Crystal Palace 2017: Dancing In The Dark

Starting with the elephant in the room, we’re Brighton fans here on this blog, so stop reading if you’re a Palace fan and think the aim is to have a pop at your club’s finances.

The Palace accounts cover the year to 30 June 2017, they were due to submitted to Companies House by 31 March 2018 but were a few months late.

Eagles fans (and those of their rivals) have speculated as to why the club has taken such an approach, as all other clubs had submitted their accounts some time ago.

Vast amounts of social media space have been taken up with fans arguing, often with themselves, as to the reasons behind the delay, but our focus is on what has been published, so we’ll leave point scoring and petty one-upmanship to others.

Income

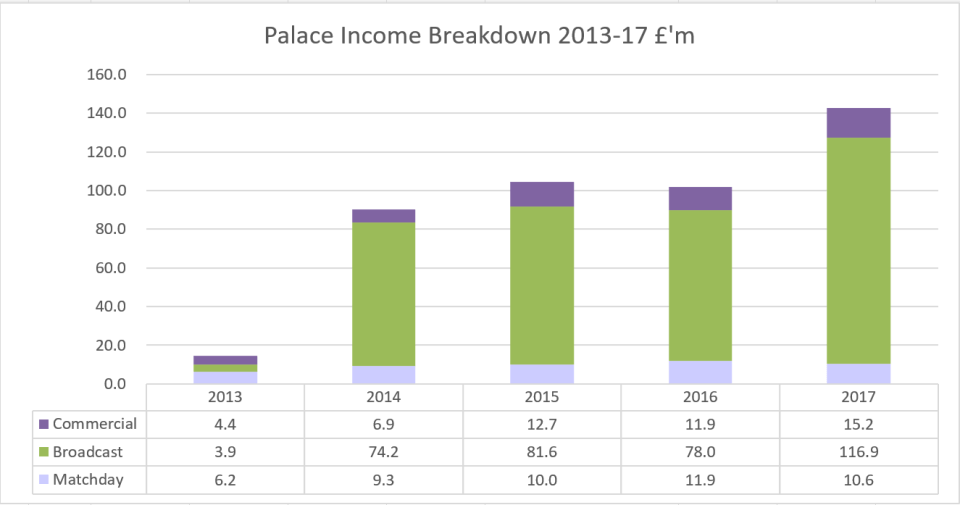

Every club must split its income into at least three categories to comply with Premier League recommendations, matchday, broadcasting and commercial.

Palace’s matchday income fell 11% in 2017 to £10.6 million. This initially appears odd as attendances rose from 24,635 to 25,160.

A quick look at Palace’s matches the previous season suggests that their success in getting to Wembley twice in the FA Cup would have been significantly beneficial to the club’s matchday coffers. Combine this with the cap on away fan ticket prices in 2016/17 at £30 (Palace were charging £32-£40 the previous season) and the fall in revenue becomes more understandable.

Residing probably where their fans would expect to see them in the matchday income table, Palace have more matchday income than many provincial teams due to being able to charge London prices, but less than those with bigger stadia and regular European home games.

In terms of broadcasting income, Palace were major beneficiaries of the new BT Sport/Sky TV deal, with an increase of 50% due to the £8bn three-year deal kicking in for 2016/17. This was combined with the club appearing on TV four times more than the previous season (worth about £1m per appearance) and £2m for prize money in finishing a place higher in the league table too.

Selhurst is a good ground from which to broadcast from due to the noise generated, and whilst it winds up some opposing fans (and some of Palace’s too) it looks good on the box, more than the sterile atmosphere at some big grounds full of corporate backslappers.

How much further Palace can go up the table is open to question as they only had 12 matches live in 2017/18 but this was offset by an 11th place finish worth an extra £6m compared to 2016/17.

How the Premier League divides money up is complex (and about to become more complex after the League chairmen stitched up clubs in the lower league with a new formula which reduces money available to greedy grasping clubs such as Bury, Grimsby and Accrington Stanley). Simply put half of the money is split evenly, a quarter linked to live domestic TV appearances and the rest is based on the final league position, with each place worth an extra £1.9m).

A lot of clubs in the Premier League are very dependent upon broadcast income and Palace are no exception, with nearly £5 in every £6 coming from this source. There are mutterings from fans of many clubs that TV money ruins the game in the top flight, but we would argue that it is a democratising force, allowing the likes of Palace to compete for decent players and pay them accordingly. This makes the Premier League more competitive, something the owners of the big clubs are out to destroy, especially since Leicester broke their little cartel by winning the Premier League.

Successfully being able to outbid most clubs in Europe apart from the Champions League regulars for players has allowed clubs of the stature of Palace to recruit the likes of Cabaye and keep Wilfred Zaha. Even expensive flops such as Benteke aren’t going to drag the club down whilst they remain in the top division.

Commercial income is again where you would expect it to be. Less than the global brands masquerading as local representatives and ahead of clubs that are so spectacularly inoffensively dull that no one wants their products to be associated with them (and yes, we are looking at you Watford there). A rise in commercial income of 28% is impressive although both the shirt sponsor and manufacturer were the same as the previous season the club may have signed deals on the back of the previous season’s FA Cup run (or earned bonuses that kicked in on the back of this).

Ridiculous gaps between the likes of United and most other clubs can only be overcome on the pitch if there are other sources of income, which brings us back to the view that the present split of broadcast income helps level the playing field…and if this is only by a small amount it surely must be welcomed.

An additional source of income for Palace in 2016/17 was £4 million of ‘other income’. In the accounts this is described as ‘compensation for…award in favour of the club by the Premier League Manager’s Arbitration Tribunal. This would appear to the money Palace received when former manager Tony Pulis tried to stiff the club by taking a £2.5m bonus for keeping them up in 2013/14 and then left.

Pulis was however only entitled to the bonus if still at the club at 31 August but quit having asked for it to be paid early and then resigning on 14th August. Palace sued for the bonus to be repaid by Pulis and the case went to tribunal.

Pulis’s reputation as an obnoxious deceptive shitbag that was established by the tribunal sadly has not prevented him from finding other work since then as a manager.

Costs

Wages

Palace’s main costs were in relation to players, and the wage bill rose by 39% to nearly £112 million, nearly six times the amount they paid out when promoted from the Championship in 2013.

Having a wage bill rising at this rate does look alarming, increasing as rapidly as the notches on Katie Price’s bedpost. Normally wages rise substantially when a club is either promoted or there is a new Premier League TV deal commencing. This would explain the jumps in 2014 and 2017, but in between too there have been significant increases in wage costs as the club has invested in new players and keeping some existing ones.

A wage bill of this magnitude puts Palace almost neck and neck with Leicester, who had won the Premier League the previous season and had the benefit of Champions League participation in 2016/17 too. The extra wage cost is on the back of substantial player recruitment for the season, as players on big transfers expect to be rewarded in line with the fee paid.

It’s difficult to see the rationale behind Palace’s wage rise compared to that of many other clubs. The three promoted clubs are self-explanatory, City had to fund Guardiola’s spending spree, Leicester had new contracts having won the Premier League (and had Champions’ League bonuses to pay). Chelsea’s wage bill fell despite winning the Premier League because of lack of Champions’ League participation. Premier League wages overall rose by ‘only’ £135 million (6%) as the clubs promoted had lower totals than those they replaced (Villa, Newcastle and Norwich).

Representing £78.30 of cost for every £100 of income in 2016/17, wages at Palace are proportionately the highest of any Premier League club. This suggests both Pardew & Allardyce we’re backed during the season. It does however limit wriggle room to increase wages in future years unless they generate extra income, hence the proposal to expand Selhurst.

Because of the boost in staff costs, Palace players have an average weekly wage of over £50,000 a week.

Rich owners of Premier League clubs have managed to restrain wage rises through the introduction of Short Term Cost Control (STCC) rules for 2016/17. STCC is designed to prevent what Alan Sugar described as the ‘Prune Juice’ effect, where additional broadcast income flows straight through the club into wages as unscrupulous working class players demand more money from the poor multi-millionaires, private equity funds and sovereign wealth bodies which represent Premier League clubs’ owners in the present age.

STCC works by limiting player (not that of all employees) wage rises to £7million a season plus any non-broadcast income plus the average profit on player sales over the last three years.

Looking at Palace, they had a wage increase of £31.2 million, which in order to satisfy STCC would look something like this.

It’s not sure if the Pulis money is allowable, but we have bunged it in just in case. As far as Palace are concerned, it effectively means that provided non-player wages increased by less than £3.2 million then they are within the limits.

Employing the likes of Sam Allardyce won’t have been cheap and it is unclear how much it cost the club to sack Alan Pardew, but this is likely to be in the overall wage cost.

One of the directors also had a substantial pay rise.

Only one director appears to be on the payroll, and the likely recipient is Steve Parish. There’s nothing wrong with Parish earning such a sum, he’s been a contributor to the club being promoted and securing a position in the Premier League. The sum earned is broadly in line with the average income for a first team player.

The accounts do appear very defensive in relation to this money though. First there is a note in the directors’ report stating that a bonus the previous season had been foregone and then implied that the bonus and more had been invested in the club.

Directors are entitled to be paid, and with the riches of the Premier League the Palace recipient is not the highest paid in the division (step forward Daniel ‘Steve Austin’ Levy at Spurs) nor the lowest (although Manchester City’s figures are best filed under creative accounting as whilst the club’s accounts show a zero figure, the parent company, which also owns clubs in Australia, the US and South America has total key management pay of over £4 million).

The note also showed the directors’ commitment in terms of the amount of money injected into Palace to fund the player purchases under Allardyce in January 2017.

Then in the footnotes to the accounts further explanation appears showing both the gross and net sum received by this director. The inference being that by earning ‘only’ just over £1.1 million net Parish (assuming it is him) is somehow slumming it.

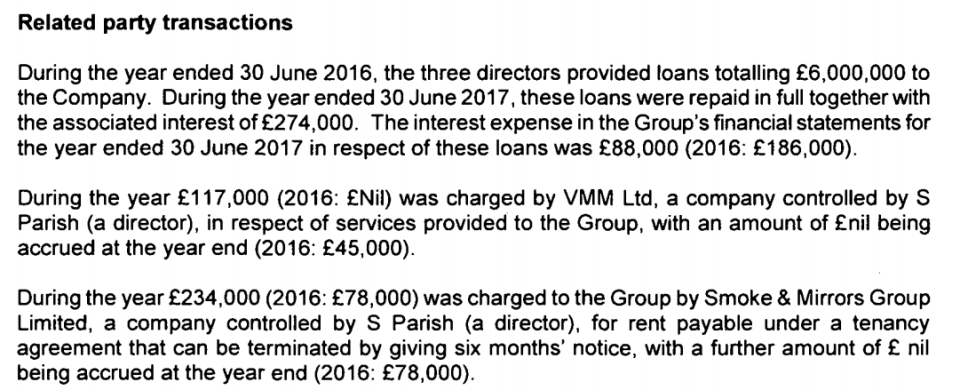

In addition to the salary earned, Steve Parish controlled companies that sold services to Palace.

VMM Ltd appears to be a property company with one employee, and Smoke & Mirrors Group Ltd by all accounts rents a property in Soho to Palace, which seems a bit odd, as does tripling the rent for 2016/17.

Some things from the directors’ comments seem inconsistent though. As the cash flow statement for 2016/17 shows that the shares issued by the club have been used to pay back loans to former shareholders and loans from directors have been repaid along with interest. The loan from the parent company in the year needs to be reviewed when the parent publishes its accounts.

The mysterious third party proposed investment mentioned in the directors’ report does not seem to be mentioned in the cash flow statement. This could be because it was received in 2017/18, although you expect to see this mentioned in the note to the accounts that summarises post year end transactions.

Player Amortisation

This is how a club deals with player transfers in the profit and loss account by spreading the cost over the contract period. So, when Palace signed Benteke from Liverpool in the summer of 2016 for £27 million on a four-year contract, this results in £6.75 million (£27m/4) being added to costs for four years.

The total amortisation cost for the club for 2016/17 rose 80% to nearly £33 million, reflecting the investment in the playing squad in both transfer windows.

Palace’s figure is a record for them but about mid-table by Premier League standards.

If wage and amortisation costs are combined, then Palace are the only club in the Premier League to have spent more money on total player costs than they generated in income.

Profit

Profit is income less costs, but it contains lots of layers and estimated figures. Palace’s profit and loss account refers to a few different profits, so they need a bit of explanation.

Operating profit is income less all the running costs of the club except loan interest & tax. On the face of things, it looks as if Palace have had a good year in 2016/17, with an improvement of nearly £19 million.

Included in operating profits are some volatile income and costs such as profit on player sold and the income from successfully winning the claim from obnoxious bellend crook Tony Pulis and player write-downs. Palace made profits on player sales of £35m.

If these non-recurring items are removed, we get something called EBIT (earnings before interest and tax) which in theory is a sustainable/recurring profit figure.

Palace’s EBIT profits are less impressive, as the profit becomes a loss reflecting the increase in wages and other operating costs in the year.

The Premier League made EBIT profits of £147 million in 2016/17, but these vary substantially from club to club. Palace had the third highest EBIT loss.

If non-cash costs such as amortisation and depreciation (the same as amortisation except this is how a club expenses other long-term asset such as office equipment and properties over time) then another profit figure called EBITDA (Earnings Before Income Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation) is created. This is liked by professional analysts as it is the nearest thing to a cash profit figure.

The good news for Palace is that they made an EBITDA profit, the bad news is that it was the second lowest in the division. The Premier League made EBITDA profits of £1,183 million, of which £10 million was earned by Palace.

Player Trading

Palace splashed the cash in 2016/17 with over £104 million on player purchases such as Benteke, Townsend, Milivojević & Van Aanholt, making them the fourth highest gross spenders in the division.

The large spend on players is why the amortisation charge in the profit and loss account is so high. Fans will rightly point out that clubs also sell players and that net spend is a better measure of a club’s investment in talent.

Taking this into account Palace spent over £65 million net in 2016/17 and shows the extent of the achievement in 2013 in being promoted with a negative net spend (Sir Glenn Murray being recruited on a Bosman).

Palace once again come fourth in the Premier League in terms of net spend.

One concern for Palace is that many of the players who were signed have the transfer fees payable in instalments. Consequently, the club owed over £45 million in respect of fees at 30 June 2017, but also themselves were owed £11 million from player sales, to give a net player trading creditor of £34 million.

Palace’s total creditors come to £107 million. This is sustainable whilst they are part of the Premier League, and even if relegation does arise then parachute payments and potential player sales should enable debts to be paid.

In 2017/18 the club spend a further £42 million on players but this time there was far less recovered from sales.

Summary

Palace’s finances are a curate’s egg. Higher income and profits are offset to a degree by an investment in players which had significantly increased wages and player costs.

Fans might question the sustainability of a business model in which more money is expensed in player costs than in generated in income, which is a common occurrence in the Championship, but not the case in the Premier League.

Ultimately Premier League membership is the most critical element of income generation and here the club has been successful, so the directors would argue that the policy has worked.

The very defensive comments in relation to director wages and interest on loans paradoxically brings them into greater scrutiny, but at least the Palace owners aren’t stiffing the club for £14 million in interest, unlike Gold and Sullivan at West Ham.

Some questions remain, such as the source(s) of funding for the stadium expansion, but these are capable of being overcome, provided there are not significant interest costs on any loans.

As for the delay in sending in the accounts, there seems to be little justification.