Brighton 2017/18: What Do I Get?

Introduction:

Tony Bloom, Brighton’s owner, probably heaved a sigh of relief in 2017/18, not just because his team had been promoted, but for the first time in living memory the club made a profit.

Over the six initial seasons that Brighton had played in the Championship at the Amex stadium, the Albion had lost £110 million.

Nevertheless, Bloom still ended up lending the club £32 million in 2017/18 as he underwrote investment in new players and capital projects.

Yet for some Brighton fans this benevolence from Bloom is not enough, and recent tantrums and whines on social media suggest that some fans will always want more, especially if someone else if footing the bill.

Key figures for year to 31 May 2018: Brighton and Hove Albion Holdings Limited

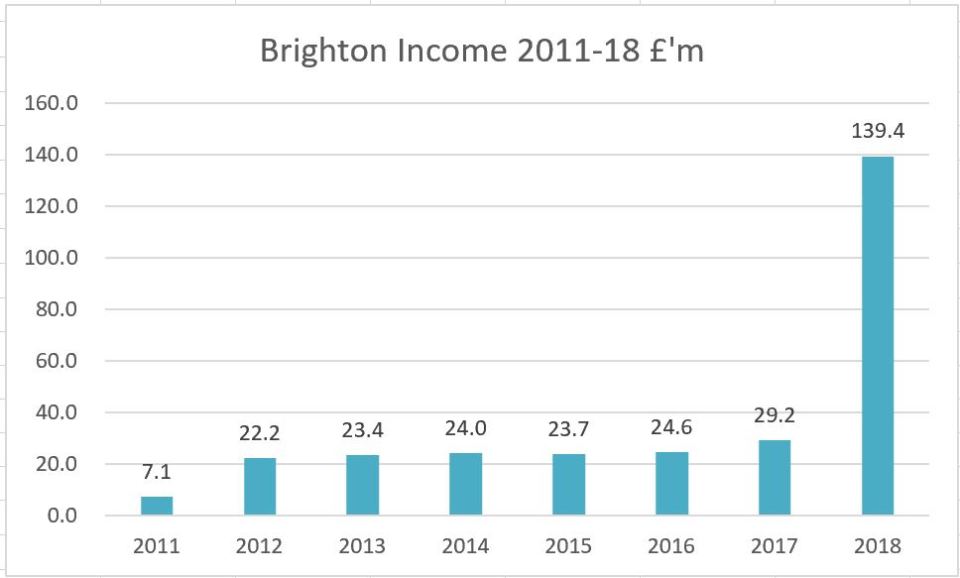

Income £139.4 million (up 378%).

Wages £77.6 million (up 148%) .

Operating profit £12.8 million (previous year loss of £38.9 million)

Player signings £57.5 million

Player sales £3.5 million

Tony Bloom investment £318 million (up £32 million).

Income:

Brighton, like all clubs generate money from three main sources, matchday, broadcasting and commercial, and whilst the figures for 2017/18 were a record for the club, they are still relatively low compared to those clubs who are regularly competing in European competitions and have global fanbases.

Love it or loathe it, broadcasting income is the main driver of income for a club such as the Albion, and the difference between clubs in the EFL and the EPL is part of the reason why clubs in the Championship are losing nearly £400 million a season as they seek the end of the rainbow in the division above.

Overseas and domestic broadcasters are prepared to pay top prices for Premier League rights at they have discovered that this is the one product that minimises viewers cancelling their subscriptions.

Only a quarter of Brighton’s income came from TV in the Championship, but this rose to four-fifths in the Premier League, and some clubs are even more exposed to this income source.

Many critics of the Premier League claim that broadcast income levels are a bubble and will burst, bankrupting clubs who are dependent upon it in the process, but there is little evidence to support the view that we are near the end of the road for the likes of BT and Sky paying billions to cover the game live.

Selling TV rights at a loss when the Premier League was started in 1992/3 had proved to be a masterstroke, as the value of those rights has subsequently increased to about a billion pounds a year.

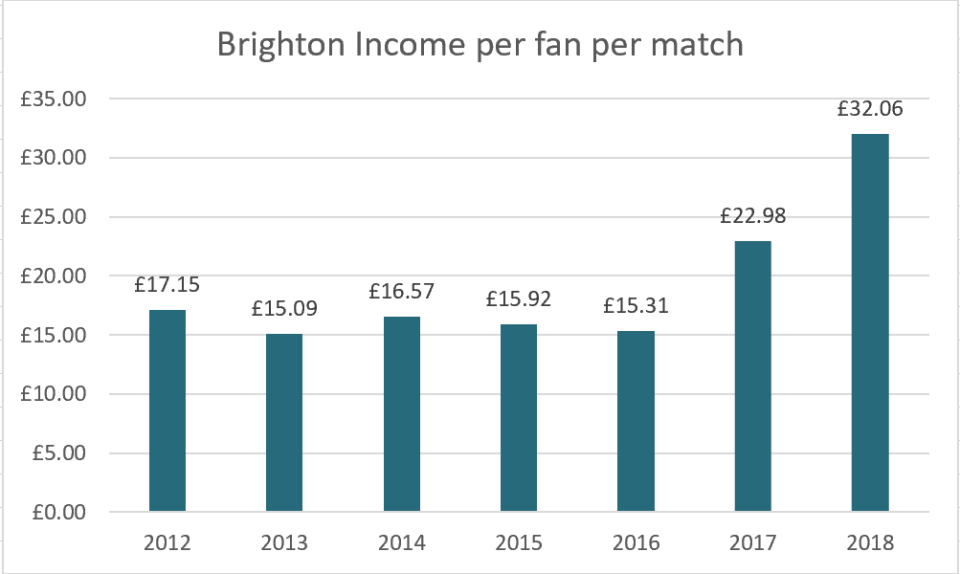

Brighton’s matchday income rose substantially in 2017/18, although we suspect that part of the increase is due to changing what is included in the split of matchday and commercial income totals.

Less fixtures in the division would in theory result in less income, but a combination of increased average attendances (up from 27,966 to 30,403) and higher matchday prices led to a 25% increase.

Unlike most other clubs, Brighton’s ticketing policy includes subsidised travel to and from the Amex stadium for those that want it, so a direct comparison with clubs of a similar ground capacity is not entirely valid.

Even so, Brighton generated more matchday income than the likes of Leicester, who won the Premier League in 2016, and had £10m more from this source than half a dozen competitors, and this was partially due to the club’s ability to monetise the fanbase compared to previous years.

As a newcomer to the division, Brighton were slightly constrained by existing commercial deals, and according to Nick Harris’s excellent SportingIntelligence website have a very low value shirt sponsorship arrangement with American Express compared to the going rate for the Premier League.

Nevertheless, commercial income rose by a quarter to over £10 million, but the club is a pauper compared to the riches earned by the self-styled ‘Big Six’.

Despite the relative lack of commercial income, Brighton have fared reasonably well in the Premier League overall, finishing 12th in our initial total income table, although this may change as more clubs announce their 2018 results.

What is likely to be the biggest driver of income change for 2018/19 is the club’s final league position, as this is worth £1.9 million for every extra place in the league that the club finishes.

What is likely to be the biggest driver of income change for 2018/19 is the club’s final league position, as this is worth £1.9 million for every extra place in the league that the club finishes.

Costs:

Having a place in the Premier League means that expenses rise too, and the main drivers here relate to players, in the form of wages and transfer fee amortisation.

Increasing a wage bill by nearly 150% would be considered madness in most industries, but football is like no other, and to compete the club has had to pay the going rates.

There were new contracts given to some of the players central to Brighton being promoted from the Championship in 2016.17, such as Dunk, Duffy, Stephens, Knockaert and Bruno, as well as new signings joining the club whose agents have a rough idea of the going rate for the division.

Even so, wages rose slower than income, and this resulted in Brighton’s wage/income percentage nearly halving, as the club paid out £56 in wages for every £100 in income, comapred to £107 the previous season (and there were substantial promotion bonuses paid out on top of this sum too).

As a rule of thumb Premier League clubs are usually deemed to be running well if the wage to income ratio is below 60%, so Brighton have achieved this objective in their first season.

Relative to their peer group, Brighton seem to have wages under control and have not thrown money at the issue of avoiding relegation.

Married to the cost of player wages is the transfer fee amortisation expense, which arises when a player signs for a club and the accountants spread the transfer fee over the contract life.

Yearly amortisation fees represent a less volatile measure of a club’s transfer policy, which can be distorted by big purchases in one year followed by a period of relative austerity, and so give a better long-term guide to investment in the playing squad.

Brighton’s amortisation cost for the year more than tripled, as the club broke its transfer record many times on Ryan, Propper, Izquierdo, and Locadia over the course of the season. Therefore, when Davy Propper signed for an estimated £10 million on a four-year contract, this works out as an amortisation charge of £2.5 million a year.

By Premier League standards the amortisation cost is relatively low, reflecting that the club is in its first year in the division and has also kept faith with players recruited at Championship prices and therefore lower amortisation fees.

Directors’ pay

It was not just the players who benefitted from Brighton’s promotion. CEO Paul Barber saw his pay package increase to over £1.4 million, reflecting the faith that Tony Bloom has in him and the fact that he was coveted by other clubs in the division, such as Liverpool.

Barber attracts some hysterical reactions from sections of the Brighton fanbase, who seem to think he is the spawn of Beelzebub. His email replies to fan complaints are legendary in length, and whilst his dedication to communication is to be commended in many regards, when fans want nothing but appeasement for the personal slights that they take when some decisions are made, he may struggle to make much headway with their views. Every village has an idiot, and there are a lot of villages in Sussex, all of whom seem to enjoy writing letters of complaint to the Brighton CEO.

The Premier League is a law to itself when it comes to executive pay, there seems to be little indication of what is the going rate, and some of the figures quoted, especially for clubs that purport to give no money to the big cheeses, are best described as ‘unusual’ but are likely to get the investigative journalists at Der Spiegel busy going through leaked emails.

Profits and Losses

Profits/losses are income less costs, and the headline figure for Brighton was a £12.8 million last season, or £350,000 a week. This figure is distorted by a couple of factors though.

Whilst the club kept the vast majority of the squad from the Championship, a few players were sold and this generated profits of £3.4 million, The nature of player sales profits is that all of the profit is shown in the year of sales (unlike player purchases which are spread over the contract) and so create erratic and unpredictable figure.

In 2016/17 the club paid out £9.1 million in promotion bonuses, as Tony Bloom rewarded all employees at the club, not just the playing staff, for taking the Albion to the top flight. Such bonuses distorted the results for that season as they are non-recurring in nature.

Stripping out the above two distortions gives something called EBIT (earnings before interest and tax) profit, which is a more balanced look at what recurring profits would be.

This shows the alarming state of trying to compete in the Championship and gives a more nuanced measure of the benefits of promotion, which are effectively £40 million comparing 2018 to 2017.It also reinforces the view that Brighton would have had to cut back significantly in the playing squad by selling players had they not been promoted the previous season to comply with EFL FFP.

Player trading:

According to the accounts Brighton spent over £57 million in 2017/18 on player signings, a club record. This doesn’t necessarily buy you a lot in the present Premier League market though.

Compared to their peer group, Brighton’s spending was reasonable but unspectacular.

Since the end of the season the board have backed Chris Hughton, with another £50-60 million being spent on new signings.

Funding the club

Tony Bloom’s total investment increase in 2017/18 as he lent the club £32 million. These loans realistically stand little chance of being repaid under present circumstances unless the club starts to make significantly higher profits, although there is little sign of Bloom wanting his money returned. The good news is that the loans, unlike some from directors at Premier League clubs, are interest free.

Whilst fans may scratch their heads at how he had to lend the club money in a year when it made a profit, Bloom repaid the Albion’s overdraft at Barclays Bank (£16 million at start of season), only a fraction of the cost of new players was reflected in the amortisation charge, and the club also spent nearly £10 million in upgrading the Amex stadium and other infrastructure projects.

This takes his total investment to £318 million, in the form of shares and loans.

Conclusion

Brighton’s approach under Bloom of concentrating on the infrastructure first (stadium and training facilities, followed by squad investment) paid dividends in 2017 and the club was able to capitalise with a solid if unspectacular first season in the Premier League.

With the fifth lowest wage budget in the division, a relegation scrap is going to be the order of the day for a few seasons, but provided Bloom keeps his nerve and faith in Chris Hughton, then there is a fair chance of making some progress.

Whether the pitch fork element of the fan base has such patience (and they are not the ones who were subsidising the club for tens of millions in the Championship) is another matter.

2 Comments

Aelred Wilkinson

That is an excellent read. When I speak to fellow fans we are all realistic about where we are and how much we owe to Uncle Tony. Perhaps I don’t know any village idiots. These are the great days for our club. Cheers. And Up The Albion.

Seagulleo

Pulling no punches on fan expectations. In reality, this is a very small proportion of fans. The vast majority recognise Tony’s unbelievable financial and emotional ongoing commitment. Paul’s competence is also widely acknowledged, even if the way he communicates it can betray a tin ear at times.

Twas ever thus. The Brighton crowd can be fantastic. At times, they can also be demanding and unrealistic. Be careful what you wish for!