Norwich City: In the Country

Introduction

Norwich City Football Club Ltd announced its financial results for the year ended 30 June 2018 recently.

Norwich are the third team in last year’s Championship to produce their results, following Hull and Birmingham. It may be a new EFL rule that clubs whose name ends in ‘City’ are legally obliged to publish their accounts before any others, or it may be coincidence, though with Shaun Harvey in charge anything is possible. Any tables for the division as a whole use figures from 2016/17 for other clubs.

Norwich finished a forgettable 14th in 2017/18, which, given their financial performance, will have been seen as a bit bobbins by fans. Manager Daniel Farke doesn’t seem under too much pressure at present, despite a win ratio that is lower than predecessor Alex Neil.

Summary

Income down 18% to £61.7 million

Wages down 1% to £54.2 million

Recurring trading losses down 9% to £9.5 million

Player purchases down from £19.9 to £15.5 million

Player sales up from £18.4 to £54.8 million

Income

Every club must split its income into at least three categories to comply with EFL League recommendations, matchday, broadcasting and commercial. Norwich go a bit further but what is very evident is the part played by parachute payments in terms of its contribution to total income.

Norwich’s matchday income rose by 7% last season to £9.8 million last season. The club sells out most matches at Carrow Road, and season ticket sales only fell by 2% to 20,557. Average attendances have been a constant 26-27,000 over the last few years.

Norwich managed to extract more money from fans than the previous season, this is mainly due to better cup progress and ties against more glamourous opposition in the form of Chelsea and Arsenal than the previous season.

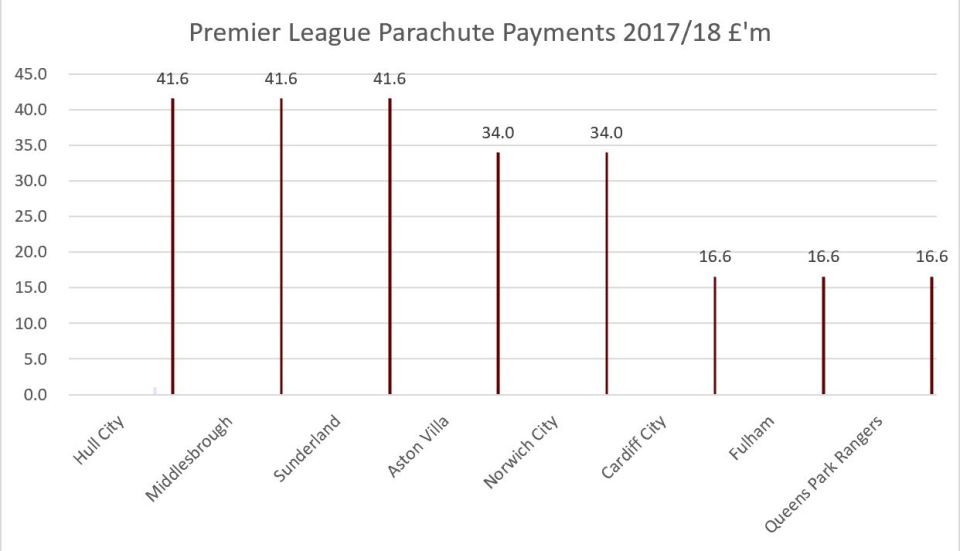

Broadcast income for clubs in the Championship varies significantly due to parachute payments. Clubs now receive these for three years (two if relegated in first season following promotion) and this is tapered as 55%, then 45% and finally 20% of the equally shared element of Premier League payments. However, if a club is promoted to the Premier League and then relegated immediately it loses the third parachute payment.

For clubs who are not in receipt of parachute payments, they receive about £6.5 million in the Championship for broadcasting. About £4.3 million of this comes from ‘solidarity payments’ from the Premier League as a share of the PL TV deal, and the remainder from the EFL’s own deal with Sky.

The EPL, being the sneaky scamps that they are, have changed the formula in relation to how it calculates payments to EFL clubs from 2019/20, which is likely to result in a further decrease.

New TV Distribution Rules: Everyone’s A Winner. – Price of Football

The reduction of about £30 million this season in broadcast income will make belt tightening and player sales paramount if the club is not promoted.

Parachute payments are a double-edged sword, clubs need to have them as an insurance policy when in the EPL as even with relegation wage clauses many would go into administration if they were unavailable.

The research suggests that they are worth about 6-8 points of an advantage on average to clubs who are receiving them. This has not stopped clubs in recent years being promoted whilst not in receipt of parachute payments though, as fans of Huddersfield, Brighton, Blackpool, Watford and Palace etc. will testify.

‘Other’ income fell by 15% to £13.1 million. The main contributors to this are catering (no idea who might be behind that) and deals with commercial partners.

The contribution made by this income source again helps make the club competitive in the division.

Overall Norwich are likely to have had one of the highest income levels in the Championship last season, but the lack of parachute payments in 2018/19 is likely to put then down to the level of the likes of Brighton and Derby in the graph below.

Norwich therefore had £62 million coming into the club last season, which may make some fans wonder what they did with it, leading to an analysis of…

Costs

Player costs

Norwich’s main costs, like those of nearly all clubs, were in relation to players, in two forms, wages and amortisation.

Norwich’s headline wage bill, at £54 million, initially suggests that the club has ignored the impending income crisis arising in 2018/19, but there is more to it than meets the eye.

Norwich’s wage bill meant that the club paid out £88 in wages for every £100 of income. Included in the wage cost is £12.2 million of ‘charges relating to contracts of certain players whose registration value is impaired and whose contracts have been classified as onerous’.

What this means in English is that the club signed a load of duffers who aren’t worth the money they were being paid. In order to get rid of the players (and Canaries ITK have suggested this could be the likes of Nasmith, Jarvis and Wildshutt) have paid up their contracts as otherwise no one would want to buy them.

The good news for Norwich fans is that the wage bill for 2018/19 will be considerably lower as a result, which will become increasingly important as FFP rules start to bite.

Wage control in the Championship is poor, with clubs on average paying out £100 in wages for every £100 of income. This means there is nothing left over to pay for transfers, rent, ground maintenance and other overheads, resulting in most cases in owners having to fund these costs or the club relying on player sales to break even.

Norwich’s wage bill last season was not in line with a club finishing 14th and even if the payments to the useless ones are excluded they are still close to the top of the table.

One group of people who didn’t do too well out of the season were the salaried directors. Norwich used to pay amazing sums to their execs, but this has come down sharply in recent years.

The previous season Jed Moxey had earned £417,000 for a half year of mediocrity (plus kerching-ing £772,000 as a payoff when asked to vacate his position), but this season the highest paid director ‘only’ earned £108,000.

Player Amortisation and impairment

Amortisation is the accounting nerdiness for how a club deals with player transfers in the profit and loss account. This is achieved by spreading the transfer fee over the life of the contract signed. For example, when Norwich signed Grant Hanley for £3 million on a 4-year contract, this works out as an annual amortisation cost of £750,000 for each year of the contract. The amortisation cost in the profit and loss account represents the total for all players signed for fees in previous seasons.

Norwich’s amortisation cost nearly tripled in 2017/18 fell slightly as some players were sold.

The increase in amortisation charge meant that Norwich’s charge in 2018 was higher than that of promoted Brighton and Huddersfield the previous season.

To add to Norwich’s player costs there was an impairment charge of £9.4 million. This arises when a player is signed for a fee and the club then conclude that he’s overvalued, so write down the transfer fee. The good news here for Norwich is that by accelerating the player write down it reduces amortisation costs in future years.

Adding amortisation, wages and impairment together gives a total player cost of nearly £64 million. This exceeds Norwich’s income for the year, although some of these costs are non-recurring in nature.

Profits and losses

Profit is income less costs, but it contains lots of layers and estimated figures. Norwich, like all clubs, show a variety of profit measures in their accounts so they need a bit of explanation.

Operating profit is income less all the running costs of the club except loan interest. It is a volatile figure as it includes one-off non-recurring costs such as profits on player sales and redundancy packages for managers that make calculating the underlying profit figure difficult.

Norwich had a headline operating profit of £19 million for the year to 30 June 2017/18.

The £19 million profit looks superb, only exceeded by Hull, also relegated an in receipt of parachute payments, especially in the context of a Championship which made total operating losses in 2016/17 of £260 million, but there’s more to this profit figure than meets the eye.

Stripping out player sale profits and other non-recurring items (redundancies, legal cases, debt write offs etc.) gives a more valid profit measure called EBIT (Earnings Before Interest and Tax).

Norwich has profits on player sales in 2017/18 of £48 million. Whilst fans will think of the sales of Jacob Murphy and cheeky scamp Alex Pritchard during the season, it looks as if Norwich have also included the sales of James Maddison to Leicester and Josh Murphy too. This is because both these deals went through before the club’s year end of 30 June 2018. There’s nothing wrong with such an approach, but if Norwich fans were banking on a big profit on player sales in 2018/19 they’re going to be disappointed.

Norwich’s operating profit of £19m therefore becomes an EBIT loss of £9.5 million, or about £190,000 a week, once the player sales, impairments and accelerated wage figures are stripped out.

Nearly every club in the Championship has significant EBIT losses, which were £392 million in 2017, as many owners gambled on spending big to try to secure promotion to ‘the promised land’ of the Premier League, which Norwich fans will probably admit is in reality celebrating getting a corner in a routine pasting at the Etihad and getting out the cigars when defeating Burnley and Bournemouth.

If non-cash costs such as amortisation and depreciation (depreciation is the same as amortisation except this is how a club charges a cost for other long-term assets such as buildings) are excluded then another profit figure called EBITDA (Earnings Before Income Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation) is created.

This is liked by professional analysts as it is the nearest thing to a cash profit figure, and it is more likely to be a positive figure than the likes of EBIT.

Adding back these costs, Norwich moves back into profit

In addition, if a club has loans then the loan interest is then deducted to arrive at profit before tax. Norwich’s interest cost in 2018 was about £10,000 a week.

FFP losses

A few clubs (Birmingham, Villa, Sheffield Wednesday, Derby) have been subject to gossip and rumour in relation to breaches of FFP rules in the Championship in recent months, but Norwich have not been amongst them.

Under EFL FFP rules, a club is allowed a maximum loss over 3 seasons of £39 million. However, FFP starts with profit before tax but the losses exclude the following

- Infrastructure costs such as depreciation

- Academy costs

- Women’s football costs

- Community scheme costs

Norwich have a category 1 academy, which is estimated to cost about £4.5 million a year, so looking at the three years to June 2018 gives a rough FFP profit of £49 million

This is excellent news for Norwich as it means that whilst they will suffer significant income deductions in future years if still in the Championship they should be within FFP limits for a few years.

With clubs such as Norwich abiding by the rules, it’s clear that the EFL will be under pressure to punish those that have taken a cavalier approach to FFP, so there could be points deductions in the Championship soon if rumours are true.

Player Trading

Norwich spent £15.5 million on new players in the year to 30 June 2018, which is reasonably high by Championship standards. The club also had player sales of £54.8 million, although these do include Maddison and Josh Murphy in June 2018.

The large spend on players is why the amortisation charge in the profit and loss account is so high. Fans often point out that clubs also sell players and that net spend is a better measure of a club’s investment in talent.

Norwich have historically aimed to broadly break even in terms of their player trading budget, but it looks as if the sales in 2017/18 were done with the aim of ensuring the club has sufficient cash to survive without parachute payments.

Most big transfers are paid in instalments these days, and Norwich were owed £42 million from other clubs for outstanding payments at 30 June 2018, but only owed £14 million themselves. The receipt of these instalments should ensure the club can survive financially in the short to medium term without any major crises.

Hidden at the back of the accounts is a wee note showing that since 30 June 2018 Norwich has signed players on loan deals, with a total loan fee of £4.2 million, plus a further £9 million, presumably if the club is promoted.

Investment

Club owners can invest three ways, sponsorship, lending or buying shares.

During 2017/18 Norwich went to fans and borrowed £4.8 million to develop the academy, plus the directors threw in £250k themselves. It meant that at the end of the year Norwich had over £16 million in the bank, enough to tide the club over for 2018/19.

Summary

Norwich’s finances for 2017/18 are a bit weird, the club seemed very keen to accelerate both good news (player sales) and bad (player write-downs and contract write offs). Clearly Ed Balls and co are keen to communicate the message that there’s no money spare. This seems a prudent approach, but as we’ve seen in the wider economy, austerity, once started, never seems to end.

Data Summary