Sunderland: Short Changed

As Sunderland’s new owner Stewart Donald picks up the reigns of the club and former head honcho Ellis Short walks away with the debts of £161 milion (and £40m in instalments from Donald) , the figures for their final season in the Premier League contain some grim reading although are rescued to a degree by the sale of Jordan Pickford in June 2017.

Summary of key figures (Sunderland Limited)

Income £126.4 million (up 17%)

Broadcasting income £95.6 million (up 34%)

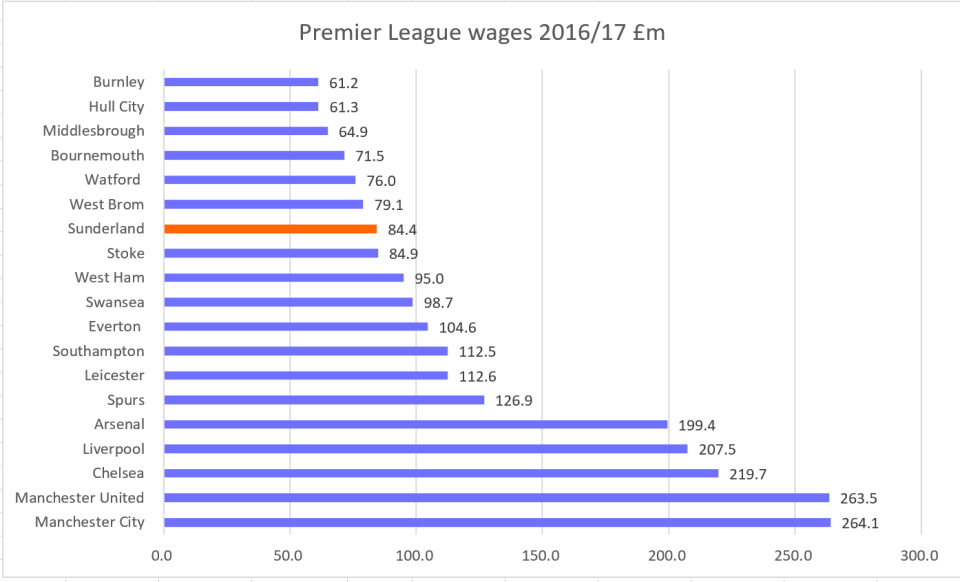

Wages £84.4 million (up 1%)

Loss before player sales £38.9 million (up 30%)

Player purchases £47.5 million (£30.7 million in 2016)

Player sales £43.1 million (£11.7 million in 2016)

Borrowings: £161.7 million (£137.3 million in 2016)

Income

The Black Cats have been in the Premier League (PL) since 2007, and Ellis Short took control of the club a year later.

Their income has broadly been linked to new PL broadcasting deals, which are negotiated every three years.

The impact of the new TV deals that commenced in 2011, 2014 and 2017 have been the biggest drivers of extra income for the club.

The problem for a club such as Sunderland is trying to find other ways of generating income when there is so much focus on the self-styled ‘Big Six’ (United, City, Liverpool, Chelsea, Arsenal and Spurs).

During their ten years in the Premier League, Sunderland earned £866 million, their fans will wonder how well that money has been spent.

Nineteen clubs who were in the Premier League last season have reported their results to date. Only small London club Crystal Palace, whose owner also controls a company called ‘Smoke and Mirrors Limited’ are now outstanding in sending in their results to Companies House, although they have sent them to the Premier League as the figures have to be scrutinised by the end of the calendar year.

All Premier League clubs are reporting higher income for 2016/17 than in the previous season. The average income of the 19 clubs that have reported to date is £233 million, up 28% from £182 million the previous season. The average in the Championship is just £28.6 million.

The median income, (remember that from your GCSE Maths class?) perhaps more relevant to a non-Big Six club, is £171 million.

Sunderland are in a bunch of nine clubs who are in the £117-138 million income bracket.

The main reason for the increase in overall income in the Premier League for 2016/17 was the new Sky/BT domestic TV deal, worth £5.1 billion over three seasons.

Overall the Big Six already have 56% of the total income of the Premier League clubs but want more.

Like all clubs Sunderland broadly their income from three sources, matchday, broadcasting and commercial/sponsorship.

Matchday Income

Matchday income fell by 15% to £9 million. Whilst stated attendances fell only 4% to an impressive sounding 41,287, anecdotal evidence was that many fans, especially those with season tickets, did not go to many matches, such was the dismal performances on the pitch.

Sunderland’s matchday income per fan fell by over 10% to just £217. This works out at just £11.41 per match and is one of the lowest in the division. For Sunderland fans querying the figure remember this is the average price so included children and other concessions and is also net of VAT at 20%.

Part of the reason why the figure is so low is that Sunderland is not an affluent city and does not attract large numbers of football tourists who are willing to pay large sums to attend matches (and spend a lot on merchandise).

Being knocked out of the FA Cup in the third round didn’t help matchday income either.

The lack of decent football had a more significant impact on the prawn sandwich brigade, as it’s very difficult to sell boxes and hospitality packages at high prices to watch poor football.

Under Ellis Short, Sunderland’s matchday income fell by over a third during the nine years he oversaw the club. He can’t be accused of fleecing the fans, as overall in the Premier League, matchday income counts for £1 in every £7, but for Sunderland it is only £1 in every £14.

The large capacity of the Stadium of Light meant that Sunderland did have greater matchday income than nearly half the clubs in the Premier League last season, but their total pales into significance compared to the big boys.

Care should also be taken when looking at individual figures, as different clubs calculate numbers in different ways. Some clubs include merchandise sales as part of matchday, whereas others stick it into the commercial heading.

Overall the Big Six hoover up 75% of matchday income of the Premier League, as they have larger stadia in the main and also are able to attract daytrippers and tourists to watch their matches, at premium prices.

Broadcast Income

Broadcast income for Premier League clubs is linked to deals signed by the PL on behalf of all 20 clubs in the League.

Sunderland suffered in 2016/17 from finishing bottom of the table compared to a squeaky bum 17th the previous season. This was more than compensated though by the new domestic BT/Sky broadcasting deal, which was worth 70% more than the previous one that expired in 2015/16.

Premier League TV money is divided into 5 pots, as follows:

For domestic rights there are three pots.

- 50% of the money is split evenly between all 20 clubs (called the ‘Basic Award’)

- 25% is split based on the number of times a club appears live on TV, with each club being guaranteed ten matches, and an extra £1 million for each additional appearance

- 25% is based on final league position, with the bottom team receiving £1.9 million, and every place above that being worth an additional £1.9 million. Therefore, by finishing four places higher in 2016/17 than the previous season Sunderland earned an additional £7.6 million, which is more than they earned through matchday income.

Overseas TV rights are presently split equally between all 20 clubs, but a bunfight is likely to take place this summer as the ‘Big Six’ claim they are main reason why overseas broadcasters pay so much for PL rights. The Big Six’s argument conveniently ignores that they earn additional broadcasting rights from appearing in European competitions.

If the Big Six are to be successful, they will need 14 votes at the meeting of club owners in the summer. Expect to see tantrums and threats of joining/creating a European Super League should they not get their way. They are of course more than welcome to close the door should they leave.

The PL’s central advertising/commercial contracts are also split evenly between all 20 clubs.

Despite stinking out the Premier League in 2016/17, Sunderland’s broadcast income increased by a third to nearly £96 million. In the three previous season the figure was broadly static, reflecting the Sky/BT deal that was in operation during that period.

It comes as no surprise that Sunderland were close to the bottom of the table in terms of broadcast income for the season, given that they only received £1.9 million in prize money for finishing 20th in the PL.

The relatively democratic division of broadcast income is highlighted in the above table. For every £1 of TV income received by Sunderland, the top earning team (ere Manchester City) earned £213. When it comes to matchday income that figure rises to £580 earned by Manchester United for every £100 by Sunderland, and commercial is £999 by United for every £100 by Sunderland.

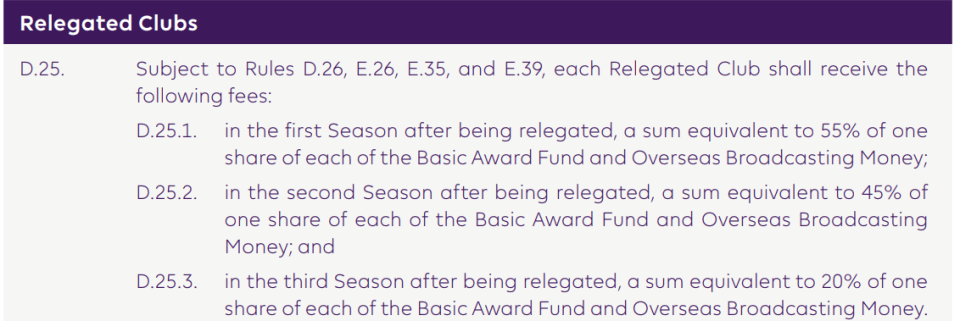

As the club was relegated in 2016/17 attention now turns to the PL’s snappily named rule D.25, more commonly called parachute payments.

Sunderland therefore will have received for 2017/18 55% of the basic award (£35.3 million in 2016/17) and overseas broadcasting money (£39.1 million in 2016/17), which works out at £41 million.

For the forthcoming season in League One, this will drop to £33.5 million, and then there will be a final payment of £14.9 million in 2019/20.

After that the club’s broadcast earnings will be governed by the EFL broadcast deal, which is worth about £2.3 million a season for clubs in the Championship, £345,000 in League One and £230,000 in League Two.

In addition, clubs in the EFL receive solidarity payments from the PL. Here a proportion of the PL’s broadcast deal is passed down to the 72, and this is worth about £4.3 million for a Championship club.

Commercial Income

Commercial income in the Premier League is a case of the haves and the have nots. Here the Big Six mop are to an extent able to name their price, as it is a seller’s market and the likes of Liverpool exploit their global appeal by signing deals for individual products and end up having an official…err…timing partner with watch manufacturer Holler.

For clubs such as Sunderland the outlook is different. Here the buyers can play the likes of The Black Cats, Bournemouth, Everton, Stoke etc. off against each other when negotiating shirt and commercial deals, so the prices are far lower. In addition, smaller clubs have limited overseas appeal as football tourists and other plastic fans only tend to ‘support’ the major clubs. There are relatively few fans in Malaysia and Lagos who support the non-Big Six clubs.

Sunderland split out their hospitality/conference income out in the accounts, unlike most clubs.

Sunderland’s catering income fell by 30% in 2016/17, mainly due to some season ticket holders becoming so disillusioned that they did not turn up to matches, and the club struggling to sell hospitality packages in respect of a team that only won three games at home all season. Commercial income fell too, Dafabet continued their shirt sponsorship, worth about £5 million, but the club struggled with other deals.

Cost

The main costs at a football club are player related, wages and transfer fee amortisation.

Wages

During the Ellis Short era, Sunderland paid out £600 million in wages in nine seasons. Both he and Sunderland’s fans must be scratching their heads over just how well that money has been spent, although fans will still probably have nightmares at the memories of the likes of Santiago Vergini, Jozy Altidore and Danny Graham taking home large sums each week.

Wages increased during the Short era in all but one season. Although the total wage bill only increased by 1% in 2016/17, Sunderland have a financial year end of 31 July. This means that for some players relegations clauses would have kicked in on 1 July as at that date the club is officially no longer a member of the Premier League.

Sunderland’s accounts therefore suggest the average wage was (we estimate) about £40,500 a week, although that includes one month at the lower rate in the Championship.

Their total wage bill is broadly where you would expect it to be for a club that has been a constant feature of the Premier League for the last decade, above that of promoted clubs and below that of clubs with bigger stadia and resources.

The riches of the Premier League TV deal meant that Sunderland only paid out £67 in wages for every £100 of income. If the club is relegated to the Championship the outlook is different. In the last season for which there are full records clubs paid out an average of £101 for every £100 in wages, which leaves nothing to pay for the other other running costs…including player signings.

One reason why Sunderland’s wages to income ratio has fallen is due to a variant of Financial Fair Play (FFP) called Short Term Cost Control (STCC). This restricts wage growth to £7 million a season plus any money the club generates itself from matchday and commercial sales. For a club such as Sunderland this gives a significant challenge, especially with matchday and commercial income declining.

Ellis Short has always been a hands-off owner and has tended to delegate the day to day running of the club to a chief executive. This person has been very well paid, although the competence of the decision making must surely be questioned given the many crises the club has encountered during that period.

Running a company that is effectively only open for business 20-25 times a year should allow the chief exec to concentrate on operational issues, but Sunderland seem to have had too many embarrassing moments that call into question the culture of the club, which should be set at boardroom level and filter down via the manager and coaching staff.

Chief executive Martin Bain is presumably the lucky recipient of the £1.24 million package for the highest paid director of the club for 2016/17, although it is suspected he will be packing his bags (with a large payoff) should the club sale proceed shortly.

Sunderland have had three big payoffs under Ellis Short for directors who left the club rapidly and were given ‘compensation for loss of office’. In 2011 someone (probably CEO Steve Walton) received a £573,000 payoff, the following year it was an eye watering £1,996,000 (probably to Niall Quinn) and in 2016 Margaret Byrne, who oversaw the Adam Johnson incident was rewarded to the tune of £850,000.

Player amortisation

Transfer amortisation is the method used to expense transfer fees in the profit and loss account. When a player signs for a club the transfer fee is spread over the life of the contract. Therefore, when Sunderland signed Didier Ndong for £13.6 million from Lorient on a 5-year contract, the amortisation charge works out as £2.72 million a year (£13.6/5).

The total amortisation expense in the profit and loss account of £29.4 million for 2016/17 is the sum of all the players who have been signed by Sunderland and for whom there has been a transfer fee.

Sunderland’s amortisation total of £29.4 million is marginally lower than the previous season, but over the last few years has been reasonably consistent. The advantage of looking at amortisation instead of player signings and sales for an individual season is that it removes the fluctuations that can arise on a short-term basis.

Whilst they are not operating in the stratospheric levels of the Big Six, Sunderland had a reasonably high amortisation cost in 2016/17 compared to the other 14 clubs who are in the relegation shakedown at the start of each season.

This would appear to suggest that Sunderland’s managers have been backed in the transfer market by the owner, but whoever oversees recruitment has wasted the budget.

If wages and amortisation costs are added together, then they took up 90% of Sunderland’s income in 2016/17, and this was the lowest figure for this ratio during Short’s ownership period.

Over his nine years in charge of the club in the Premier League, it had total income of £803 million, but had wage and amortisation costs of £833 million, which means that Ellis Short was responsible for all the remaining costs of running the club.

The first signs of how relegation is affecting local people who work for the club is shown in terms of staff numbers, as these fell by 10% in 2016/17. It is highly likely that this decline will accelerate in 2018 as the club was once again relegated, and this is the real tragedy in relation to the club. Footballers are transient in nature and moving from club to club is an occupational hazard, but for the people employed behind the scenes, they tend to be often supporters whose job at the club pays their day to day bills.

Sunderland also had a couple of one off costs in 2016/17. They were forced to pay £9.7 million in a disputed court case with Inter over the signing of unwanted Ricky Alvarez, who was signed on loan with a clause that Sunderland had to buy him in 2016 if they avoided relegation. The club duly did this, but didn’t offer Alvarez a new contract, so he disappeared to Sampdoria, and Sunderland effectively had to pay £1.2 million per game for his eight- match career at the Stadium of Light for his transfer fee, plus his wages.

Following relegation, Sunderland then valued the players in the squad using their best estimate of market values. They then wrote off over £14 million from the accounting values of the players, which is a huge sum given the way that players are accounted for in the books.

The club have not given the names and amounts by which they have written down individual players, but Mackem fans will no doubt have a long list of the guilty parties.

Loan Interest

Sunderland have considerable debts. Ellis Short’s loans are thankfully interest free. The club also has a £70 million loan from American lender SBC. This loan attracted an 8.5% interest rate, which meant that an interest charge of £6.5 million clocked up on the loan in the year, and along with other borrowing costs, the club was charged £130,000 a week in interest over the season.

Profits and losses

Profits are income less costs. Sunderland made losses before player sales in 2016/17 of £38.9 million, which works out as £750,000 a week. Even if the one-off costs discussed above are eliminated, the loss falls to a still substantial £14.8 million.

Under Ellis Short Sunderland lost a total of £248 million before player sales, and this is the richest division in the world.

EBIT (Earnings before interest and tax) remove volatile one-off transactions such as legal issues on disputes, player sale profits and payoffs.

In the Premier League Sunderland had the fifth highest EBIT loss.

Profits on player sales are calculated in a complicated manner. Rather than compare the sale and purchase price for the player, instead the sale fee is compared to the accounting value of the player, which is the cost less any amortisation charges. Sunderland sold Jordan Pickford came through the youth team, and so the whole fee is treated as a profit.

This allowed Sunderland to show a profit of over £33 million on player sales for the year to 31 July 2017. This is however lower than many of the clubs around them who made an EBIT loss. Chelsea, for example, sold Oscar to China for about £60 million, and showed a total profit on player sales of £69 million.

If profits on player sales are added in, Sunderland’s losses fall to £6 million. They are however the only club to make a loss after player sales in the whole of the Premier League.

Sunderland showed a profit of are the only club in the Premier League last season to make a loss before player sales last season, which again is an indictment of how poorly the club has been managed.

After a long period of time in which nearly all clubs were loss making, partially due to Alan Sugar’s ‘prune juice’ effect, where any increases in TV income went straight through the club into player wages, the Premier League is now far more lucrative.

Under Financial Fair Play (FFP) rules, Premier League clubs can make a maximum FFP loss of £105 million over three years. In the Championship it is £39 million over three years.

So, for the season that has just ended Sunderland will be allowed an FFP loss of two years in the Premier League plus one in the Championship, which gives a figure of £83 million. Some costs, such as infrastructure, academy and community schemes, are ignored for FFP purposes, so the club should be relatively safe in respect of FFP compliance.

Player trading

Accounting for player trading is troublesome. We’ve already shown that when a player is signed, his transfer fee is spread over the life of the contract. However, when the player is sold, the profit, which is based on the player’s accounting rather than market value, is shown immediately in the profit and loss account.

This creates erratic and volatile figures in the profit and loss account, which is why these are separated out from the rest of the financial results.

If we instead focus on the actual purchase and sales, Sunderland have the following figures:

The above table shows that over the nine years under Ellis Short’s ownership Sunderland have bought players for £329 million and generated sales of £169 million, a net cost over the period of £160 million over the period.

At the start of 2016/17 the squad had cost a total of over £109 million, so money had been invested in the players, but it included an awful lot of duffers.

Sunderland’s spending in 2016/17 was competitive by the standards of clubs who are not part of the PL elite. It reinforces the view that signing rubbish players, rather than not backing the manager in the market, was the driving force behind the club’s relegation to the Championship.

Debts to and from the club

Whilst Sunderland sold Pickford in June 2017, it appears that Everton paid a fair amount of the fee in cash, as amounts due from other clubs were only £11.4 million.

Of greater concern is the fact that the club owed other clubs £45.2 million for player transfers. This may be insignificant compared to the likes of Manchester United who owe over £180 million, but United do have huge income streams and don’t have league games at Fleetwood and Plymouth next season.

Some of these borrowings have been converted into shares, but at 31 July 2017 Short was owed £93 million via his Jersey based company Drumaville, and a further £70 million is due to SBC.

These loans are secured, which officially means that should repayment be sought (and the SBC loan is officially due for repayment in August 2019) the lenders could force the sale of the Stadium of Light and training facilities.

When the takeover of the club by Stewart Donald’s consortium was announced, Ellis Short inferred he was leaving Sunderland debt free, effectively writing off his loan and taking on the responsibility for the one from SBC.

What is uncertain in respect of the takeover is whether the consortium is paying anything for the shares, and if there are sums due to Short should the club return to the Premier League soon.

Summary

Ellis Short’s tenure as Sunderland owner is a textbook example of someone who thought the Premier League was an opportunity to make a lot of money and getting it spectacularly wrong.

He has effectively written out a cheque for half a million pounds every week for ten years to keep the club afloat, and during that period has seen a series of executives and managers come and go at the club.

Whilst he can afford to lose this sum, it’s still an unpleasant experience for anyone to walk away from such a spectacular financial mess.

The reaction of Sunderland fans seems to be measured. They appreciate Short’s benevolence but are angry at the quality of decisions made by a series of well remunerated professional business managers in charge of club operations.

The irony is, having measured the club value using the industry standard Markham Multivariate Model, Sunderland as a Premier League club was worth about £215 million if managed correctly, but as a Championship, and now a League One club, it is effectively worthless, as the losses each week and lack of TV income is too much of a burden.

The new owners are taking on either a black cat…or a white elephant.

Data Set

One Comment

Pingback: