West Ham United 2017 Financial Results: Fool’s Gold

After an emotional farewell to the Boleyn Ground the previous season, West Ham moved to the London Stadium, and fans had high expectations that the club could start to chip away at the glass ceiling of the self-styled ‘Big 6’, who have a disproportionate share of the income, and therefore best players, within the Premier League.

Those hopes failed to materialise. A poor start in the Europa League, where they were knocked out before the group stage by the team that finished 6th in the Romanian League the previous season, was followed by problems with the new stadium in terms of logistics, stewarding and atmosphere. A spat with the council resulted in the capacity of the London Stadium being capped at 57,000.

In terms of finances, the boost from moving to a more modern stadium seems to have been a mirage in some ways, and fans are unhappy, losing their home is one thing, losing it and having no benefits is another.

Income

Clubs have three main sources of income, matchday, broadcast and commercial. In 2016/17 West Ham’s income rose by 29%, so it looks as if Sullivan and the Gold brothers (whom Claudio Ranieri apparently calls Dilly-Dee and Dilly-Do) had masterminded a superb transformation of the club. Over the last five years the club’s income has more than doubled, how much of this achievement is due to the owners, and how much is due to happenstance?

Matchday

Moving from a 35,000 to a 66,000 capacity stadium in theory should have created a big bump in matchday income, but the move only resulted in a 6% increase from £26.9m to £28.6m.

There are a number of possible issues in relation to this surprisingly low increase.

West Ham had a dispute with the landlord and licence holders of the London Stadium, which restricted capacity to ‘just’ 57,000, although this is still substantially higher than the Boleyn Ground.

Season ticket prices were available from £299, and Under-16’s just £99, which looks from afar as if the owners were using a combination of a new TV deal and higher attendances to make watching the club more affordable.

It could also be that the figures for the final season at the Boelyn were inflated by extra income generated in relation to moving from the stadium, as they are substantially higher than 2014/15.

Compared to other clubs in the Premier League who have reported to date, West Ham are stuck in the middle.

The above shows how many millions are generated by matchday income, and the proportion of total income from that source.

Matchday is worth £1 in every £6 of total income to West Ham.

If the club are serious about competing with the regulars at the top of the division, then they need to work out how to get more money from matchday income.

Liverpool increased their capacity to 54,000 in 2016/17 by extending the main stand, but many of the additional tickets are sold to the prawn sandwich brigade, who are prepared to pay premium prices.

West Ham also have a large number (52,000) of season ticket holders. Add 3,000 away fans, and that only leaves 2,000 tickets available for irregular fans each match.

Like them or loath them, these fans/daytrippers/gloryseekers/football tourists (delete as necessary) generate a lot of money for a club, as they pay higher prices for tickets and are more likely to spend money on merchandise.

Some other clubs, with a more international fanbase, exploit this by restricting the number of season tickets to maximise their return from the football tourist brigade.

West Ham would have earned more money per fan had they progressed further in the Europa League, but Chelsea also did not have a European campaign, and they earned twice as much per fan.

Some credit (awaits flaming) could be given here to Sullivan/Gold for not taking fans to the cleaners in respect of prices.

Broadcasting

Broadcasting income was up by over a third to £119 million. This was due to the Premier League’s new deal with BT/Sky commencing.

The deal is for three years, so there will be no significant changes in this income source unless West Ham can (a) increase the number of appearances on television (they get £1 million for every additional appearance above ten), (b) Qualify for European competitions, or (c) Achieve more success on the pitch and move higher up the table (each position is worth £2 million more than the one below, so finishing 7th instead of 11th is worth £8 million to a club).

Whilst relegation is a nagging doubt rather than a huge concern at present this season, clubs in the Championship with parachute payments initially earn about £41 million from this source, and those without parachute payments about £7 million.

West Ham presently earn about two-thirds of their income from TV.

Winning the Europa Cup was worth £40 million in TV money last season to Manchester United, West Ham picked up £400,000.

Commercial

West Ham’s commercial income rose by a quarter to £35 million. This is impressive, but also reflects the market in which the club operates.

They don’t have the same international appeal as Manchester United, Liverpool or one or two other London clubs (clearly excluding small outfits such as Palace).

This means that they are competing with the likes of Everton, Newcastle, Southampton etc for the sponsors dollar.

We’ve heard anecdotal stories of sponsors playing clubs off against each other, so that if West Ham are looking for £10 million for a shirt deal, the sponsor will say “Newcastle will do it for £6 million, so drop your asking price or we go elsewhere”.

From the point of view of a generic overseas bookmaker, they don’t particularly care whether their logo is on the front of a Burnley, West Brom or Palace shirt, so long as it gets regular exposure on TV.

It looks as if West Ham have leveraged on the move to the new ground to increase commercial income, and there are potential future gains here too as old deals the.

This issue has implications for financial fair play too, as clubs are limited a £7 million increase in wages each year, plus any money generated by matchday, commercial income and gains on player sales.

The new stadium does give West Ham some scope to increase this income source, but the relationship with the landlord does restrict some of these opportunities.

They should therefore be at the top of their peer group of non ‘Big Six’ clubs (and Spurs are not really part of that elite to be honest), which will give them some additional buying power in the player market.

Costs

The main costs for a club are player wages and player amortisation (transfer fee costs spread over the life of the contract).

So when Andre Ayew signed for West Ham in 2016 for £20 million on a four year contract, this works out as an amortisation cost of £5 million (£20m/4 years) a year.

West Ham’s wage bill rose by 12% to £95 million in 2017. It’s a significant increase and puts the club ahead of some of its rivals, but is still behind Everton (£105m), Leicester (£112m) and some others that the club probably considers to be in the peer group.

The amortisation charge increased too, and if the two elements of player costs are added together then West Ham have doubled their player running costs over the last five years from £70 million to £140 million.

There’s a huge gap between this group of clubs and those that have dominated English football in recent years, and it’s difficult to see, especially with the new wage control rules of Financial Fair Play (FFP) how this can be bridged, unless the club qualifies for Europe, and for that you need better players, who want higher wages. This vicious circle prevents anyone breaking through the glass ceiling.

Although player wages are not disclosed, companies must show the pay of the highest paid director. In the case of West Ham this was £868,000, slightly lower than the previous year, but enough to allow the recipient to have the occasional pie and mash.

Whilst the name of the highest paid director is not shown, we suspect she has the initials KB.

One new cost for West Ham this season is the rent of the London Stadium. For reasons best known to themselves the accountants call rent ‘operating leases,’ and this rose by about £2 million in the year, which is in line with the figures quoted in the media.

As well as the running costs of the club, there are interest costs in respect of borrowings made by the club.

Fans might have thought that the club would have been able to repay all debt following the sale of the Boleyn, and therefore not pay any interest, but they would be wrong.

The club’s interest cost worked out at £97,000 a week in 2016/17. Whilst this is a lower figure than the previous season, half of it went to shareholders, in the form of loans from Gold and Sullivan.

This does mean that they strictly are correct in claiming never to have taken a penny as a wage from the club, trousering £50-60,000 a week in interest should prevent them from needing to sell The Big Issue just yet.

Gold and Sullivan have charged the club £14,875,000 in interest on loans since 2011/12.

Profit

Profit is an abstract concept, in theory it should simply be income less costs. In practice there are a range of profits quoted, depending on which costs are included.

West Ham in their press release stated they made a record profit of £43 million for 2016/17, which is the profit after tax figure. This is however after considering gains on player disposals, including that of Dmitri Payet, which generated profits of £28.4 million.

In addition, the club showed a profit on the sale of the Boleyn Ground of £8.6 million, and here we enter some choppy financial waters, which will be discussed in depth further in this epistle.

Whilst we expect to see clubs making a profit on player sales each year due to the way player signings are treated in the accounts, this figure is volatile as it depends on individual player disposals.

Excluding player disposals, West Ham’s EBIT profit (which is profit excluding one-off transactions such as the Boleyn transaction and player sales, before interest and tax) was £11.4 million, much lower than the quoted figure, but still an improvement on the previous year’s EBIT loss of £3 million.

The move to the new stadium may have helped here a little, but the main driver has been the extra £33 million of TV money.

Adding back the non-cash expenses in the form of depreciation and amortisation gives an EBITDA profit of £58 million, which is 77% higher that the previous year’s £33m. It is this profit figure that many analysts use when valuing businesses, and here West Ham have done reasonably well.

Player activity

West Ham spent a record £80 million on players in 2016/17, including Ayew, Snodgrass and Lanzini. Whilst this exceeds the club’s previous transfer activity, there is still a gap between the club and those they seek to compete with.

If you take away player sales from the purchases, then West Ham’s net spend was £40 million, roughly in line with the previous season.

Hidden in the footnotes to the accounts are a couple of interesting figures (interesting only to those who are still reading this tedious summary we suspect). The first is contingent liabilities.

This is the sum the club must pay to players and former clubs if certain achievements (appearances, trophies, international caps etc.) are met. This was £2.3 million and compares to £111 million for Manchester City and £45 million for United at the end of June 2017.

This suggests that West Ham have a different approach to the two Manchester clubs when signing players, aiming for a set fee with little based on future performance.

Borrowings

Many owners lend money to their clubs, if you look at the likes of Middlebrough, Newcastle (with the hated Mike Ashley), Brighton, Huddersfield, Stoke and so on, they all have owner lenders.

What these clubs also have in common is that the owners don’t charge interest on these loans.

Messrs Gold and Sullivan have lent the club £45 million, but have charged interest at 6% interest. The club then paid the owners £10 million in partial payment of the interest that had clocked up in August 2017.

This is perfectly legal, if somewhat at odds with the philanthropic approach taken by many other club owners.

The sale of the Boleyn Ground

It’s very confusing working out exactly what has happened in terms of the financial treatment of the club’s old stadium. If we’ve not bored the pants off your already, stop reading now, as it’s about to get even more tedious.

The club booked a profit of £8.6 million on the sale, but the history of the ground in the accounts is best described as erratic.

In 2012 the Boleyn was measured at a fair market value of £71.2 million. Admittedly this was for the stadium as well as the land surrounding it.

The following year the club decided to change the way it measured the Boleyn in the accounts, on the grounds that it was moving to the London Stadium.

This meant that the value of the stadium fell by about £40 million.

By the time the club had vacated the Boleyn in June 2016 the accounting value was about £30 million. However, this bears no resemblance to a market value. If the club booked a profit of just under £9 million then the sale price appears to be about £39-40 million.

According to the club, it sold the Boleyn to a property development company called Galliards, and inferred that they had turned down higher offers, but that Galliards would preserve some of the history of the club.

However, there appears to be a third party involved called Boleyn Phoenix Limited.

Boleyn Phoenix Limited was incorporated in January 2014 and is listed as a property development company. It has two shareholders, Galliard Holdings Limited and Mount Pleasant Developments Limited.

Boleyn Phonex was mentioned by Newham Council in relation to the redevelopment of the Boleyn Ground. The comments were not very positive.

Boleyn Phoenix Ltd had no sales in the first few years of trading, but in the year ended 31 March 2017 sprung into life and showed a profit of over £16.7 million.

Having made a huge profit, presumably on a deal for a property costing about £40 million and selling it for nearly £60 million. Boleyn Phoenix rewarded its shareholders by paying them a dividend of nearly £16 million.

Could this property have been the Boleyn Ground itself? It could be a coincidence.

Therefore Galliard Holdings would have received a dividend of nearly £8 million, as would Mount Pleasant Developments Limited.

Mount Pleasant Developments Limited have one shareholder, Vince Goldstein.

Now clearly there could be many Vincent Goldstein’s around, but a quick bit of Googling brings one to the fore in terms of property development.

This particular gentleman (who may or may not be the shareholder in Mount Pleasant Developments) is connected to the Rock Group and is the cousin of the former Vice-Chairman of Spurs, Paul Kemsley, who some may know from ITVBe’s magnificent The Real Housewives of Beverley Hills, where his wife, Dorit Kemsley, is one of the stars.

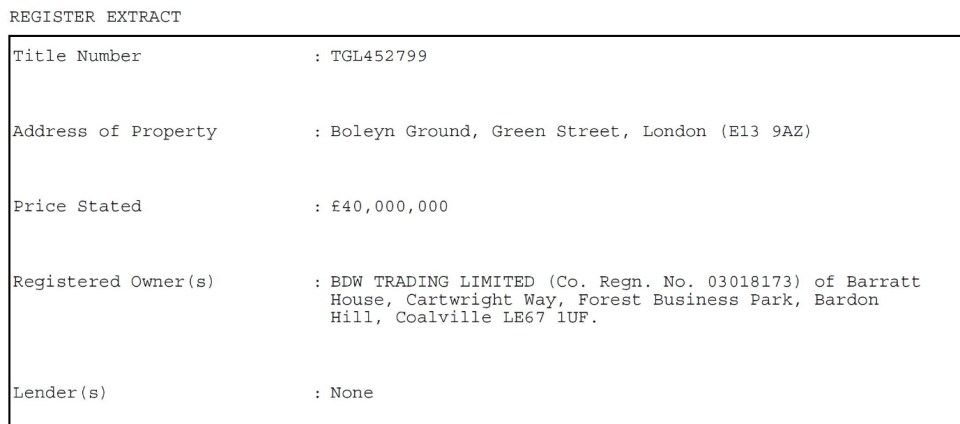

According to West Ham the Boleyn was sold to the Galliard Group, which could perhaps have been Boleyn Phoenix. The Boleyn Ground was then rapidly sold to Barratt Homes.

The Land Registry says that the price paid for the Boleyn Ground by Barratt was £40 million, which begs the question, how did Boleyn Phoenix make a profit of nearly £20 million?

There’s no evidence of any wrongdoing, it’s just a bit…odd.

Summary

West Ham’s accounts provide as many questions as answers. There’s a lot of bad blood at present between the club owners and some elements of the fan base. More transparency in relation to the club and its transactions would possibly help resolve some of the differences.

The hope that the move to the London Stadium doesn’t seem to have pushed the club onto the next level of success in the Premier League, and this is why some fans are wondering was it worth losing their spiritual and cultural home that was the Boleyn Ground.

As Alice said to the rabbit ‘Curiouser and curiouser’.

Data Set

3 Comments

Andrew Quinn

“Gold and Sullivan have charged the club £14,875,000 in interest on loans since 2011/12.“ is this correct?

The Baron

Yes, they have charged interest on the £45 million loan since acquisition of the club and took out £10 million as a part payment of that interest in August 2017.

Matthew Porter

Yoiks! said Shaggy. We’re for it, Scoob.