West Ham 2018/19: Flares’n’Slippers

In January 2020 David Sullivan, West Ham’s controlling shareholder said “Overall, I believe the club’s in a far better state than 10 years ago” so we thought we’d put that to the test with a look at the club’s finances during that period.

Decade of success or standing still? The West Ham that Sullivan and Gold acquired from the former Icelandic Bank owners was certainly in crisis, but have their efforts improved the happiness of fans who now attend the rented London Stadium?

Rebelling fans know West Ham have just announced their accounts for the year ended 30 June 2019, and like events on the pitch last season, disappoint more than excite.

Income

A Football club generates income from three main sources, matchday, commercial and broadcasting.

The matchday income for West Ham in 2018/19 was £27.1 million, which is just £200,000 more than the club’s final season at the Boleyn, and £7 million more than most of the preceding seasons.

Having this amount of matchday income puts West Ham 7th in the Premier League, but a long way behind the ‘Big Six’ that fans thought the club would be challenging when they said farewell to their spiritual and cultural home in 2016.

Every club generates matchday income by (number of matches x average price per ticket x average attendance) and here despite big attendances West Ham are ahead of the provincial clubs but behind the elite.

Relatively low prices at the London Stadium, which has a traditional old school working class fanbase, coupled with fewer matches than those clubs playing in UEFA competitions, meant that West Ham generated only 28 pence per seat for every £1 that Chelsea made last season.

Being tenants at the London Stadium also means that West Ham can effectively only make cash from the stadium for 19 days a season (plus any home cup matches) whereas Spurs can sweat their asset in the form of the new stadium with NFL matches, conferences, catering and concerts.

Every club has a season ticket price policy and West Ham, to their credit, seem to have some available at £299 (£320 for 2019/20) but for some matchdays the cheapest adult tickets are £55 each, which doesn’t include the binoculars needed to see the pitch from these vantage points.

Being able to exploit the modern facilities of the new stadium for commercial gain was another justification for the move in 2016, and this appears to have some merit.

A look at the commercial income totals shows that West Ham have doubled this revenue source over the last decade, with a noticeable jump since moving to the new stadium in 2016/17.

Commercial income follows that of matchday in that West Ham are again ‘best of the rest’ (Everton’s should be treated with caution following their deals with Putin pal Alisher Usmanov) but still far behind the elite.

Keeping up with the Big Six of the Premier League is unrealistic for West Ham unless they can offer sponsors UEFA competition exposure or the attraction of players that have huge social media followings.

A look at Broadcasting income shows a similar story, with West Ham recoding record figures that look good compared to the club’s history, but pale into insignificance when matched against the peer group they want to challenge.

The increase in broadcast income was mainly due to West Ham finishing 10th last season compared to 13th in 2017/18, as each additional place is worth just under £2 million.

The importance of qualifying for European competition is evident from the above table which shows the benefits to the elite clubs for reaching the latter stages of the Champions and Europa League, which can be worth up to an extra £100 million in prize money plus additional gate receipts and sponsor add-ons.

Having European qualification would change things for West Ham but realistically they would have to be regular participants there before competing in the same pond as the ‘Big Six’.

Even if the club did make it to the Europa League, they are now competing for places with Everton, Wolves and Leicester domestically, all of whom have owners who are keen to pour more money into their clubs to secure higher places in the table.

Broadcasting income growth has fallen domestically for the three years starting 2019/20 but the rise in the international rights has offset that, realistically there is limited future growth in traditional TV rights.

Overall West Ham are stuck against the glass ceiling in terms of being the 7th biggest revenue generators in the Premier League but still only earning half of that of Arsenal, the next club in the earnings league.

Costs

Like it or lump it, player related expenses are the highest element of a club’s cost base and generate endless discussion from fans and the media.

Every club needs to pay competitive wages to attract talent, resulting in what Sir Alan Sugar calls the ‘prune juice’ effect of additional money coming into the top of the game quickly exiting at the bottom in the form of player wages and transfer costs.

Year on year in 2018/19 wages increased by over 27% to an average weekly sum of £63,000 for first team regulars.

No one will be surprised that West Ham have the 8th biggest wage bill as they have the 7th biggest income stream, what will disillusion fans is the failure to make more progress on the pitch given that the unpopular owners have invested money on the pitch, albeit poorly.

The concern with the wage bill is that West Ham spent £71 on this for every £100 of income, UEFA recommend keeping this to no more than £70 so realistically the club have limited wiggle room in recruiting new players unless some existing ones leave.

Having a new signing does not mean that the whole fee is charged as an expense immediately due to the accounting dark art that is amortisation.

Amortisation is the effective rental cost of a player in relation to the transfer fee paid for his registration.

Numbers for individual transfer fees are difficult to obtain, but amortisation totals give a good long term indicator of the investment in players by the club.

Amortisation is the transfer spread over the contract life so when West Ham signed Haller for £40 million on a five-year contract, this will result in an annual amortisation charge of £8 million a year.

Squad amortisation for 2018/19 was a record £57 million, up 40% on the previous season, again suggesting investment was made, but the decisions made by the recruitment team were unsuccessful.

Overall West Ham’s amortisation cost for the last decade was £270 million, and has increased noticeably in recent years, but this has not turned into better football being seen by fans.

Under a succession of managers West Ham’s recruitment policy looks poor when compared to the amortisation costs of the likes of Spurs or Leicester, with Liverpool’s being only moderately higher too.

Looking at the rapid increase in amortisation costs indicates that West Ham have spent large sums recruiting players from other clubs and paying them handsomely, but the quality of the recruitment must be called into question.

Life in the boardroom at West Ham isn’t easy in the sense that many fans blame Gold, Sullivan and Brady for the lack of progress on the pitch, but this is offset by a 27% pay rise for West Ham’s CEO.

Ed Woodward at Manchester United, another unpopular executive, is the highest paid club CEO but there are now a considerable number earning million pound plus sums each year.

Some West Ham fans may be surprised that the club did make over £12 million profit last season from selling players, nearly all of this is likely to be in respect of Kouyate joining Crystal Palace and Reece Burke going to Hull.

Profits

So overall West Ham went from a profit before tax of £18 million to a loss of £28 million in 2019.

By looking at the above table it’s evident that West Ham’s player policy is the main reason for the reversal of profits is player related.

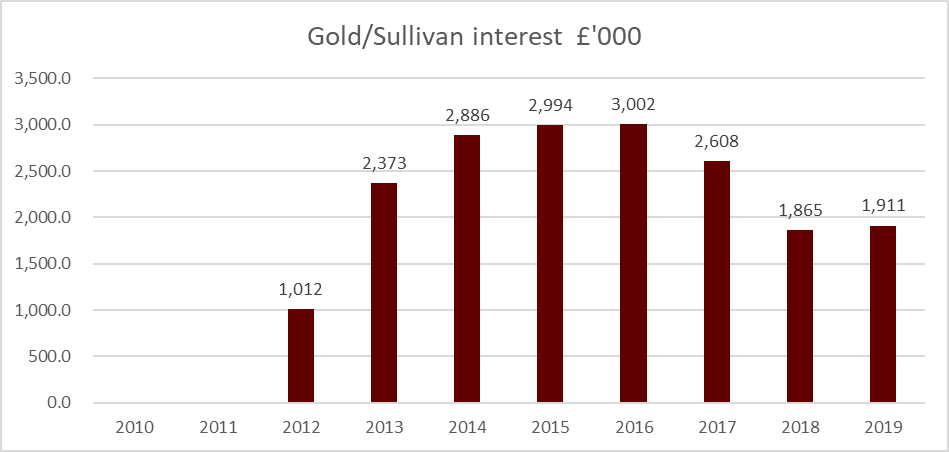

Owners David Gold and Sullivan have not endeared themselves to fans by charging a further £1.9 million on their £45 million loan to the club though, taking the total interest charges to over £18 million, not a game changer to the club, but high when compared to some other owners, including Mike Ashley at Newcastle, who for all his faults has lent £111 million interest free. .

West Ham managed to fund the loss last season by borrowing money secured on future broadcast rights, whilst this is a common event in the Premier League it will cause problems if the club is relegated.

Losing Premier League status would be challenging for West Ham, but the auditors seem happy with the club’s going concern status and many players have significant relegation wage clauses in their contracts.

Player trading

West Ham signed players for £108 million in the year to 31 May 2019 as Anderson, Diop, Yarmolenko, Fabianski and Co were recruited. Sales were a modest £14 million. Since then the club spent a net £36 million in the summer 2019 window and Bowen, Randolph and Soucek in January 2020.

Over the course of the last decade West Ham spent a total of £444 million on players and recouped about a third of it in sales. What is noticeable is that the club has made many of the player signings on credit, which could be a concern if the club is relegated.

Funding

West Ham have borrowed money from a variety of sources. Gold and Sullivan have lent £45 million and presently charge interest at 4.25%. In addition, there was a £42 million loan from Rights and Media Limited, which was half paid off shortly before the year end and so reduced the liability at the balance sheet date. The loan was then effectively renewed shortly after the year end. David Sullivan candidly admits that 75% of the club’s income is effectively generated between 31 May and 31 July.

The criticisms levelled at the owners are that other club owners have lent money to the club and not charged interest, including the US investors at West Ham, who own 10% of the company. Whilst the interest charged ultimately is relatively insignificant (1.8%) of revenue if the club is not delivering on the pitch then it sticks in the throat of those who have given up what has been a huge part of their lives for an anodyne extension to a shopping centre.

Summary

So, where does this leave West Ham? There is no doubt that the Gold, Sullivan and Brady are unpopular with a large proportion of fans. They hugely overpromised and underdelivered in relation to the benefits of the stadium move. The very big financial gap between West Ham and the ‘Big Six’ is as big as ever. What was so great and identifiable historically about West Ham has been lost in the shape of being representative of East End working class culture has been replaced with a very bland, very corporate and very anonymous ‘matchday experience’ that is for many a price too high. If the club was closer in the Premier League table as it is in the income and wage table then perhaps a lot would be forgiven, but until then it’s going to be a hostile environment and a sense of loss by the fans.