Brighton 2018/19: Switch

Introduction

A lot of money is required to get to the Premier League, but as the 2018/19 Brighton and Hove Albion accounts reveal, it takes a lot to stay there too.

Losses of £21 million were announced for the year to 30 June 2019, reversing a profit of £12 million the previous season as the club finished in 17th position in the table.

Investment in players was the main reason for the deterioration in the financial results, as well as some one off costs following Chris Hughton’s sacking the day after the season ended.

Income

Just ten years ago Brighton’s income was £5 million for the whole season, but this had increased to £143 million by 2019.

A football club generates income from three main sources, matchday, commercial and broadcasting.

Having sold out matches at the Amex for the club’s two seasons in the Premier League matchday income was static in 2018/19.

A club can only increase matchday income by increasing prices, capacity or the number of events that take place at the stadium.

No league attendances fell below 29,600 last season as the club sold out most home matches at the Amex stadium and whilst there were three cup matches at home these were at discounted prices so had little impact on total matchday revenue.

Brighton’s matchday income put it 12th in the Premier League table (note figures are for 2017/18 for most clubs as they haven’t yet published their accounts) which is intuitively higher than you might expect with the club being above the likes of Everton and Leicester.

A look at the small print of club accounts however reveals that some clubs treat the likes of merchandise and hospitality boxes as matchday income and others as commercial, which makes a 100% accurate comparison impossible.

Keeping attendances at close to capacity is a tricky exercise and means that Brighton cannot increase ticket prices too aggressively in case fans revolt.

Sponsorship income mainly comes from American Express and Nike for Brighton and this increased by 7% in 2018/19 but should accelerate due to a revised Amex deal worth an estimated £100 million over the next decade compared to £1.5m a year at present.

Half the clubs in the Premier League have gambling companies as sponsors who historically have paid more than other industries for the non ‘Big Six’ clubs but Brighton seem to have bucked the trend by aiming for a long term relationship with American Express which seems to have paid off.

Income from broadcasting is the main source for non Big-Six teams and Brighton are no exception and last year benefitted from an improved Premier League overseas deal plus an FA Cup run to the semi finals.

Seventeenth position in the Premier League meant that Brighton earned £4m less from the prize pot but this was offset by the other issues, meaning that almost four pounds in every five came from broadcasting.

Total income for Brighton was therefore a record £143 million, but this was not sufficient to prevent them losing money last season and still puts them in the bottom half of Premier League clubs.

Player Costs

Having been promoted in 2017 Brighton’s costs in their first season in the Premier League increased more slowly than income, allowing the club to make a profit, but this benefit reversed last season as Sir Alan Sugar’s ‘prune juice’ comment was evident and wages absorbed more and more revenue.

Every fan knows that player costs are the most significant expense for a football club and this is the main reason why Brighton lost money in 2018/19.

Player’s wages were the main driver of the bill increasing by over 30% to £101 million last season, as new contracts for Dunk, Duffy and Gross, plus the signing of Jahanbaksh, Bernardo, Montoya, Andone, Burn, Bissouma, Button, MacAllister, Tau and others came in with Premier League wage expectations.

Even so, Brighton’s total wage bill is still relatively modest by Premier League standards, and the total cost for the season for all 20 clubs could top £3 billion for 2018/19 once all the remaining clubs publish their accounts.

Relative to every £100 in income Brighton paid out in £71 wages last season, UEFA have a ‘red line’ of £70 although this is far lower than the majority of their time in the Championship.

Some fans may remember Brighton’s first season in the top division in 1979/80 wheret the wage bill for all whole staff was £785,000, equivalent to what the average Brighton first team player earned last season in four months.

In the content of the Premier League as a whole Brighton’s wages are still quite modest, partly as a legacy of being relatively recently promoted and this puts them in the main bunch of provincial clubs in the division.

Amortisation is the other player expense, which is calculated as transfer fees spread over contract life, so the signing of Ali Jahanbaksh for £16 million on a five-year deal works out as an annual amortisation cost of £3.2 million (unless you’re Derby County, in which case it is mysteriously lower).

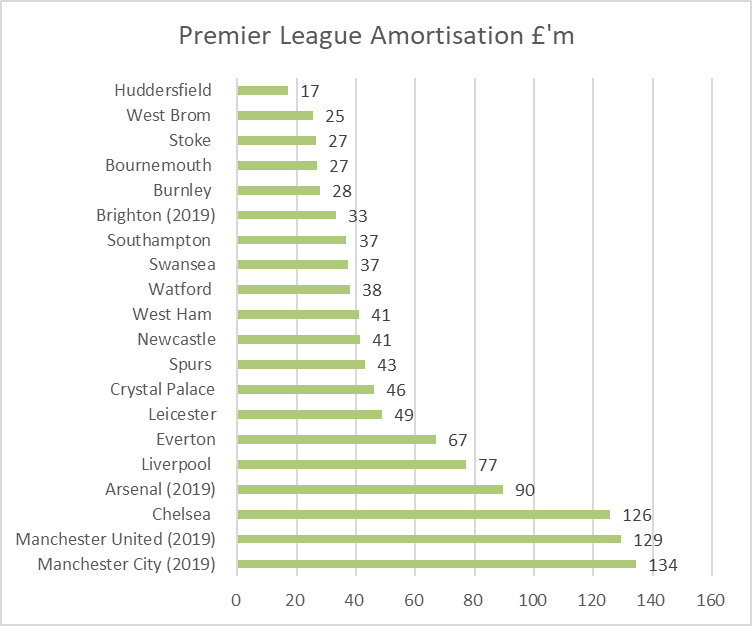

Nevertheless, despite the amortisation charge increasing by 500% since promotion in 2017 Brighton’s total of £33m again places them, as you would expect from a squad that still has a number of Championship and academy/youth signings, towards the bottom of the Premier League table in regards to this expense category.

Profits/(Losses)

Profit (and losses) are calculated as income less costs and Brighton’s pre-tax loss of £22 million may have surprised some but the figure was impacted by the cost of sacking Chris Hughton and paying compensation to Swansea for Graham Potter.

‘Exceptional’ items as the above management changes are called are usually set out in detail by Premier League clubs (such as Manchester United sacking Mourinho for £19.6m and Arsenal having £3.1m in their 2018/19 accounts too) but Brighton are notoriously coy when it comes to disclosures and have frustratingly not disclosed any details here.

Losses would have been higher had it not been for selling some fringe players which generated modest profits, without these Brighton’s losses would have been £24.6 million.

Everton made the highest losses in the Premier League of over £1 million a week in 2018 and what may surprise many is that only a Norfolk handful of clubs made a profit, relying on owner bailouts and player sales to cover the losses.

Player trading

Brighton’s singings detailed above cost a combined £78 million in 2018/19 although their impact on the pitch can best be described as ‘mixed’ none of them made a huge impact on the pitch. This took the total cost of the squad to £152 million.

In the summer 2019 window Brighton bought Maupay, Webster, Trossard and Clarke, but again, unlike most Premier League clubs, frustratingly didn’t disclose the gross or net spend in the window.

Funding

Brighton have been dependent upon owner Tony Bloom for over a decade. He originally was providing money for signings (such as Glenn Murray from Rochdale in 2007 for £300k) behind the scenes but since becoming chairman has underwritten the cost of the stadium, training ground and operational losses to a total of £352 million.

This investment is split between interest free loans and shares, and 2018/19 was no exception as he lent the club a further £49 million to provide funds for further infrastructure and player spending.

Whilst no doubt Bloom wants the club to be self sufficient at some point, at present his benevolence has advanced the club from the wrong end of League One to a third season in the Premier League. More investment may be required if his stated aim of a regular top ten place in the Premier League is achieved.

Summary

So, where does this leave Brighton? The achievement of getting to and staying in the Premier League had worn off for both fans and owner last season as Chris Hughton’s pragmatic but unlovable football during the second half of the season ultimately led to his dismissal.

The club still needs time to establish itself in the Premier League and no doubt has seen how the likes of Sunderland, Middlesbrough and Stoke have struggled when relegated to the Championship.

Fans have been impressed with the style of football under new manager Graham Potter, but with a very compacted middle part of the table two or three consecutive wins or defeats can have a club such as Brighton eyeing up Europa Cup or relegation spots.

The losses made by Brighton last seaon do perhaps suggest that those who think that buying a club in the Championship or League One and underwriting losses to get to the Premier League are probably chasing fool’s gold.

Brighton are fortunate to have an owner in Tony Bloom who has a strategy for the club and as such is unlikely to indulge in some of the madcap short term schemes that have left many in the EFL looking very vulnerable. Those club owners gambling on selling stadia, unusual sponsorship deals and creative accounting are taking a huge risk.