Crystal Palace 2017/18: I Just Can’t Be Happy Today

Surviving in the Premier League is even tougher than getting there and an eleventh place position is testament to Roy Hodgson in guiding the club to another season at the top table.

Usually Palace start the season poorly and improve in the second half of the season and 2017/18 was no exception after the De Boer experiment was quickly jettisoned.

Sustainability from a financial perspective wasn’t achieved however as the club, despite record revenues, lost £750,000 a week from day to day operations and was reliant upon the club owners to finance the gap.

An increased capacity Selhurst Park is part of the club’s strategy to improve the finances in the long term and this should improve the financial performance in the Premier League.

Income

Nowadays all clubs split income into at least three categories to comply with EPL recommendations, matchday, broadcasting and commercial.

Nearly all ‘Other 14’ clubs are very dependent upon broadcast income for the lion’s share of their earnings and Palace are no exception.

A new TV deal in 2016/17 was the driver of the big increase that season, but Palace’s 11th place finish earned them an extra £6 million in prize money in 2017/18 to £121 million, slightly offset by being chosen for live broadcasts two fewer times than the previous season.

Having a reliance on broadcast income is fine so long as the rules don’t change, and it’s sad to see the greed of the ‘Big Six’ force through a new method for distributing money from TV so that the rich get richer from Premier League International Rights.

Relating broadcast income to live appearances and final league position has a lot of merit but the existing formula has worked successfully for years and allowed clubs such as Palace to retain their best players, making the Premier League more competitive and unpredictable.

Europa and Champions League participation by the regulars ensures they have more broadcast income from UEFA than the remainder of the Premier League, so it is nothing but naked greed from foreign owners that has driven the new distribution model from 2019/20.

Income from matchday for Palace has been relatively static due to ground capacity constraints and the club has been reliant on cup runs to boost totals as price freezes and sold out matches mean this figure can’t be increased in the short term.

Diving into the footnotes of the accounts there was an ominous comment from chairman Steve Parish “with strong demand and a low relative cost to other Premier League London football ticket pricing will be further reviewed for the 2019/20 season” and Palace season ticket holders already know the consequences of this.

Palace’s matchday income is okay by Premier League levels but the board see scope for growth, especially in terms of hospitality consumers who are put off by the prices elsewhere in London and a revamped Selhurst could give the club an extra £5-10 million per season.

Eagles’ fans may not like the garish logo on the club shirts of new sponsor ManBetX but this has been a major contributor to the 20% increase in commercial income.

Getting new sponsors and commercial partners for a club isn’t easy unless you are one of the global brands with tourist fans, so Palace have done well here to keep growing this income stream.

Selling the club to sponsors is made slightly easier by being in London and the continued existence in the Premier League has increased the appeal of the club too.

Some clubs such as Manchester City, Everton and Stoke have the benefit of connected parties being willing to pay generously for commercial deals but Palace have had to do it the hard way.

Total income increased by 5% to £150 million which is more than ten times the money generated when Palace were in the Championship and total Premier League income since then is £590 million.

Even monied clubs such as Stoke, Swansea, Hull and Sunderland have been relegated in the last two seasons and struggled to make much of an impact in the Championship, which highlights just how important it is for Palace to avoid getting into a relegation fight as there are no guarantees of coming straight back up.

Very few clubs bounce back straight away in the Championship as has been seen in the present season where the three teams challenging for promotion in Sheffield United, Leeds and Norwich finishing last season 10th, 13th and 14th respectively.

Costs

Every fan knows that the main costs for a PL football club are focussed on player related expenses relating to player wages and transfers.

Player costs have accelerated in 2017/18 for nearly all clubs despite broadcasting income being flat overall as Sky/BT are in the second year of a fixed three year contact.

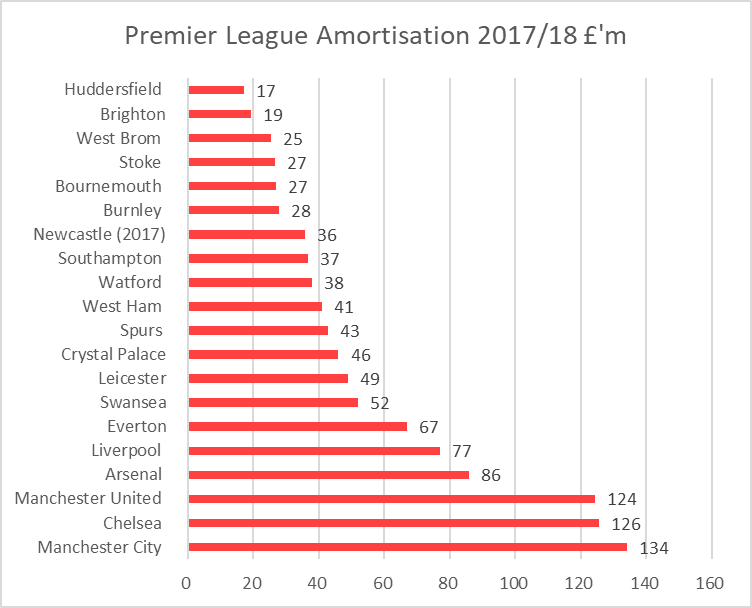

Amortisation is the cost of all the transfer fees paid by the club spread over the contract life, so when Palace signed Mamadou Sakho for £26 million from Liverpool on a five-year deal this works out as an amortisation charge of £5.2 million a year (£26m/5).

Rapid increases in amortisation are common in the Premier League if a club is promoted and stays in the division due to legacy players from the Championship being replaced by more expensive signings in the top flight over a number of years.

In signing Sakho, Riedewald, Sorloth and Jach Palace instantly increased the overall squad cost to nearly £200 million and the amortisation expense rose in line with this especially as the previous season saw Schlupp, van Aanholt and Milivojevic all arrive in January 2017 with only had a half year of amortisation on their transfers.

Spending more on transfer fee amortisation than London rivals Spurs and West Ham might surprise some Palace fans, but the club has been very active in the transfer market especially given the rapid turnover of managers at the club who want different players and styles.

Having spent money on transfers it’s no surprise that Palace’s wage bill grew last season, albeit by a relatively modest 5% to £117 million but that still put the club 9th in the wage table.

With such high wages and amortisation charges it is of little surprise that these costs absorb all of Palace’s income, representing £109 of costs for every £100 of revenue, meaning that the excess and all other overheads have to be paid for by either player sales or the owners underwriting the costs.

If Palace maintain their Premier League status for a few more seasons this is fine provided the owners continue to bankroll the club, but if not the club is at risk of major cutbacks as has been seen at Swansea in recent months.

The average wage at Palace is £56,000 a week but by all accounts some players are on about twice that sum which is usually accepted if the player is delivering (such as Zaha) but causes resentment when he is not (such as Benteke).

Having a wages to income spend at a constant in theory is a sign of good cost control but Palace do have a problem here in that UEFA recommend clubs should aim to spend no more than £70 in wages for every £100 of income and Palace have been above that benchmark in the last three seasons.

Profit

Agreeing what is meant by profit is always tricky as there are many variants, but the simplest definition is that it represents income less costs although deciding what is included in income and costs can muddy the waters.

Subtracting total costs from income gives what is called net profit and here Palace have a negative figure in the form of a net loss of £35.9 million.

This was perhaps bigger than expected although the rescue plan in recruiting a new manager and players after the De Boer experiment failed was expensive to repair.

Reports in the media recently have focussed on net profits especially with Spurs and Liverpool announcing ‘world record’ sums but the Premier League as a whole made a £286 million net profit in 2017/18 with those two clubs being responsible for three-quarters of the total.

A lot of the net profit can come from one off transactions, such as high tax charges (Manchester United’s was £63 million) or profits on player sales (Liverpool’s was £124 million, mainly through Coutinho going to Barcelona).

Profit from operations is perhaps a better measure as it ignores the distortions caused by tax and finance costs (some clubs pay interest on loans, others have interest free deals with owners) and concentrates on the money made just from regular business activities.

Operating profits for Palace are however little different to net profit as the club had a tax rebate that effectively offset the £35,000 a week in interest that was charged.

Nerds may be familiar with a profit measure called EBIT (Earnings before interest and tax) which strips out one off transactions, such as player sales gains and other irregular expenses and income.

Crystal Palace benefitted from these substantially in 2016/17 due to the sale of Bolasie to Everton which helped generate a £35m profit on player sales plus £4 million from the repulsive Tony Pulis in a court case where the club successfully recovered a bonus that he had claimed but to which he was not entitled.

A lot of clubs in the Premier League are dependent upon player sales to make ends meet, despite the benefits of broadcast income, as can be seen by EBIT losses being £184 million overall compared to net profits being a positive of £286 million.

Liverpool, for example, saw their profits fall from the world record £131 million quoted in the press to just £7m once the Coutinho profit (which won’t arise every year) was removed but Palace’s numbers barely changed as player profit sales were just £2 million.

Leaving out the amortisation cost (which is an accounting expense rather than a cash one) and depreciation (the same) gives something called EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation) and the good news for Palace is that this is a positive figure.

Earnings analysts like EBITDA because it is the nearest thing to a cash profit figure that can be easily calculated as it removes all the accounting nonsense which can be manipulated by unscrupulous businesses (Palace have NOT done this though as far as we can tell).

Player Trading

Delving into the footnotes of the accounts shows that Palace £54 million on new players in the year to 30 June 2018 but sales were much lower at just under £4 million.

Large investments in players, as has been already seen, led to the rise in the amortisation charge in the profit and loss account.

In each year in the Premier League Palace have spent more on player than they’ve generated in sales, which shows the board has backed the managers even if some fans think they should have spent more.

The total net spend by Palace since promotion in 2013 has been £184 million.

The Premier League pays inflated prices for many players, but the total net spend last season was over £1,240 million, with the usual suspects at the top of the spending table.

Liabilities for player signings can arise if clubs make signings on credit and agree to pay over a number of years via instalments and here there is cause for concern as Palace owed £49 million to other clubs at 30 June 2018.

Funding

Every club can obtain funding in three ways, bank lending, owner loans (which may be interest free) or issuing shares to investors and Palace have borrowed in recent years as new owners have put money into the club to underwrite its losses.

Palace benefitted from £38 million of interest free loans in 2017/18 and the owners have stuck in a further £24 million since June 2018 and this is before the stadium expansion project is implemented which will involve cash going out before it generates revenues.

It’s likely that similar investment will have to be made unless Palace cash in on the crown jewels in their squad this summer as underperforming players on big contracts may be reluctant to take the pay cut their talents perhaps deserve.

Summary

Every year Palace defy a poor season start and end up mid table and 2018/19 looks likely to repeat the formula, which is crucial as the club is vulnerable should relegation occur due to its disproportionately high player costs.

Relying on two or three star players to earn enough points to keep Premier League membership and paying them handsomely has worked to date and it would be foolhardy to change what has worked to date.

Sorting out the infrastructure cannot come fast enough if Steve Parish’s aim of establishing Palace as a top ten team in the Premier League as the relative lack of matchday revenue will hold the club back in what is becoming an increasingly important income source with broadcast deals unlikely to repeat their quantum leaps of the recent past.

Key Financial Highlights for year ended 30 June 2018

Turnover £150 million (up 5%)

Wages £117 million (up 5%)

Pre-player sale losses £38.9 million (up 50%)

Player sale profits £2.4 million (down from £34.7 million)

Player signings £54 million (down from £104 million)

3 Comments

Alan John Scofield

Excellent analysis and as someone has already posted on the Palace fans’ Holmesdale site, thanks for explaining amortisation! Whilst the accounts themselves are not good news you can’t have everything – where would you put it?

The Baron

The figures aren’t great but the owners do seem committed to the club and are prepared to back the manager and the stadium expansion plans financially.

Ryan

Susannah Reid does steve Parish with a strap on called Piers does she? rather cheeky.