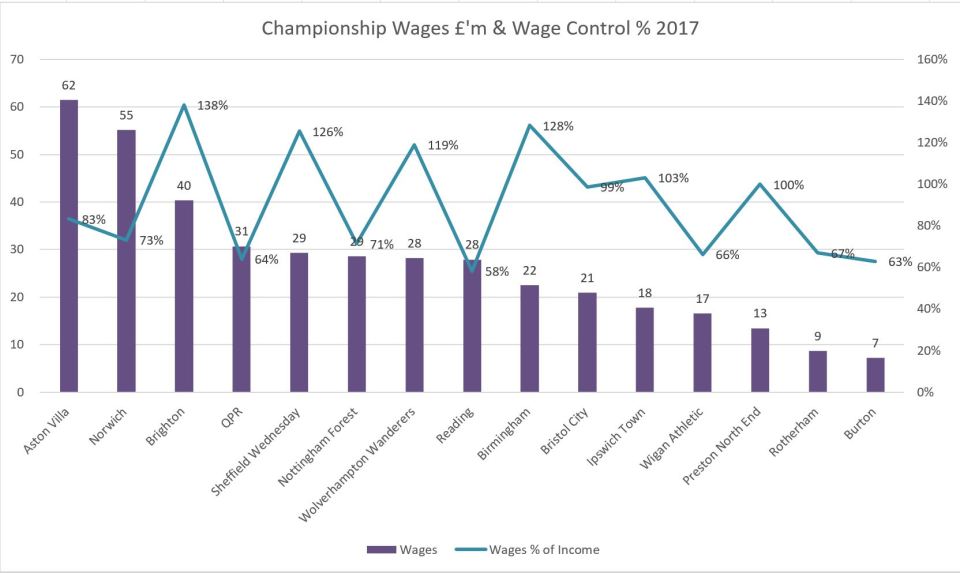

Whilst there are many sniping at Wolves for this increased wage expenditure, the club is only marginally ahead of the average for the division of

Wages fell by a quarter but are still reasonably high by Championship standards, where the average for last season was about £27.3 million. Clubs such as Sheffield Wednesday, Brighton and Forest, all of whom also do not receive parachute payments, paid out higher sums for wages last season.

Amortisation is how clubs deal with transfer fees in the profit and loss account. When a player signs for a club the transfer fee is spread over the life of the contract. Therefore, when Wolves signed Ivan Cavaleiro for £7 million from Monaco at the start of the season, but as he signed a five year contract the amortisation charge of £1.4 million a year for five years (£7m/5).

Wolves total amortisation charge was £7.6 million, 160% higher than the previous season, and higher than any other club not in receipt of parachute payments. It was still only a third of the amortisation of Villa though, who spend over £80 million on new players in 2016/17.

Putting these two costs together highlights how much of a transformation arose in 2016/17. The previous season the club’s combined wages and amortisation cost represented £78 for every £100 of income, in 2016/17 this nearly doubled to £151 for every £100 of income.

With the investment in new players in 2017/18, this ratio is likely to increase further in 2017/18. It does suggest that Wolves are going for broke this season, which may mean that they would have to cut back substantially if promotion is not achieved, although their present lead over the team in third place is looking substantial.

Losses

Losses are income less costs. The bad news for Wolves is that the club lost a lot of money last. The good news is that profits were made in previous years, which will help the club in terms of FFP compliance.

Operating losses are the trading losses of a club, and they exclude interest costs. In 2016/17 this worked out as £22.6 million, which works out as £430,000 a week.

It is these losses, and the subsequent purchasing of players for whom Mendes is the agent in 2017/18, that has caused so much grumbling from other chairmen in the Championship.

Such grumbles weren’t heard however when Wolves made far larger losses in 2012/13, although this could be that they finished bottom of the Championship that season and stank out the division.

Under FFP rules, Wolves can make a maximum FFP loss of £39 million over three years in the Championship. Wolves have an overall loss of £12.6 million over the three year period, so appear to be significantly within the limit. However, if losses are similar this season to 2017 then the three year total will rise to about £38 million. Add in interest costs on borrowings and the losses are likely to exceed £39 million.

Fortunately, some costs, such as infrastructure, academy and community schemes, are excluded from the FFP calculations. Wolves have a category one academy, which costs about £5 million a year to run, so this, combined with other allowable costs, should ensure the club has some leeway in terms of meeting the FFP target.

Player trading

The accountants treat player trading in a weird way in the accounts. We’ve already shown that when a player is signed, his transfer fee is spread over the life of the contract. When the player is sold, the profit is shown immediately, and it based on the player’s accounting value, not the original transfer fee.

This creates erratic and volatile figures in the profit and loss account.

If we instead focus on the actual purchase and sales, the following arises

After three years of effective restraint, the arrival of new owners Fosun resulted in Wolves spending like drunk lottery winners in 2016/17. The club spent over £32 million on new players in 2016/17. In addition to this, hidden away in the footnotes to the accounts is revealed that the club spent a further £35 million in the present season.

This is likely to substantially increase the wage and amortisation charge, but Wolves will be able to offset against these costs the £7.3 million of profits on player sales, so should be within FFP limits.

Debt

Fosun lent Wolves £21 million in 2016/17, but unlike the owners at West Ham, who have charged over £14 million in interest charges since acquiring the club, the loans are presently interest free.

It is likely that Fosun have lent further sums during the present season.

In addition to loans from the owners, whilst Wolves have spent a fortune on new players, most of this has been on credit.

Wolves owed other clubs £23 million for player transfers at the end of the 2017 season, this is likely to be substantially higher at the end of the present season.

Summary

Wolves have been transformed financially following their takeover by Fosun. However, having cash to spend is one thing, and spending it well is another.

Fosun are worth £13 billion, so there is plenty of spare money to spend should they reach the Premier League. What is slightly concerning is the set up of hte group, with Wolves now being owned by a Fosun subsidiary based in the British Virgin Isles.

Last season, whilst there were big money signings, they didn’t have a positive impact on the league position. It looks as is that problem has been remedied for 2017/18.

The role of Jorge Mendes is intriguing, although one would wonder why someone who already represents Cristiano Ronaldo and Jose Mourinho needs to spent a lot of time in relation to having a significant involvement with a Championship club, as the snipers claim.

FFP will be an issue, but only if the club fails to be promoted to the Premier League this season. The club is likely to be within the limits for the three seasons ended 2017/18 if our calculations are correct.

Data Set