Chelsea: Suffer Little Childreni

Introduction: Oh Manchester, so much to answer for…

Chelsea announced their financial results recently, and since then manager Antonio Conte has been muttering about not being able to compete in the football transfer and wages markets with the two big Manchester clubs. Is this true, and what are the state of Chelsea’s finances? Time to take a peek.

On the face of it, being Premier League Champions in 2017, progress through the group stages of the Champions League, semi-finalists in the League Cup and presently in the FA Cup, you would think there would be plenty to cheer about.

Income

Clubs have three sources of income. In 2016/17 Chelsea’s total income rose by 9.8% to £361 million, which is impressive given the club did not have the benefit of qualifying for European competition. As always, the devil is in the detail.

The increase in income of £32 million is behind that of both United (£66 million) and City (£82 million). Even Arsenal managed an increase of £70 million. So, it appears that Chelsea are struggling to keep up with the other ‘big’ clubs (Liverpool have yet to announce their results, and Spurs, who have not won the title in over 50 years, don’t really compete with the clubs already mentioned financially).

If we extend this growth comparisons over five years, Conte’s comments appear to have greater validity.

Clubs generate income from three sources, matchday, broadcast and commercial, so how have Chelsea performed?

Matchday

After four years of static matchday income, due to Stamford Bridge being at capacity every match and no price increases, there was a 9.4% fall in 2016/17. This was due to a lack of European competition, which usually would generate a minimum of three home matches.

At £65m, Chelsea’s matchday income is the third highest in the Premier League, but may have been overtaken by Liverpool (who had £62m in 2016). The gap between Chelsea and the two clubs above them shows the urgent need for a new stadium with increased capacity. If the rumours are true and the stadium will have 28% of seats sold to the prawn sandwich brigade this could catapult Chelsea easily into the £100 million a season club for this type of income.

Broadcasting

Broadcasting income was up 14% and tops £150m for the first time. This is due to the impact of the new domestic TV deal with BT/Sky. Chelsea’s UEFA TV monies were €69 million the previous season when the club was eliminated in the last 16. They should make at least that sum this season, as they earn extra due to being English Champions, although, due to the complicated formula used to determine UEFA payouts, will be hoping that the other English clubs are knocked out of the competition as quickly as possible.

The failure to qualify for Europe in 2016/17 put Chelsea at a £30-40 million disadvantage, enough to cover Alexei Sanchez’s wages and amortisation cost in the profit and loss account for a year.

Commercial

Chelsea’s commercial income grew by a solid 14% to £133 million. This seems good enough, but it pales compared to the peer group mentioned by Conte.

Whilst Chelsea have done well to increase their income by over £50 million in five years, they started off far behind United and City, and have fallen further behind. All clubs struggle to compete with United for sponsor appeal.

Intuitively Chelsea might expect their commercial income to be on a par with that of City. The reason why it is not normally elicits a call to the North London branch of The Samaritans from a man with a French accent, muttering something about ‘financial doping’.

This issue has implications for financial fair play too, as clubs are limited a £7 million increase in wages each year, plus any money generated by matchday, commercial income and gains on player sales.

Chelsea managed to extend their sponsorship income in 2016/17 by finding a separate sponsor for their training kit, a trick first spotted by Manchester United a few seasons ago.

The club may have had penalty clauses activated by some sponsors, and will have lost out in terms of perimeter advertising, due to the lack of European football.

Costs

The main costs for a club are player wages and player amortisation (transfer fee costs spread over the life of the contract).

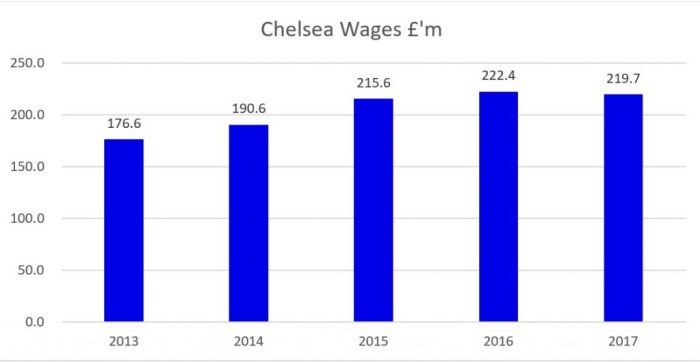

Wage costs fell for Chelsea in 2016/17. The club will have had to pay out win bonuses for lifting the Premier League trophy, but against that there will have been no match fees for Champions League fixtures, and some big earners (such as Mourinho J.) were no longer on the payroll.

Wage control in most industries is usually applauded, but football is not most industries. In the rarefied market for elite players, wages usually rise every time there is a new TV deal, as the Alan Sugar ‘prune juice’ impact is applied, Chelsea’s figures are at odds with this viewpoint.

Other clubs have increased their wages over the last five years. Chelsea were on a par with both Manchester United and Arsenal five years ago, but United have spent big, as shown the sums they have paid to the likes of Ibrahomovic, Pogba and Sanchez. United’s wage bill has increased by nearly £80 million over this period compared to just £43 million for Chelsea.

The other cost is that of amortisation, which is how a club expenses players signed in the profit and loss account. When N’Golo Kante signed for Chelsea in summer 2016 from Leicester for £30 million on a five-year contract, this works out as an amortisation cost of £6 million (30/5) per year. Chelsea’s total amortisation charge for the whole squad in 2016/17 was just under £90 million, an increase of 25% on the previous season. It’s high by Premier League standards (the average was £35 million in 2016), but significantly lower than the Manchester clubs.

Adding both wages and amortisation together gives the total football player cost for the season.

United and City are neck and neck, Chelsea are about £75 million a season behind.

One common metric used to look at the effectiveness of player cost control is to compare wages (or wages and amortisation) as a percentage of total income. The lower the percentage, the more effective the control, and the greater the scope for future investment in players.

The above reveal that Chelsea presently have the poorest wage control of its peer group, and Manchester United, as resented as they are by fans of other clubs, run the tightest ship. If you factor in what United have paid to banks over the years in interest payments though, it’s advantage over the other clubs is eroded.

Profit

Profit is an abstract concept, in theory it should simply be income less costs. In practice there are a range of profits quoted, depending on which costs are included.

Chelsea in their press release stated a profit of £15.3 million for 2016/17. This is however after considering gains on player disposals, including that of Oscar. These gains totalled £69.2 million.

Whilst we expect to see clubs making a profit on player sales each year due to the way player signings are treated in the accounts, this figure is volatile as it depends on individual player disposals.

Excluding player disposals, Chelsea’s EBIT (which is ‘recurring’ profit before interest and tax) was a loss of £53.4 million, slightly higher than £46.2 million the previous season.

Adding back the non-cash expenses in the form of depreciation and amortisation gives an EBITDA profit of £46 million, which is over 30% higher that the previous year’s £35.1m.

Comparing to the peer group, United made an EBITDA profit of £200m, City £105 million and Arsenal £145m, reflecting that Chelsea are weaker than the other elite clubs in this regard.

All the elite clubs are well within FFP limits.

Player activity

Chelsea spent over £100 million on players in 2016/17, including Kante, Luiz, Batshuayi and Alonso. This is a major investment but isn’t keeping up with the noisy Mancunian (or as my mum likes to call them, Manchurian) neighbours at the top of the Premier League, it was even less than Arsenal spent in the same season.

In terms of disposals, Chelsea sold players for £98 million, to give a net spend for 2016/17 of £8m.

Hidden in the footnotes to the Chelsea accounts are a couple of interesting figures (interesting only to those who are still reading this tedious summary we suspect). The first is contingent liabilities.

This is the sum the club must pay to players and former clubs if certain achievements (appearances, trophies, international caps etc.) are met. This was £3 million and compares to £111 million for Manchester City and £45 million for United at the end of June 2017.

This suggests that Chelsea have a different approach to the two Manchester clubs when signing players, aiming for a set fee with little based on future performance.

Chelsea had a spending spree in Summer 2017, mainly on signing Morata, Bakayoko, Drinkwater, Rudiger and Zappacosta for £212 million, which suggests that Antonio Conte’s comments were perhaps wide of the mark. A number of players left the club too, bringing in £63 million.

Summary

Roman Abramovic these days seems to want to make Chelsea break even financially, but that will be insufficient if he also wants to win trophies such as the Premier and Champions League.

The proposed stadium is essential if Chelsea are going to compete in terms of income against the two Manchester clubs, but its going to be a few years before the constraints of playing at Stamford Bridge are overcome.

Conte’s comments (which are echoed to a degree by Arsene Wenger) do appear valid. Chelsea cannot compete with the two Manchester clubs as they cannot match them in terms of income, which in terms gives the ability to pay wages and sign players…unless Abramovic decides to pursue a more expansive strategy. He’s already sunk over a billion into the club, but it may take almost as much again to fund a new stadium.

Data Set