Derby County 2017/18: Say You’ll Be There

Making sense of Derby County’s 2018 accounts is a challenging task as the club’s structure has been changed nearly as often as the line-up of the Sugababes.

Enigmatic is the politest word that could be used to describe way that a myriad of different companies that are now running different elements of Derby which was further complicated by a new holding company Gelaw NewCo 203, taking over on 28 June 2018.

Legally such a structure is perfectly valid and is common in other industries, whereas previously all of the club’s activities went through Derby County Football Club Limited the new set up arose after Mel Morris CBE took control of the club.

Income

Matchday, broadcast and commercial income are the three standard income categories used to comply with EFL League recommendations.

Obviously, clubs recently relegated from the Premier League have parachute payments too to increase their income and research indicates this is worth about seven extra points in the first season back in the Championship.

Runs in the cup that are televised and live appearances on Sky can increase the broadcast income slightly, with payments of £100-£140,000 for home Championship matches (and £10,000 for away matches).

Relative to other non-parachute payment receiving club Derby do fairly well as they have generated decent TV audiences, but the extra sums received are miniscule compared to those clubs recently relegated.

Income for clubs in the Championship from matchday is (number of matches x average price per ticket x average attendance) so with a ground that is practically sold out every home match there’s not a lot of scope to increase revenues unless prices go up.

Sponsorship and commercial income are an area where there is growth potential but there are 23 other clubs in the Championship also competing in this area but Derby have done well by divisional standards.

Some cynical fans might take the view that the big increase in commercial and hospitality income that commenced in 2017 may have come from companies related to Mel Morris CBE but there’s no evidence to support this theory although seeing with the fourth highest commercial income in that division and also earn more than quite a few Premier League clubs too does cause eyebrows to raise.

For a club the size of Derby to have the second highest non-parachute payment income in the division is an achievement, and surprising that they’ve outperformed the likes of Villa and Wolves in this regard too.

A breakdown of Derby’s overall income shows a fairly even split between the sources. Some clubs in the Premier League have nearly 90% of their income from broadcasting.

Costs

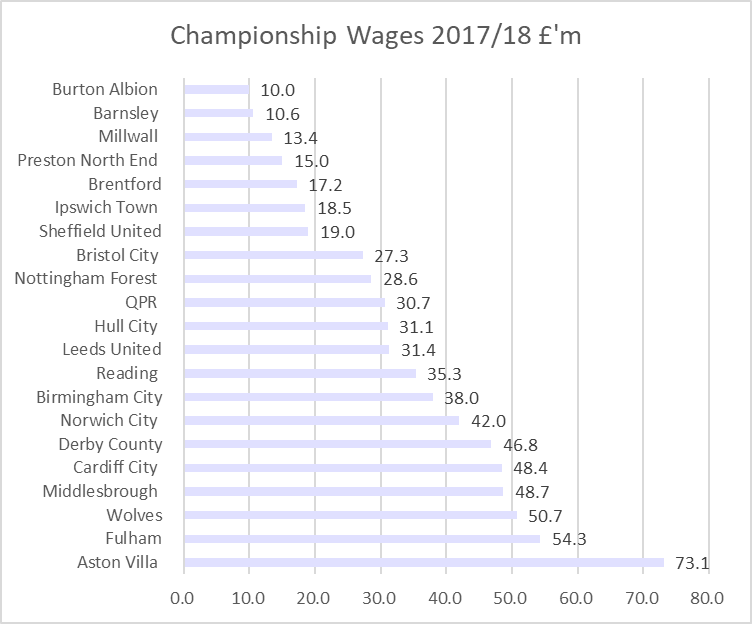

Very many fans get angry when the subject of players’ earnings are discussed, and Derby’s wage bill seems to have taken a big jump in 2017/18.

Overall wages for parent SevCo 5112 were nearly £47 million, an effective increase of 18% (SevCo’s actual wages for 2016/17 were £33.1 million but only covered a period of 10 months instead of 12) which meant that wages were £157 for every £100 of income, part of the increase could be attributed to commercial staff numbers increasing by 39 but the majority relates to players.

Unless players receive a competitive wage, they’re likely to go elsewhere and as owners and fans want promotion so clubs such as Derby with no parachute payments have to pay accordingly.

Relative to clubs in receipt of parachute payment Derby were not far behind other clubs last season (apart from Villa) but were high payers compared to other clubs, especially if the promotion bonuses paid to Fulham, Wolves and Cardiff are stripped out.

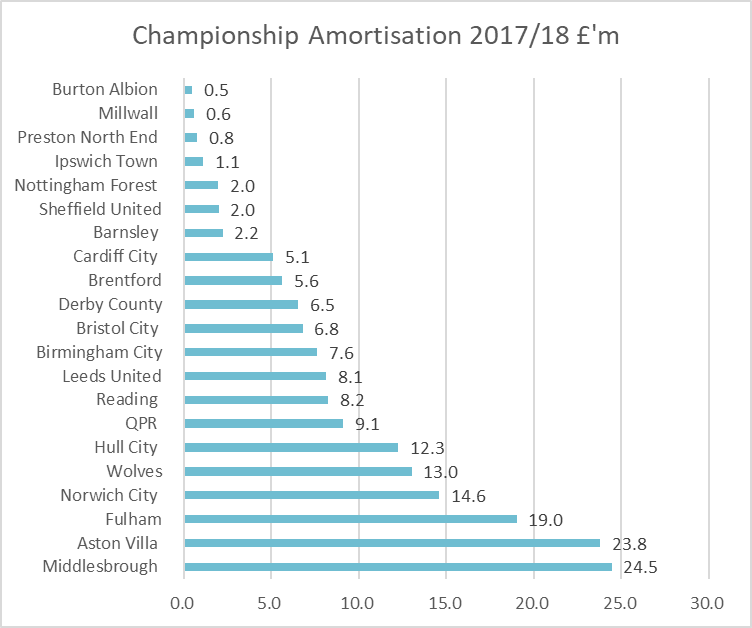

In terms of transfer fees, these are spread over the life of the contracts signed by players in what are referred to as amortisation costs.

Tom Lawrence cost Derby an estimated £5 million when he signed from Leicester in August 2017 on a five-year deal, so that would normally work out at £1 million (£5m/5) a year in amortisation costs.

Experienced Rams’ fans may know that their club is unique in the way it treats amortisation though which has the effect of reducing the expense in the accounts in what is best known as ‘Melenomics’ and no other clubs in England use such an approach.

Spreading the cost of transfers the ‘Derby Way’ resulted in the club being sandwiched between Brentford and Bristol City in the Championship amortisation table for last season which seems very low given that Derby’s wage bill is the same as both clubs combined.

Putting wages and amortisation together gives a total cost of £53.3 million which vastly exceeds revenues of £29.1 million, Derby had an expense of £183 in this area for every £100 of revenue but this was still far from the highest in the Championship last season.

Identifying the other costs incurred by the club is tricky as they are grouped together as ‘other costs and these increased by , depreciation increased by £1 million, rents paid doubled to £325,000 but ‘other costs’ overall increased alarmingly to nearly £19 million with no explanation in the accounts.

Costs therefore totalled £76 million which led to the sale of Pride Park to another part of Mel Morris CBE’s business empire which generated a profit of £40 million in order to ensure the club did not breach Profitability and Sustainability (FFP) limits and risk sanctions such as the points deduction suffered by Birmingham City.

Exceptional transactions such as the sale of the stadium appear to blow a hole in the principles of FFP but if allowed by the EFL as the club seems to imply then fans needn’t worry too much.

Getting away with such behaviour (and it looks as if Sheffield Wednesday may have done similar with Hillsborough) gives further support to the view that the only winners from FFP are the creative accountants and slippery lawyers who devise such transactions.

Profit

In the press release on the Derby website it said the club had made a profit of £14.8 million, but this applies to Derby County Football Club Limited and conveniently ignores the costs incurred by the commercial department, academy and stadium running costs which form the other subsidiaries of SevCo 5112.

Reading the SevCo 5112 accounts is more depressing as there was an operating loss, which represents revenue less day to day running costs, of £46.8 million.

Losses before disposals for the Championship total over half a billion pounds for 2017/18 and that is excluding results from Sunderland, Sheffield Wednesday and Bolton as many clubs gamble on being one of the three teams that win the golden ticket to the Premier League.

Incurring losses of this magnitude means that clubs are reliant on asset sales (usually players) and owner investment to cover the losses.

Stripping out costs such as amortisation and depreciation (depreciation is the same as amortisation except this is how a club expenses other long-term asset such as office equipment and properties over time) then another profit figure called EBITDA (Earnings Before Income Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation) is created. This is liked by professional analysts as it is the nearest thing to a cash profit figure.

Making cash losses of over £700,000 a week last season explains why Derby needed to sell Pride Park although selling it back to Mel Morris CBE is equivalent of transferring money you already have from the left hand to the right hand.

EFL rules allow clubs to lose £39 million over three seasons, but some costs (infrastructure, academy, women’s football and community schemes) are excluded from the FFP calculations.

Losses for Profitability & Sustainability purposes were, based on our calculations, £53 million over the three years, which, based on the publication of the Birmingham City ruling, equivalent to an eleven point deduction.

Chopping eleven points off Derby’s total for this season would have sent the club spiralling out of contention for a playoff scheme, so whoever came up with the idea of the sale and leaseback of Pride Park should perhaps win the player of the season award.

Other clubs such as Villa, Sheffield Wednesday, Reading and potentially Birmingham have followed the Derby approach but not have sold their stadia for as high a price.

Bringing the stadium sale into consideration doesn’t just ensure that Derby have complied with the P&S rules, it also means that if the club is not promoted this season it should be able to compete in the summer transfer market as the cumulative P&S total shows a substantial profit.

EFL critics will be up in arms if this type of transaction is allowed, but it is the club owners who vote for the rules, they are not imposed by the league itself independently.

One consequence of the sale and leaseback deal is that it looks as if Derby will be paying rent of about £1.1 million a year for the use of the stadium.

Player Trading

Derby spent £15 million on new signings in 2017/18 on Lawrence, Wisdom, Huddlestone and Jerome and had sales of £4.3 million mainly in relation to Cyrus Christie. The sales of Will Hughes and Tom Ince which took place in the summer of 2017 were included in the accounts for the year ended 30 June 2017.

The large spend on players is why the amortisation charge in the profit and loss account is so high. Fans often point out that clubs also sell players and that net spend is a better measure of a club’s investment in talent.

Mel Morris CBE’s commitment to getting the club promoted is evident from the above graph as prior to that Derby were not serious players in the Championship transfer market.

The total cost of Derby’s squad at 30 June 2018 was £62 million which puts the club at the top end of the division which again puts it at odds with the relatively low amortisation charge.

Funding

Clubs can obtain funding in three ways, bank lending, owner loans (which may be interest free) or issuing shares to investors. Mel Morris CBE had put over £95 million into Derby in 2016 and 2017, his approach for 2017/18 came in the form of the stadium purchase for £81 million.

Summary

Derby went for broke in 2017/18 in trying to achieve promotion to the Premier League. To achieve this the club had to indulge in some eyebrow raising accounting transactions which appear to be at odds with the spirit, if not the letter, of P&S rules.

Promotion this season will be great for fans, but the legacy of the stadium sale income should ensure that even if the club doesn’t go up then Frank Lampard still has some leeway in recruiting players this summer and there is no need for a fire sale.

Incurring losses of this magnitude means that clubs are reliant on asset sales (usually players) and owner investment to cover the losses and Derby took an unusual approach here.

Relying on owners to keep putting money into clubs, especially when so many are abused by some financially illiterate fans for ‘lacking ambition’ does increase the risk of clubs going into administration or worse if the owner decides they have had enough grief.

Letting players go does generate cash but also has a detrimental impact on the quality of the remaining squad but is a financial necessity at times as was seen in 2016/17 when Derby sold Ince, Hughes and Hendrick to generate over £16 million profit.

If the EFL is going to allow owners to sell stadia to themselves to comply with P&S, then it would make sense the rules to be scrapped. At present the nature of the rules simply results in very expensive accountants and lawyers to devise schemes and fans would rather money be spent on the game instead of school fees and Ranger Rovers for bean counters.