Burnley 2017/18: I Thought You Were Dead

Seventh position in the Premier League and qualifying for the Europa League was an achievement for Burnley in 2017/18 and the club’s financial results were almost as impressive.

Earnings, wages and player trading profits all hit record levels yet some fans seem bored by life in the Premier League.

Income

All clubs split income into three categories to comply with EPL recommendations, matchday, broadcasting and commercial.

Nowadays most ‘Other 14’ clubs earn a small fraction of their total income from matchday sales and Burnley is no exception as frozen ticket prices and slightly less domestic cup progress meant that this fell by £200k compared to the previous year.

Due to having a relatively small ground capacity and few prawn sandwich eating fans there’s little scope for this income source to grow in the future so Burnley, with a population of 80,000, have to expect to be in the bottom six of matchday earners in this division.

Year on year Burnley’s matchday income fell by 4% last season but has been relatively static during the Premier League seasons.

Contributing just 4% of total revenues means that whilst the club doesn’t take fans for granted its focus will be ensuring Premier League membership and taking a pragmatic approach under Sean Dyche to earning points.

Having to compete with glamourous clubs within a fifty mile radius means that Burnley has to price tickets keenly and has the second lowest matchday income per fan in the Premier League.

Earnings from broadcasting increased by £16.5 million mainly due to higher prize money from the Premier League.

How the Premier League distributes broadcast money from both domestic and international TV deals is a thorny subject and the cause of much argument between club owners.

A half of the broadcast income domestically and all international deals are split evenly between all twenty EPL clubs, whereas a quarter is based on the number of live TV appearances and a further quarter is prize money linked to the final league position.

Seventh position meant that Burnley earned £24.7 million in prize money, which starts off at £1.9million for the team finishing bottom and increases by the same amount for each additional place in the table.

A million pounds is paid to clubs for each live appearance on BT/Sky and clubs are paid for a minimum of ten matches although for Burnley were only chosen for seven despite their strong position in the table.

Premier League broadcast payments are the lifeblood for a club such as Burnley, so it is no surprise to see that it was responsible for over 87% of total income.

Expect broadcast income to be slightly lower this season (2018/19) as Europa League income from the qualifying rounds is unlikely to offset the decrease in Premier League prize money.

Trying to sign up new sponsors and commercial partners is tricky in the present economic environment.

Having a potential global audience watching Burnley works fine when the club is playing Manchester United or Liverpool but doesn’t attract viewers when it’s a small club such as Crystal Palace.

A lot of clubs in the Premier League have gambling companies as their shirt sponsors and Burnley are no exception, with Laba360 replacing Dafabet as the Clarets signed a record deal that helped boost commercial income by 14% in 2017/18.

Manchester United are in a league of their own when it comes to commercial income (neighbours City are fortunate to have owners who have influence over some sponsor deals) but Burnley are in a fairly large group of 8-9 clubs whose income is broadly similar from this source.

Selling the charms of Turf Moor isn’t easy for the commercial team as the location isn’t in London or another large metropolis and sponsors will often try to barter down a price by threatening to take their money to another club of similar stature in the PL.

Total income for the Clarets was up nearly 15% and very dependent upon continued Premier League status which appears to have been achieved until at least 2019/20.

Even monied clubs such as Stoke, Swansea, Hull and Sunderland have been relegated in the last two seasons and struggled to make much of an impact in the Championship, which highlights just how important it is for Burnley to avoid getting into a relegation fight as there are no guarantees of coming straight back up.

Relative to its peer group Burnley’s total income is towards the top end of those clubs who would be expected to be in the bottom half of the Premier League at the start of the season.

Costs

Costs for a PL football club are focussed on player related expenses, namely amortisation and wages.

Amortisation is the cost of all the transfer fees paid by the club spread over the contract life, so when Burnley signed Chris Wood for £15 million from Leeds on a four-year deal this works out as an amortisation charge of £3.75 million a year (£15m/4).

Life in the Premier League is expensive and Burnley’s amortisation charge increased by over £5 million as Wood, Cork, Wells, Walters etc. came at a total cost of £43 million, offset by not having to amortise Keane and Gray when they departed at the start of 17/18.

Looking at amortisation it can be an indicator of potential relegation as West Brom and Stoke, both established PL clubs, were at the bottom of the table, with Brighton and Huddersfield unsurprisingly below them as they’d both just been promoted to the top flight for the first time.

Everyone has an opinion on football player wages but Burnley seem to have a fairly tight policy where all players are paid within a narrow range and this has an impact upon the nature of who they recruit and let go.

Driven by prize money bonuses for finishing 7th, Burnley’s total wage bill increased by 33% to over £81 million, over five times the level when the club was in the Championship and receiving parachute payments.

Burnley’s wage bill however was still the third lowest in the division despite the large increase in the year and based on our (somewhat crude) calculations work out at about £39,000 a week.

In letting Michael Keane go to Everton for three times that wage level Burnley seem to have a strategy that is appealing to players who want to further their career and see the club as a stepping stone to a ‘bigger’ club should they perform well at Turf Moor.

Getting the balance right between player costs (amortisation and wages) and sporting success on the pitch is challenging but Burnley have done supremely well in 2017/18 in paying out £79 in player costs for every £100 earned, leaving plenty to pay the other day to day overheads of running the club.

Profit

Defining profit is always tricky as there are many variants, but most simply put profit is income less costs although that contains lots of layers and distractions.

A lot of clubs cherry pick one of the many different profit figures available and Burnley have partially done this on their website by announcing a record net profit of £36.6 million.

Various alternative figures could have been used though and we will look at these in some detail.

Everyday profits arising from income less all the running costs of the club except loan interest are often referred to as ‘operating profits’. This a ‘dirty’ measure in that it includes one-off non-recurring costs such as redundancy when a manager is sacked or volatile gains arising from player sales that are best eliminated when trying to work out long term sustainable profitability.

Burnley’s operating profit was even more impressive than the figure quoted in the club website at a £45 million, higher than that of Manchester United.

A big driver of Burnley’s profits for 17/18 was profits from player sales. The sales of Keane and Gray generated a profit of over £30 million, compared to just over £1 million the previous season.

Stripping out player sale profits and other non-recurring items (redundancies, legal cases, debt write offs etc.) gives a more constant profit measure called EBIT (Earnings Before Interest and Tax).

Burnley’s EBIT profits are still impressive but lower than the two previous seasons in the Premier League when the club’s wage bill was far lower.

The Premier League EBIT table shows just how dependent clubs are on player sales in making the books balance. Liverpool, for example, saw their profits fall from the world record £131 million quoted in the press to just £7m once the Coutinho profit (which won’t arise every year) was removed.

If non-cash costs such as amortisation and depreciation (depreciation is the same as amortisation except this is how a club expenses other long-term asset such as office equipment and properties over time) then another profit figure called EBITDA (Earnings Before Income Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation) is created. This is liked by professional analysts as it is the nearest thing to a cash profit figure.

Burnley’s EBITDA profit was £44 million which shows that the club is generating cash from its day to day activities which can then be reinvested into the playing budget when Sean Dyche is looking to recruit players.

Once trading costs have been paid, many clubs also have to pay interest on their borrowings, which in Burnley’s case was nothing, and tax on profits, which came to £8.5 million. Adusting for these two figures gives pre and post-tax profits, which takes us to the record profit figure quoted by the club itself of £36.6 million.

Player Trading

Burnley spent £43.5 million on new players in the year to 30 June 2018 as the club strengthened its squad, note that the sum committed was broadly similar to the EBITDA profit from the previous season.

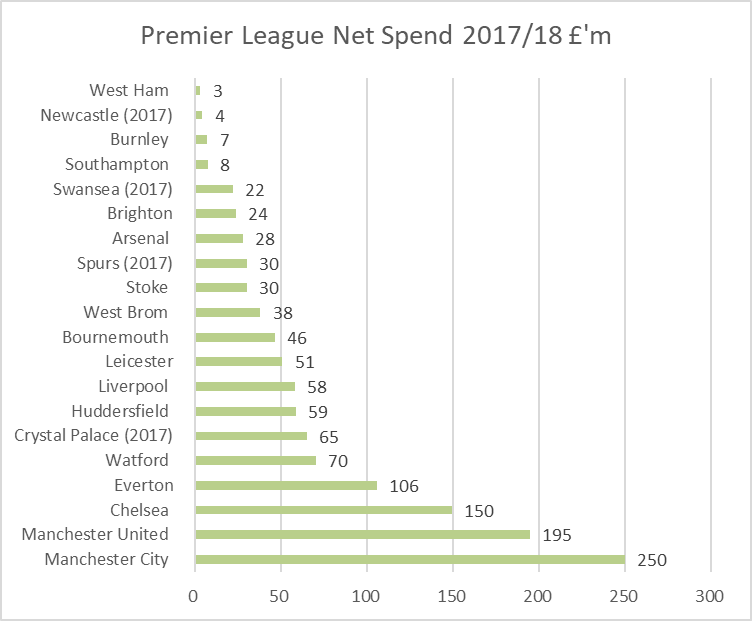

The large spend on players is why the amortisation charge in the profit and loss account is so high. Fans often point out that clubs also sell players and that net spend is a better measure of a club’s investment in talent.

Burnley had a net spend of only £7 million in 2017/18 so to achieve their final legal position on such as modest outlay is a testament to the management, coaching team and commitment of the players.

Funding

Clubs can obtain funding in three ways, bank lending, owner loans (which may be interest free) or issuing shares to investors. Historically Burnley have run a very tight ship and used the money generated through on the field, especially broadcast income and parachute payments to fund player purchases and this continued in 2017/18. The club owners have not had to dip their hands in their pockets for many years.

Key Financial Highlights for year ended 30 June 2018

Turnover £139 million (up 15%)

Wages £82 million (up 33%)

Pre-player sale profits £14.4 million (down 45%)

Player sale profits £30.7 million (up from £1.3 million)

Player signings £44 million (up from £43 million)

Summary

Burnley achieved a miracle in 2017/18 that went relatively unheralded. Unloved by broadcasters, too workmanlike for the pundits to get excited about, they went about their business and the players were drilled repeatedly to get results.

The Europa League at the start of 2018/19 was a step too far and it was a blessing in disguise they were eliminated so early as it allowed Sean Dyche to get back to what he does best, training players hard for five days for the next fixture.

Barring a miracle they will be in the Premier League in 2019/20 where once again they will fly under the radar, accumulating points but getting little credit for doing this without handouts from owners.

One Comment

Roy Holtom

Very fair summary of our club, in a year that was remarkable in many respects.

Worth pointing out that the last two years’ Wages totals include significant bonuses, which prior to 2017 were shown separately in the accounts. Therefore, for strict comparison purposes, the 2016 figure of £27.1m needs increasing by the bonus that year of £12.1m. Thus a total figure of over £39m.