Hull City 2018/19: Doppelganger

Assem Allam, the Hull City owner, is not a popular man with the fans of the East Riding Championship club.

Last season the club finished 13th in the Championship which was a reasonable if forgettable position.

Losing 8 games out of the first 12 had left Hull at the bottom of the division in October but things improved on the pitch slowly and at one point Hull were in with a chance of making the playoffs.

A look at the club’s accounts reveals a mixed bag too, although the club deserve some credit for (again) being the first of the 92 to publish results for the previous season.

Many fans believe the Allam’s have put their own interests ahead of the club and stunts such as changing the name of the club’s company to Hull City Tigers Limited have not helped the situation.

Income

We need to split a club’s income into three main areas, matchday, broadcasting and commercial, to get a feel for how a club is performing both historically and compared to others in the division.

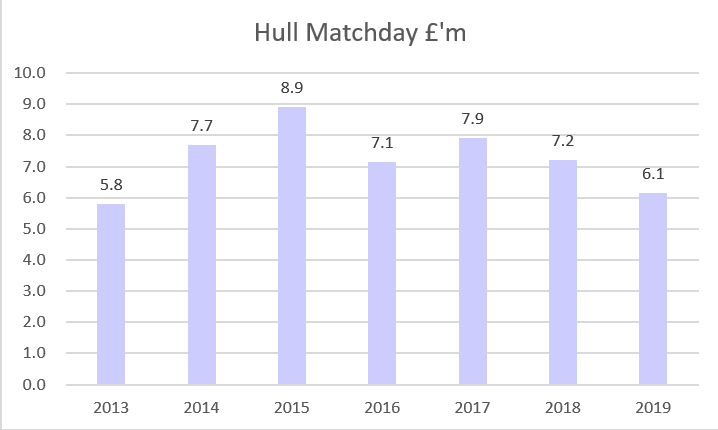

Earnings from matchday sales last season fell by nearly 15% to £6.1 million, the lowest for six years.

Average attendances fell below 10,000 as fans voted with their feet in terms of the toxic relationship with the owners, as well as a poor start to the season on the pitch.

Relative to other clubs in the division (from 2017/18 figures) Hull’s matchday income is reasonable but doesn’t give the club much of a base to compete for players.

Selling deals to sponsors and commercial partners is challenging for a club such as Hull due to geographical and historical reasons and being in a city that also has two rugby league teams, which helps explain why such income source has decreased by 85% since the club was in the Premier League in 2016/17.

Leeds and other large clubs in the Championship can sell the size of their fanbases to sponsors, but the likes of Hull have to fight over the scraps, resulting in the likes of my all time favourite shirt sponsor Flamingoland being plastered over the shirt a few seasons ago.

In being a member of the Premier League in 2016/17 Hull have had the benefit of two years of parachute payments to help deal with the legacy of large player contracts and outstanding transfer fees from the top tier.

Next/this season (2019/20) Hull will lose parachute payments which are usually given for three seasons but this is reduced to two if a club is promoted and then relegated in the first season in the top flight, as happened in 2016/17.

Going into the EFL broadcasting deal in 2019/20 will mean that Hull’s broadcast income will fall to about £7 million from £40 million, which will result in a major belt tightening exercise.

Every club in the Championship gets about £2.3 million from the EFL’s own deal with Sky as well as a £4.3 million ‘Solidarity’ fee from the Premier League, and a separate fee for each match that is chosen for live broadcast.

Relative to most clubs in the Championship Hull fared very well in terms of broadcast revenue last season but they will drop to close to the bottom of the table in 2019/20.

In the EFL some club owners feel the deal negotiated by the unpopular Shaun Harvey short-changed them but realistically they will struggle to generate significantly more than the existing arrangement, which is split 80% to the Championship, 12% to League One and 8% to League Two clubs.

Even if the Sky deal, which lasts five years, was scrapped, it’s unlikely that a new broadcaster would be willing to pay much more, as armchair fans tend to focus on the elite Premier League teams and the remainder of that division are simply fortunate that collective sale of rights takes place.

Overall Hull’s income dropped to £48 million in 2018/19 but unless the club is promoted expect it to drop to levels similar to those earlier in the decade of about £17-18 million.

No business should be over-reliant on a single income source but Hull had 83% of their coming from broadcasting last season and will suffer a significant hit when this declines.

Total income for Hull last season exceeded that of the likes of Leeds and Derby (or Frank Lampard’s Derby County, to give them their proper name from last season) which will suspect fans of all three clubs we suspect.

Costs

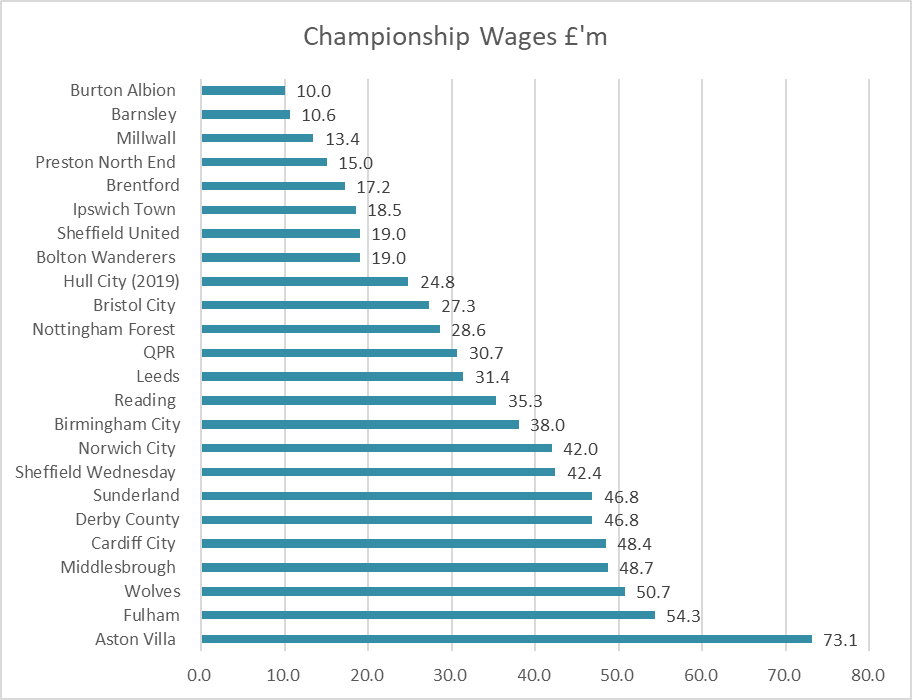

Having to compete in the Championship is expensive and the main reason for this is due to player costs in both wages and transfer fees.

Unlike in League One and League Two, the EFL do not operate a soft wage cap in the Championship and this means that some clubs live beyond their means in terms of what they pay players.

Rollercoaster wage totals are a feature of Hull’s wage bill over the last decade as the impact of promotion, relegation and bonuses is highlighted in the figures above.

Spending less on wages than for the last six years meant that Hull’s squad contained a mixture of players who were reluctant to take a pay cut to leave alongside untried signings and academy step ups.

Despite the 20% decrease in wages we estimate players at Hull were still on about £600,000 for last season, so sympathy is unlikely to be in great supply for them, although expect this figure to fall significantly in 2019/20.

A lot of clubs in the Championship pay more out in wages than they generate in income but Hull are at the bottom of this table but this may change as parachute payments cease.

Year on year over the last decade Hull have had very good wage control by Championship standards, but they have also had the benefit of promotions and the accompanying parachute payments during the period.

No other industry than football would tolerate spending more on wages than income but from a fans’ perspective so long as the club is promoted the end is justified by the means.

Intangible asset (transfer fee) amortisation is the other main expense in relation to players where the transfer fee is spread over the life of the contract.

George Long signed for Hull for about £135,000 on a three year contract, so his annual amortisation cost would be £45,000 (£135,000/3).

Hull’s total amortisation cost for the squad last season was £13 million in relation to a squad which at the start of the season cost £36 million.

The amortisation fee in the profit and loss account considers all the squad players signed for fees and reflects the longer-term investment in transfers.

Some Hull fans might be surprised the amortisation charge increased last season but this reflected that relatively few high cost players were sold.

One additional operating cost that Hull have to pay is rent in relation to the stadium. Under the agreement with the Allam owned Superstadium Management Company Limited Hull appear to have to pay rent that increases by 10% a year. This has resulted in rent increasing nearly doubling from £425,000 to £835,000 since 2014.

Profits/(Losses)

Profits are revenues less costs and Hull just about broke even last season and have made profits in three years out of the last nine, again on the back of Premier League membership.

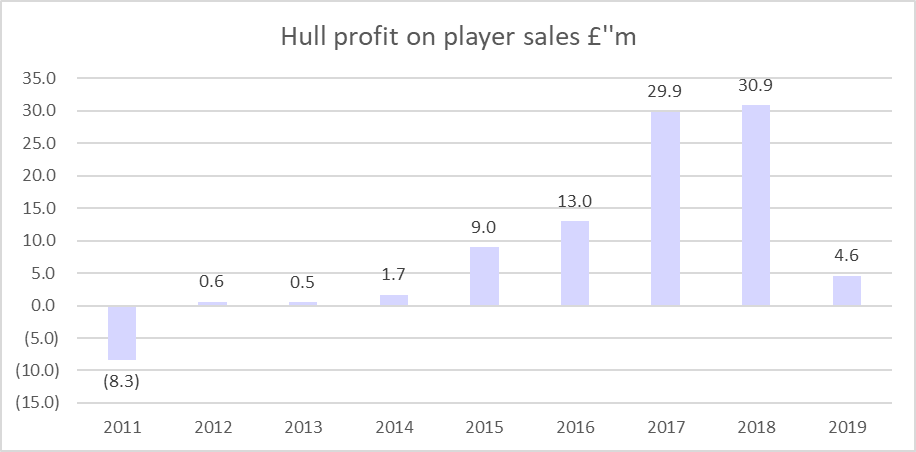

The only way that clubs can usually reduce these losses is via player sales or owners underwriting them. Hull have had relatively some success in terms of player sales in recent years making profits on player sales of £82 million.

The Allam’s have lent money to Hull but have charged interest on the outstanding loans. Hull have paid out nearly £23 million in loan interest so far this decade although not all of it necessarily relates to the owners.

Player Trading

Last season Hull were relatively quiet in the transfer market by historic standards.

Net transfer income of £2.7 million in 2018/19 was not competitive by Championship standards.

Owner Funding

Club owners can invest money in three ways, loans (which may or may not be interest bearing, share issues or related party transactions such as the stadium sales at Derby, Villa, Sheffield Wednesday and Reading.

Hull repaid the Allam’s about £13 million last season to take the sum down to £50 million, which may or may not be a coincidence of the alleged price the Allams are looking for when selling the club.

Conclusion

Hull financially have done well to break even on a day to day basis last season but that ignores that their main income source is about to dry up.

Unless a speedy resolution to the conflict between the owners and fans takes place the club is going to struggle to compete in the Championship and attendances could fall even further below the present levels.

Some might say the accounts are out extremely early to give the Allams more time to market the club to potential investors before there’s a deterioration in the financial numbers in 2019/20.