Brighton 2019/20: Reel around the Fountain

Introduction

Getting to the Premier League is an expensive business as many clubs in the Championship have found out, with operating losses in that division exceeding £600 million pre-Covid.

Remaining in the Premier League can also be costly, as Brighton have proven in announcing their 2019/20 financial results.

Income

All clubs divide their revenue into three categories, matchday, broadcast and commercial.

Having matches taking place behind closed doors at the end of the season meant that Brighton’s matchday revenue fell by over a quarter to £13.5 million.

Albion make about £1 million per home match, more so against the big teams, and so this meant that they are likely to have a financial hit of about £18 million in 2020/21, assuming that there are no matches played before a paying audience for the remainder of the season.

Matchday income historically made up about 13% of Brighton’s total revenue in the Premier League, but it was over half of the total when the club was in the Championship.

Premier League clubs can only increase matchday income by increasing prices, capacity or the number of events that take place at the stadium, until the fallout from the pandemic ceases then clubs collectively are set to lose about £700m from this source.

Overall attendances averaged 30,359 in 2019/20, down 0.2% pre-lockdown, the club has the intention to increase the capacity slightly at the Amex but there is a natural ceiling of about 32,000 without a huge infrastructure cost.

There is limited opportunity for Brighton to host other events at the Amex, so if the club wants to increase matchday income it will have to find ways of increasing the average spend from corporate and hospitality customers.

The other clubs who have published their 2020 accounts (in red above) have all reported decreases of about 20% in matchday revenues.

Earnings from sponsorship historically have been mainly from American Express and Nike for Brighton, but in addition the club generated over £10m from a property development called New Monks Farm close to their training facilities in Lancing, as well as increased loan income for the season.

Revenue from commercial activities is very much concentrated in the hands of the ‘Big Six’ clubs, who between them earn 77% of the total.

Half the clubs in the Premier League have gambling companies as sponsors who historically have paid more than other industries for the non ‘Big Six’ clubs but Brighton seem to have bucked the trend by aiming for a long term relationship with American Express which seems to have paid off.

Half the clubs in the Premier League have gambling companies as sponsors who historically have paid more than other industries for the non ‘Big Six’ clubs but Brighton seem to have bucked the trend by aiming for a long term relationship with American Express which seems to have paid off.

Albion, like all Premier League clubs, benefit from the Premier League’s record breaking broadcasting deals, but had a 21% fall from this source in 2019/20.

Six matches in 2019/20 took place after the club’s 30 June year end and so the full season’s broadcast income was reduced to 32/38 of the total broadcast income for the season, which means in 2020/21 it should be 44/38 of the usual amount.

A complex formula is used to divide Premier League broadcast money between clubs, based on fixed sums split evenly, appearances on television and the final league position, plus some clubs earn extra through qualifying for UEFA competitions.

Finishing in fifteenth position in the Premier League meant that Brighton earned just under £4m more from the positional pot than the previous season, but this was offset by an estimated £330m rebate to broadcasters plus not finishing all matches by 30 June 2020.

Rebates to broadcasters are likely to be spread over three years, probably in the form of Sky, BT Sport and others paying slightly less than their originally agreed fees, how this will be split between the clubs is still uncertain.

Every other club who had reported their accounts to date for 2019/20 has shown substantially lower broadcast revenues, so whilst Brighton are bottom of the table at present, this is likely to change in due course.

Nestling towards the bottom of the total revenue table is to be expected for Brighton, they were 14th and 15th in the previous two seasons in the Premier League following promotion.

Costs

Club costs mainly relate to players, in the form of wages and transfers.

Having been promoted in 2017 Brighton’s costs in their first season in the Premier League increased more slowly than income, allowing the club to make a profit, but this initial benefit reversed in the second season and losses accelerated further in 2019/20.

Life as a footballer generates much comment, but statistical analysis suggests that you tend to get what you pay for in football, overall wages stabilised for Brighton in 2019/20, some players went out on loan, others left, and were replaced by others on broadly similar salaries.

Locadia, Knockaert and Andone went out of loan, freeing up wages to bring in Maupay, Lamptey and Webster, allowing the overall wage bill to be static.

Another reason why wages have not increased is that bonuses for the last six matches of the season are not included as these matches took place after 30 June.

Moving from League One football at ‘The’ Withdean to the Premier League in the Amex stadium has seen wages rise by 1,353% over the last decae, but they are still modest by comparision with the rest of the division, with average wages of £48,000 a week.

A percentage of revenue basis shows Brighton’s wages in 2019/20 were the fourth lowest relative to income in the last decade.

Chief executive Paul Barber, on the list of many a head hunter if media reports are correct, saw his pay rise to over £2million, including a loyalty bonus, which is less than the average player salary of £2.49 million.

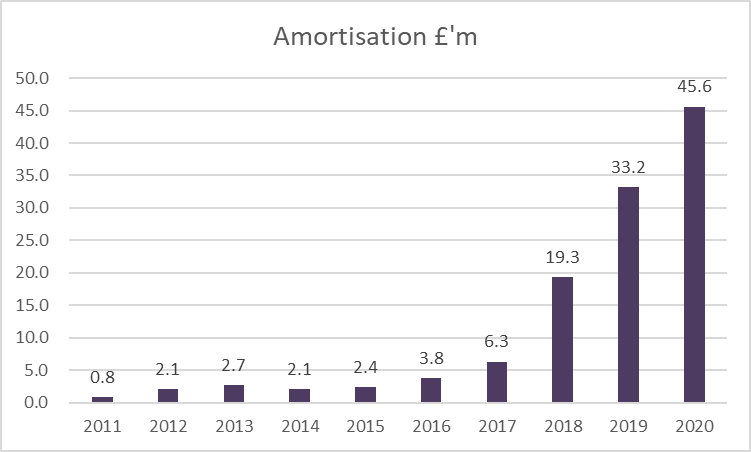

Amortisation is the other main player related cost and this is total transfer fees spread over contract life, so the signing of Adam Webster for £20 million on a four year deal works out as an annual amortisation cost of £5 million (unless you’re Derby County, in which case it is mysteriously lower).

Luckily for Brighton some players, such as Solly March and Lewis Dunk have come through the ranks at the club and so there is no amortisation cost, which has still increased on the back of the signings of Webster, Maupay and Lamptey.

Losses

Losses (and profits) are income less costs and Brighton’s operating (day to day) loss of £64 million may surprise some but the figure reflects the impact of Covid-19, which the club estimated contributed £25 million for the year.

Everton, Southampton and Spurs have also published significant operating losses for 2019/20 and this trend is likely to be repeated for the vast majority of established clubs in the division.

Due to player sales profits, these losses can be reduced, but Brighton made no return from this activity in 2020, although the club now have a large number of players who could be sold for sizeable fees should there be interest from other clubs.

A club can therefore convert losses into profits from player sales (Crystal Palace did this in 2019 with the sale of Wan-Bissaka) but there are no guarantees of such profits, which tend to vary from season to season.

Player trading

Detailed breakdowns of player signings are never given in Premier League club accounts but Brighton spent over £55 million in 2019/20, taking their total spending to £191 million.

A Premier League club has to continually invest in players and Brighton’s total squad cost hit £200 million by 30 June 2020, which may increase slightly again in 2020/21

Making money from player sales is important for cash flow purposes, but Brighton have had a policy of keeping theirs since arriving in the Premier League.

Funding

Brighton have been dependent upon owner Tony Bloom for over a decade. He originally was providing money for signings (such as Glenn Murray from Rochdale in 2007 for £300k) behind the scenes but since becoming chairman has underwritten the cost of the stadium, training ground and operational losses to a total of £394 million.

This investment in split between interest free loans and shares, and 2018/19 was no exception as he lent the club a further £37 million to provide funds for further infrastructure and player spending.

Whilst no doubt Bloom wants the club to be self sufficient at some point, at present his benevolence has advanced the club from the wrong end of League One to a fourth season in the Premier League. More investment may be required if his stated aim of a regular top ten place in the Premier League is achieved.

In addition Brighton have taken advantage of government schemes to delay paying taxation, which has increased the tax creditor from £6m to £26m, and transfer creditor have risen from £12m to £37 million, suggesting that the signings of the Maupay, Webster and Co have been made on an instalment basis.

Summary

So, where does this leave Brighton? Since arriving in the Premier League four clubs (Fulham, Cardiff, Huddersfield, Norwich ) also promoted from the Championship in or since 2017 have been relegated.

Fans have been impressed with the style of football under new manager Graham Potter, but poor home form has caused grumbles on social media. Avoiding relegation in 2020/21 is important in a Covid-19 world where matchday income is uncertain for the foreseeable future.

Brighton are fortunate to have an owner in Tony Bloom who has a strategy for the club and as such is unlikely to indulge in some of the madcap short term schemes that have left many in the EFL looking very vulnerable.