Burnley: Your name’s not down, you’re not coming in

As The Notsensibles are one of our favourite bands, it’s time to take a look at the financies of Burnley as the club celebrated their most successful season to date in the Premier League in 2016/17 by finishing six points above the drop and have since used this as a springboard to be presently challenging for a European place.

As The Notsensibles are one of our favourite bands, it’s time to take a look at the financies of Burnley as the club celebrated their most successful season to date in the Premier League in 2016/17 by finishing six points above the drop and have since used this as a springboard to be presently challenging for a European place.

The club, along with manager Sean Dyche and the players, don’t get the credit they deserve for winning matches and playing decent football, with too many critics lazily linking Dyche’s nightclub bouncer dress code, Dalek like voice to a club with the ethos of a slightly upmarket Wimbledon of the Crazy Gang era.

There are three companies involved in the running of Burnley

(a) The Burnley Football and Athletic Company, formed in 1897, runs the club’s day to day operations.

(b) Longside Properties Limited, which appears to own Turf Moor and rent it to the football club.

(c) Burnley FC Holdings Limited, which owns 100% of the shares of both the above companies, and which forms the basis for this analysis.

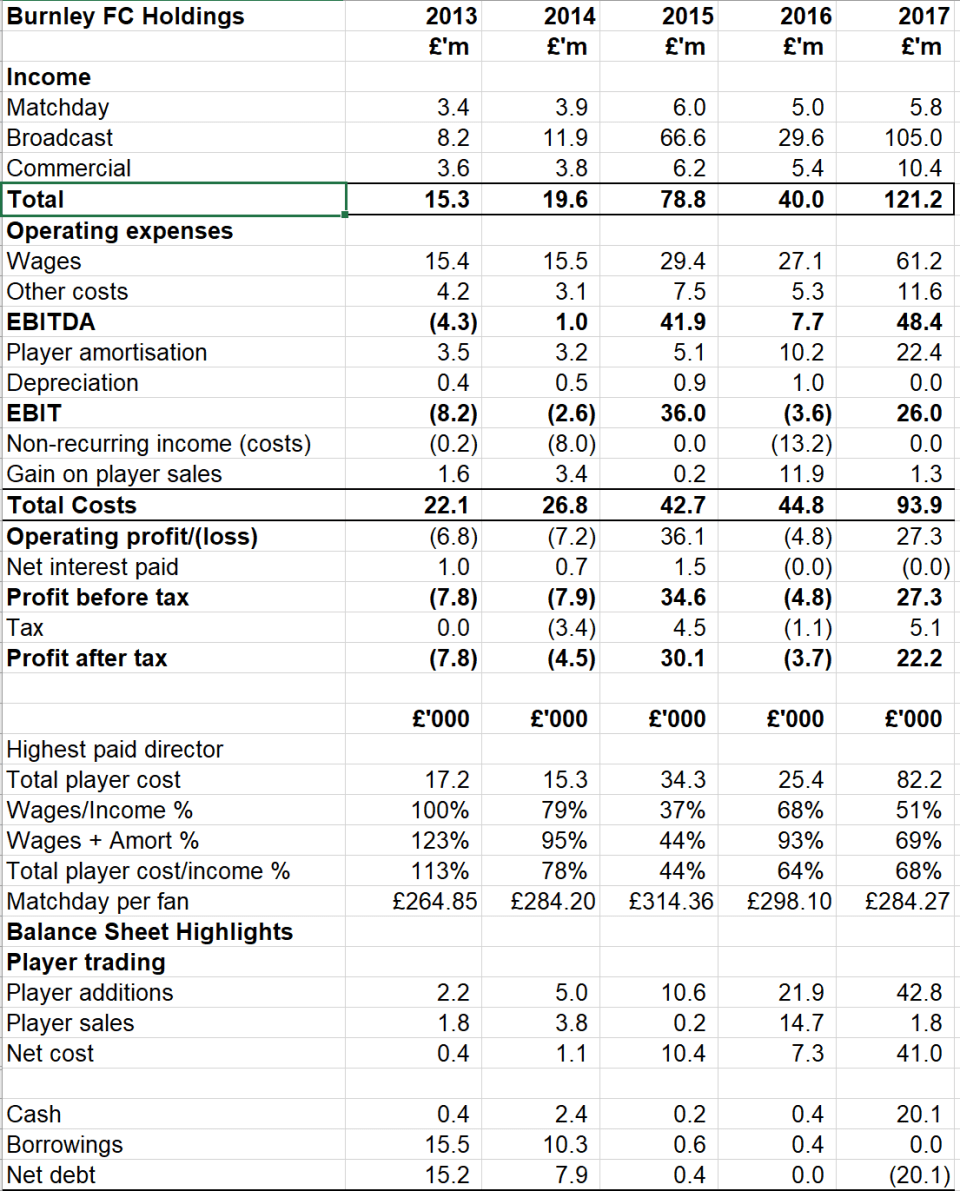

Executive summary of key figures (Burnley FC Holdings Limited)

Income £121.2 million (up 203%)

Broadcasting income £105 million (up 254%)

Wages £61.2 million (up 126%)

Profit before player sales £26.0 million (Loss of £3.6 million in 2016)

Player purchases £42.8 million (£21.9 million in 2016)

Player sales £1.8 million

Borrowings: None

Income

Burnley have bounced between the top two divisions in recent years, with three promotions and two relegations since 2009, and this is reflected in their volatile income levels.

Burnley have been beneficiaries of either Premier League membership or parachute payments since 2010, and the sharp spikes in income in 2010, 2015 and 2017 represent the years in which they have been in the top flight.

Although it tripled in 2016/17, Burnley’s overall income was the second lowest of Premier League teams last season. Talk to a Lancastrian, and they will tell you it’s not about how much money you earn, but spending it wisely that matters, and The Clarets have wasted little and added strength to their team after surviving last season.

Eighteen clubs who were in the Premier League last season have reported their results to date. Only car crash Sunderland, probably too busy setting the club coach’s sat nav to Accrington, and small London outfit Crystal Palace have failed to do so.

All Premier League clubs are reporting higher income for 2016/17 than in the previous season. The average income of the 18 clubs that have reported to date is £239 million, up 31% from £182 million the previous season. The average in the Championship is just £28.6 million.

Burnley therefore earned half of the average income in the division, such is the way that money is skewed towards the ‘Big Six’ in the Premier League of Manchester United and City, Liverpool, Arsenal and Spurs (even though the latter haven’t won the title for nearly 60 years).

The main reason for the increase in overall income in the Premier League for 2016/17 was the new Sky/BT domestic TV deal, worth £5.1 billion over three seasons.

The Premier League divide money into five pots. Three of the pots cover the domestic TV deal, and they are split 50% evenly, 25% based on the number of TV appearances (every club is guaranteed a minimum of ten of these) and 25% based on final league position. Each place up the table is worth just under £2 million.

Overseas broadcasting income and centrally agreed commercial deals are split evenly between the twenty clubs. This arrangement is likely to come under fire in the summer as the ‘Bix Six’ want to grab a bigger slice of this pie for themselves. Their argument is that overseas TV fans would rather watch one of their clubs than that of a team such as Burnley, and so they ‘deserve’ more money.

Whilst this argument is true in terms of the number of viewers, it ignores the fact that the ‘Other 14’ can compete against most clubs in Europe apart from the elite for players (all 20 EPL clubs are in the top 35 richest in Europe) and thus can put up a decent performance against the Big Six.

This partly explains why Burnley won at Chelsea, Huddersfield beat Manchester United, Swansea beat Liverpool and many clubs have turned over Arsenal.

Like all clubs Burnley earn their income from three sources, matchday, broadcasting and commercial/sponsorship.

Matchday income increased by 17% to £5.8 million. This appears to be due to higher attendances (a 23% increase to 20,558) rather than increased ticket prices.

Matchday income was enough to pay Alexei Sanchez’s wages for three months and represents only represents 5% of the club’s total income.

Burnley had the second lowest matchday income total in the division, but still managed to be survive and thene thrive. This shows that size doesn’t necessarily matter, it’s what you do with it that counts (something I’ve been trying to persuade my slightly disappointed wife of for years).

Ticket prices seem to have fallen since Burnley’s last season in the Premier League, with matchday income averaging £284.27, about 10% lower than in 2015. This works out at £14.96 per match, which may surprise some Clarets, but remember this is the average of adults, seniors and kids, and is also net of VAT.

Broadcast income is the one most sensitive the division in which a club plays. Even though Burnley had the benefit of parachute payments in 2015/16, broadcast income still rocketed from £30 million to £105 million.

The present domestic deal lasts until 2018/19, so don’t expect to see Burnley increase their broadcast income until the following season, unless they significantly improve their final league position (likely, and finishing 7th will bring in an extra £18 million compared to finishing 16th) or qualifying for Europe, which is presently possible. Manchester United made £40 million from winning the Europa League in 2017.

Commercial income nearly doubled to £10.4 million, mainly due to the club signing a new shirt sponsorship deal with Dafabet worth £2.5 million a year.

Cost

The main costs at a football club are player related, wages and transfer fee amortisation.

Burnley’s wage expenditure last season is noticeably different to when they were promoted in 2013/14. To a certain extent Burnley budgeted for relegation in 2014/15, and duly went down. They were then in a very strong position to pay relatively high wages in the Championship in 2015/16, and were able to retain key squad members and recruit the likes of Joey Barton to help the club go up as champions.

This time Burnley substantially increased the wage bill, and it was enough to ensure the club stayed up.

Even though the wage bill more than doubled, Burnley had the lowest wage bill in the Premier League in 2016/17.

Burnley players are however unlikely to be seen selling copies of The Big Issue to make ends meet, even as the lowest payers in the division, wages average £29,422 a week.

The riches of the Premier League TV deal meant that Burnley only paid out £51 in wages for every £100 of income. The club’s strategy for 2015 is also highlighted here when it was only £37 in wages. In the Championship over half the clubs pay out more in wages than they generate in income, leaving club owners to pay the rest of the bills.

Amortisation (skip this bit unless you want a quick and dirty accounting lecture) is how clubs deal with transfer fees in the profit and loss account. When a player signs for a club the transfer fee is spread over the life of the contract. Therefore, when Burnley signed Robbie Brady for £13 million from Norwich on a 3½ year deal, the amortisation charge works out as £3.7 million a year (£13/3.5). The amortisation fee in the profit and loss account includes all players who have been signed for a fee (assuming they are still in their initial contract).

Burnley’s amortisation total of £22 million is double that of the previous year, but also tellingly four times that of the club’s last Premier League season. This again suggests the club was using their 2014/15 season in that division as an ‘air shot’, effectively budgeting for relegation and anything other than that was a bonus.

Burnley’s total amortisation in 2016/17 but still one of the lowest in the division. This is partially due to the club’s recruitment of hardworking players such as Ashley Barnes for £300,000, who according to the bellend element of his former club Brighton, was only Sunday league standard.

Profits and losses

Profits are income less costs. Burnley made a lot of profit in 2016/17. This was lower than their previous season in the Premier League due to, as we have already seen, the Clarets in 2014/15 paying relatively low wages and spending little in the transfer market.

Operating profits are income less the running costs of the club (wages, maintenance, insurance, amortisation etc. and they are before deducting interest and promotion costs and player sale profits. In 2016/17 this worked out as £26 million, or £500,000 a week. The previous season the club lost £3.6 million, and this was before paying out over £13 million in promotion bonuses.

Under Financial Fair Play (FFP) rules, Premier League clubs can make a maximum FFP loss of £105 million over three years. Burnley clearly have little to fear in this regard.

Player trading

The accountants treat player trading in a weird way in the financials. We’ve already shown that when a player is signed, his transfer fee is spread over the life of the contract. When the player is sold, the profit is shown immediately, and it based on the player’s accounting value, not the original transfer fee.

This creates erratic and volatile figures in the profit and loss account.

If we instead focus on the actual purchase and sales, the following arises

The above table shows that over the last five years Burnley have bought players for £82.5 million and generated sales of £22.3 million, a net cost of £60.2 million over the period.

Burnley’s spending in 2016/17 was a record sum for the club, but pales into insignificance in relation to the big Manchester and London clubs.

Debts to and from the club

Burnley didn’t sell many players before the 2017/18 window, and so were only owed £1.7 million by other clubs for players at 30 June 2017.

The club did owe other clubs nearly £16 million for player transfers, but this is chicken feed compared to the likes of Manchester United who owe over £180 million.

Perhaps more importantly the club is debt free, with no borrowings from either banks or the club owners.

Summary

Burnley have shown that a club can match some of the bigger spenders in the division in terms of wages and player transfers, and still stay in the Premier League.

The way they have pushed on this season, through hard work and superb defending, gives hope to others within the ‘Other 14’. They are guaranteed another season in the top division and about £125 million in TV income this season, which Sean Dyche can use in the summer transfer market.

Unfashionable yes, underrated certainly, but they are in the top half of the division on merit, and with a potential European campaign to look forward to next season.

Based on the financials for 2016/17, the club is worth a total of about £350 million using the Markham Multivariate Model. This figure looks a little top heavy, but even so it shows the attraction of the Premier League to investors who might want to risk their money in a club that looks after the pennies and can still win plenty of matches.

Data Set