Bournemouth 2016/17 and FFP Fine: Every Breath You Take

Introduction:

Bournemouth have just agreed a fine of £4.75 million with the English Football League in relation to a breach of FFP rules, a couple of years after initially showing an expected fine of £7.615million, so we thought we’d take a more detailed look at how this arose and the state of the Cherries’ finances.

Overview

Income £136.5 million for 11 months to 30 June 2017 (2016 £87.9 million for year to 31 July 2016)

Proportion of income from broadcasting 91% (2016 85%)

Wages £71.5 million (£59.6m)

Profit before player sales £15.2million (loss £6.1m)

Highest paid director £1,226,000 (£1,074,000)

Player signings £9.3 million (£69.8m)

League position 9th (16th)

Income

For reasons best known to themselves, Bournemouth chose to reduce their accounting period to 11 months. Lots of clubs mess around doing similar issues (Manchester City, for example, had 13 months for 2016/17). It makes our job a wee bit harder, but we will try and compare on a twelve month basis when calculating percentages.

Clubs generate income from three main sources, broadcasting, matchday and commercial. Bournemouth, constrained by the 11,000 capacity of their stadium, are more reliant than most clubs on one source.

Broadcasting income:

Bournemouth benefited from a record finish in the Premier League of 9th, compared to 16th the previous season. This earned them an extra £13.3million in prize money to £124.2 million, as the TV riches are partially split on final league position. In 2017/18 they ‘only’ earned £111.2 million as they finished 12th (and appeared on TV less often too).

Bournemouth also benefitted from the first year of a new three-year domestic broadcast deal from BT and Sky, which increased the total money earned by the English Premier League (EPL) by about £700 million.

The big gap between the ‘Big Six’ clubs (although this season joined by Leicester) and the rest is because in addition to the broadcast money from EPL participation, they also earn money from UEFA tournaments. Leicester pocketed £72 million from their progress in the Champions League.

The combination of a higher league finish, higher overall broadcasting rights and a small stadium meant that Bournemouth became the first team in the history of the Premier League to earn more than 90% of their income from this source, with £90.99 in every £100 coming from broadcasting.

Matchday Income

Matchday income is number of tickets sold per match x average ticket price. Here Bournemouth are at a disadvantage.

Average attendances for 2016/17 were 11,182, effectively identical to the previous season. Whilst every match was a sellout, the capacity of the Vitality Stadium (Dean Court to you and me) of 11,360 meant the club was always going to struggle to compete against other clubs in this regard.

It will therefore come as no surprise that AFCB had the lowest matchday income of any club in the division.

Matchday income generated £605.6 million for Premier League clubs in 2016/17, but Bournemouth’s share was only 0.85% of the total.

Bournemouth’s matchday income actually fell in 2016/17 by 4.2%, mainly due to the cap on ticket prices for away fans, and less progress in cup competitions.

Bournemouth generated £456 per fan from matchday income in 2016/17, about mid-table, and this works out as just over £22 per match to watch the team, which is considerably lower than some of the ‘glamour’ clubs in the division who have a far larger proportion of prawn sandwich eating fans.

Commercial income.

Whilst commercial income fell by 10%, this was mainly due to the accounting period being only 11 months long compared to 12 the previous season.

The club have realistically gone as far as they can go from this income source until they move to new premises.

The club have the second lowest level of income from this source, only beating that of the Premier League’s most boring club (from a sponsor perspective), Watford.

Such is the dominance of broadcast income though, that despite being in the relegation places for matchday and commercial revenues, Bournemouth had the 13th highest overall income in the division. They may even have overtaken West Brom had they produced a twelve month set of accounts.

A look at the club’s income for 2014/15, the year they were subject to the EFL FFP fine, shows income of only £12.9 million for the season, which was the sixth lowest in the division.

Costs

The main costs for any football club are player related, and are split between wages and amortisation.

Bournemouth’s wage bill for 2016/17 was £71.5 million for 11 months, which works out as a 22% increase on an annualised basis.

Bournemouth’s wages on an annualised basis are still some of the lowest in the division, which reflects the club’s policy of not being held to ransom by player demands, as evidenced by Matt Ritchie being allowed to leave to go to Championship Newcastle, who offered him a shedload more money.

The club presently have good control over wages, paying out just £52.42 in wages for every £100 of income, which is lower than the Premier League average.

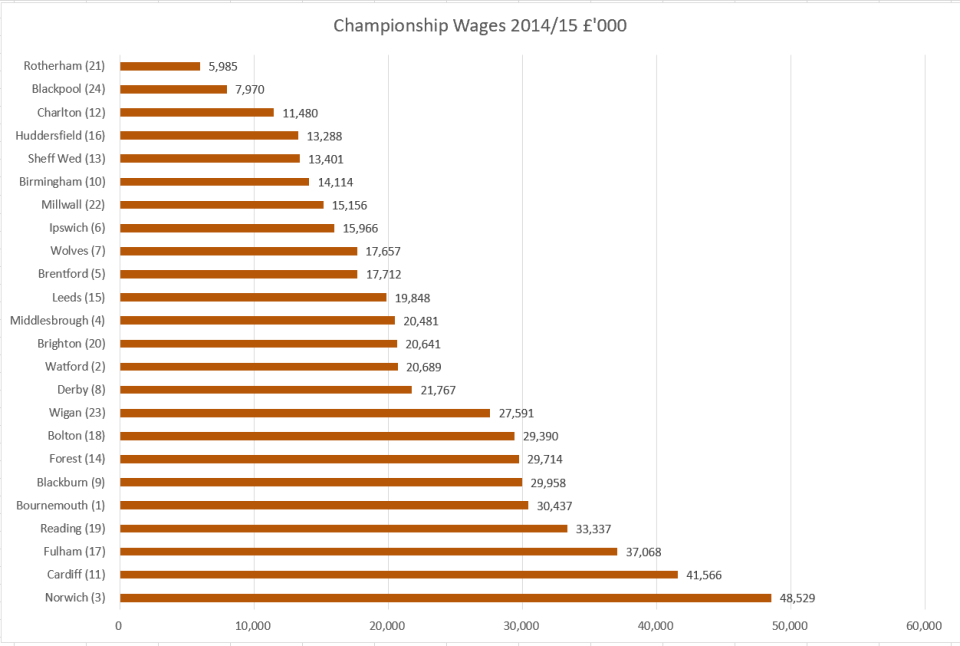

The issue in relation to the EFL fine arose when the club was in the Championship in 2014/15, with a £30.4 million wage bill. This meant that Bournemouth spent £237 in wages for every £100 in income, which on the face of things blew a whole in the club’s FFP compliance.

This was a far higher proportion of income than any other club, although the Championship is a notoriously unruly division, with the wage bill regularly equalling or exceeding total income.

On an actual wage bill basis, AFCB were not at the top of the table, as clubs with parachute payments from the Premier League were able to bear larger contracts.

Bournemouth did however have the largest wage bill for clubs not in receipt of parachute payments, just ahead of Forest (who also had FFP sanctions as a result). Bournemouth did not break out how much of their wage bill that season was in respect of promotion bonuses to staff. This is important for FFP purposes, as promotion costs are excluded.

Looking at other clubs who have gone up in recent years though, we would expect the promotion costs to be in the region of £9 million, which brings Bournemouth’s recurring/sustainable wage bill down to about £21 million. This is still considerably higher than the club’s income, but not excessive by Championship standards.

The executives of Bournemouth have also done well as a result of promotion.

Compared to where they were in League One, the highest paid director at the club has had a 542% pay rise in the last five years…which is nice.

The other player related cost is amortisation. This arises when a club pays a transfer fee, which is then spread over the contract length in the profit and loss account. Therefore when Bournemouth signed Benik Afobe from Wolves in January 2016 for £10 million on a 4½ year contract, this works out as an annual amortisation cost of £2.22 million a year (£10m/4.5).

Bournemouth’s amortisation expense has increased as you would expect since the club moved from League 1 to the Premier League since 2013.

In the context of the Premier League, Bournemouth are where you would expect them to be, even adjusting for their 11 month accounting period. Relative low spenders along with a spine of a team from the lower leagues means they are close to the bottom of the table.

One thing that is mysterious in relation to Bournemouth’s accounts is the heading ‘other costs’. This increased by

This has increased by nearly 50% compared to the previous season in the Premier League, but the club give no clue as to what makes up this figure.

Profits

Profits are income less costs. There are a variety of different means of determining profits, many of which are tainted by the dark arts of accountancy.

The club announced in the strategic report an operating profit of £16.1 million, compared to £5 million the previous season. Operating profit is total income less total costs of running the club except loan interest and tax.

The only problem with such a figure is it contains some items which are either volatile from one year to another (such as gains on player sales) and others which are one-offs (such as FFP fines).

We therefore prefer to use something called normalised EBIT (Earnings Before Interest and Tax) which adjusts for the above items.

This profit measure shows that Bournemouth had their most successful year in the club’s history in 2016/17, mainly on the back of the increased broadcasting revenues. It also highlights the issue that has occupied those who snipe at the club in terms of the losses made in 2014/15 when the club was promoted to the Premier League and the FFP fine arose.

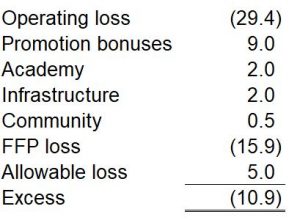

FFP profit is however a law unto itself. In 2014/15 clubs were allowed a maximum FFP loss of £6 million. Some costs are excluded from FFP, such as infrastructure (£2m in 2015), promotion bonuses (estimated £9m), academy (£2m est.) and community schemes (£0.6m est).

If these costs are added back to the operating loss then we arrive at the following estimate of an FFP loss.

Under EFL rules clubs promoted are subject to an FFP fine (as a transfer embargo is not feasible when clubs move to the EPL), which is calculated on a sliding scale as follows:

This gives an FFP fine estimate which is in within a gnat’s testicle difference from the figure shown in the Bournemouth accounts for 2014/15 of £7.615 million.

To give Bournemouth credit the club held its hand up, admitted that it had exceeded the allowable profits and set aside a sum (but did not appear to pay) the sum in the accounts.

Enter two flies in the ointment, both Queen’s Park Rangers (from 2013/14) and Leicester City (2014/15) were also subject to EFL potential fines when promoted. They took a different approach to Bournemouth and instead tried to claim that FFP was illegal and therefore fines unenforceable. Bournemouth therefore awaited how these two clubs were dealt with before handing over the money, and to an extent that seems a fair approach to take.

The fact that they knew the FFP rules whilst members of the Championship appeared to have bypassed the clubs’ respective owners. QPR have a potential fine of about £40 million from the season in which their income was £38 million and wages were £73 million, resulting in a loss of £65 million. Since then their lawyers, esteemed London firm Cockwomble, Wankpuffin and Co, have used every wriggling, prevaricating and filibustering scheme known to man to try to weasel out of paying the sum due.

Our snouts close to the EFL advise that the League became so paranoid about the constant stream of queries, points of order and delaying tactics from Cockwomble, Wankpuffin and Co that whenever QPR was discussed at EFL meetings it was agreed that no notes would be included in the minutes of the meetings to try to reduce the ambulance chasers from finding yet another excuse to push back judgement day. Even though the case went to arbitration in 2017 and QPR lost, there has been an appeal to further drag out the outcome (whilst of course the lawyers have their meters still ticking, and Range Rover Sport brochures are looking decidedly thumbed).

Leicester agreed to a fine of £3.1 million in February this year, after their lawyers Sue, Grabbit and Runne advised the club to reach a settlement. It is probably on the basis of the calculations and appeal used by Leicester that Bournemouth have managed to have their FFP fine reduced from £7.6m to £4.8m.

Our view here at Price of Football towers has been unchanged since FFP was first introduced. It discriminates against smaller clubs (such as Bournemouth) who have less ground capacity than others and also against all clubs that are not in receipt of parachute payments.

FFP also encourages clubs to get creative with their accounting policies (see our blog on Derby County if you fancy the tedious details) as compliant auditors with the spines of jellyfish and legal firms (and yes we know there are good ones too) with the moral compass of Gary Glitter in a flooded cave full of Thai schoolboys see FFP as an opportunity to fill their boots with fees.

As such we think that the rules are a waste of space in the Championship, where EBIT losses in 2016/17 were a staggering £392,000,000…and that is with FFP in place.

Player Trading

Rant over, and back to The Cherries. Bournemouth have been relatively cautious in the transfer market compared to their peers, but still spent record levels by the club’s own standards.

The club did have a spending spree in the first season in the Premier League, but care should be taken when looking at the 2016/17 figures, as by reducing the club’s year end from 31st July to 30th June to “align internal financial reporting dates with the financial year”, which is management-speak for complete and utter bollocks, it also meant that player signed in July 2017, which is a major period in the transfer window, were effectively excluded from the numbers.

In the small print to the accounts it does reveal that the club spent a further £39.8 million on players before the accounts were signed off.

In the year they were promoted, transfer spending of £13.2 million was not excessive in a division that spent a total of £157 million on players that season.

The only slight concern is that a lot of the transfer purchases appear to be on instalments, which might cause problems should the club fall out of the Premier League. At 30 June 2017 the club owed £22.8 million for transfers, and remember this is before they spent money the following month in the window.

Ownership

AFCB’s owner, Maxim Demin, remains a mystery. He’s certainly put his hand in his pocket and loaned the club about £35 million. Demin’s ownership is via a company called A.F.C.B Enterprises in the British Virgin Islands (nothing to do with Virgin boss Richard Branson, or, for thinking about, the country’s most well known non-virgin connected to football, Katie Price).

The club’s other shareholder, US based Peak6 Football Holdings are owed a further £19 million. Both these loans are interest free, unlike those of the battery powered device salesmen at West Ham, who have charged the club over £14 million in interest since they took over the club.

Demin’s motives are unclear, but whilst he continues to support the club, and is keen to allow it to expand via a stadium expansion, fans probably don’t care too much.

Conclusion

Bournemouth generate a lot of resentment, and we think that most of it is fairly harsh. Thunderbird pilot lookalike manager Eddie Howe is fairly inoffensive, if a bit of a media darling, but the claims that the club somehow cheated their way to promotion in 2014/15 are excessive and unwarranted.

They were fairly open about their ambitions, and spent money well, unlike the approach taken by Aston Villa in 2016/17, who laid a trail of £50 notes to anyone who had a Panini Card collection and wanted to wear a claret and blue shirt, spunking a quite ridiculous £88 million on players that season.

Bournemouth were promoted to the Premier League because they played the best football in the division that season. Spending money a bit excessively by FFP purposes certainly helped their recruitment, but it didn’t give them a competitive advantage over many ‘bigger’ clubs in the division and those in receipt of parachute payments, it merely reduced the advantage those clubs had over The Cherries.

The biggest deceipt of FFP is that it makes fans think it is something to do with ‘fairness’ and that compliance with the rules is somehow egalitarian and honourable, but in reality its aim, especially at the higher levels of football, is there to lock in the differential between existing large and small clubs.

One Comment

Will Dance For Chocolate

Brilliant, thanks.

You’re right about the fans of clubs complaining about FFP and the promotion. It’s always those with big stadiums who resent that another club wanted to compete with them on a level playing field in terms of spend. They eulogized about it almost non-stop every time our name is mentioned since, carefully overlooking FFP is fair in the same way the People’s Democratic Republic of Korea is democratic. Rather than getting angry ar us they should instead reserve their ire for their own club who mismanaged a similar sum of money.