Bolton Wanderers: What’s the frequency Kenneth?

Ken Anderson, Bolton Wanderers Swiss/Monaco resident rogue chairman until the club went into administration, has been in the firing line recently from fans, players, other clubs, unpaid creditors and the local media.

Even before Anderson was involved with the club Wanderers had been struggling financially, despite once heady days in the Premier League and a benevolent former owner.

Nat Lofthouse, the Lion of Vienna, is no doubt spinning in his grave as a series of damning stories have been publicised over the running of the one club he played for during his whole career.

A look at Bolton’s most finances over recent years shows highlights the club’s decline that has led to the present debacle as Burnden Leisure Limited, the parent company that owns both the football club and a nearby hotel, has posted the following figures in the year ended 30 June 2017.

Burnden Leisure Limited Key Figures

Income £14.7 million (down 52%)

Wages £13.8 million (down 38%)

Trading losses £13.5 million (up 67%)

Player signings £0.0 million

Player sales £6.3 million

Borrowings £22 million (down 19%)

Income

Nowadays most clubs divide their income into three main categories, Bolton are slightly different in they own a hotel via Burnden Leisure and so have four sources of revenue.

Day to day income is rare for a football club, which realistically is only open when a match is played.

Earning money from matches becomes more important as clubs drop down the divisions due to lower TV revenues and this impacted upon Wanderers in 2016/17 as they spent a season in League One.

Revenue from matches held up in 2016/17, partially due to average attendances, despite relegation, rising from 15,194 to 15,887, but is significantly lower than the final season in the Premier League in 2011/12.

Some clubs in League 1 don’t publish their profit figures, but from the ones that are available Bolton were towards the top of the matchday income table.

Overseas TV viewers don’t have a huge appetite for third division English football, and whilst there’s a bit more interest domestically there are few live matches shown either, which explains why broadcast income is so low in this division and has fallen 96% since Bolton were in the top flight.

Nevertheless, Bolton were in receipt of parachute payments for four seasons following relegation, but the ending of these, combined with a further drop into League One, was catastrophic for the club in 2016/17.

Hotel income fell by 16% in 2016/17, probably due to a combination of fewer away fans making overnight stays for weekends in Bolton as away followings tend to be lower, along with general economic trends in the hospitality market.

As the club was on live television far less often in 2016/17 and the nature of the opposing teams was less glamourous, it made it more difficult for the commercial department to sell sponsorship deals, and this was why commercial income more than halved.

Sponsors are often local companies and they are also less likely to be keen to have a large marketing and entertainment budget for events such as football given Brexit uncertainty.

Although a club such as Bolton doesn’t have the global appeal of the likes of Manchester United or Liverpool, it can still be seen when Championship games are broadcast internationally and so expect this to rise in 2017/18.

Some fans think that shirt sponsorship deals are worth a fortune to clubs, but in the Premier League these are sometimes worth no more than £1.5 million a season, in League One it is likely to be in the tens of thousands.

Merging all the income sources together results in Wanderers having the highest total in League 1, but if hotel income is excluded this fall to £8.3 million, which shows that it was a decent achievement for the club to be promoted that season.

At least by being back in the Championship Bolton will be earning more TV money, as the EFL deal and solidarity payments from the Premier League work out at about £7million a season compared to League One.

Costs

League One income is lower than that of the Championship, but costs don’t necessarily fall as swiftly.

Like all clubs, Bolton’s main expense is in relation to players, in the form of wages and transfer fees.

Wage costs fell by a third to £13.8 million and were about a quarter of the amount that Wanderers were paying when they were in the Premier League in 2011/12.

Included in the wage total is about £1.2 million relating to the hotel, which should be noted if comparing Bolton to other clubs in the division.

League One clubs (excluding those that use a legal loophole to avoid disclosing their costs) had an average wage bill of £6.1 million in 2016/17 and whilst Bolton’s costs were twice this it would have partially due to promotion bonuses, as well as some players being on Championship contracts that didn’t contain large relegation reduction clauses.

Love them or hate them, player wages are a regular topic for discussion amongst fans and based on a rough and ready formula we estimate that Bolton’s first team squad would have been averaging £335,000 a year.

You often hear fans saying that they ‘pay player’s wages’, but this isn’t the case in reality. The matchday income for Bolton for 2016/17 worked out at 25 pence for every pound of wages.

Transfer fees are dealt with in the accounts by something called amortisation. This takes the total transfer fees paid by the club and spreads it over the number of years of the contract signed by the player. So, when Nicolas Anelka signed for Bolton in 2006 for £8 million on a four-year contract it worked out as an annual amortisation cost of £2 million.

As the club’s finances have deteriorated in recent years it has had to reduce the sums paid for players and this impacted upon the amortisation total.

Bolton’s amortisation cost has fallen by 97% since being in the Premier League, which reflects the nature of loans and free transfers that are the most common methods of signing players in League One.

Bolton also paid £33,000 a week in 2016/17 in interest charges, partly due to an unusual arrangement with a company called Sports Shield BWFC Limited, controlled by Dean Holdsworth, which charged a Wonga-Tastic 24% interest per annum before going into liquidation.

It looks as if the interest due to Sports Shield will not be paid following a dispute with the club, so there should be a £1m reversal of interest charges in the 2017/18 accounts.

Further costs related to Ken Anderson, the club owner who was previously barred from being a company director in the UK for eight years.

As someone who used to work in the insolvency industry, you would have to irritate the authorities a huge amount just to get a telling off, so his behaviour in achieving an eight-year ban (which expired a few years ago) must have been spectacular in terms of poor governance and transparency. David Conn, The Guardian’s superb rottweiler like investigative journalist, uncovered some of Anderson’s past that does not paint him in a particularly good light.

Anderson was paid £525,000 for his services via Inner Circle Investments Limited, a company he set up in 2015 with an investment of £1 of shares.

By having such an arrangement, it allows him to legitimately say that he is not being paid a salary by Wanderers.

Inner Circle Investments Ltd appears to be little more than an investments vehicle, as the only asset it owns is a 95% share in Burnden Leisure.

Inner Circle Investments Ltd appears to be little more than an investments vehicle, as the only asset it owns is a 95% share in Burnden Leisure.

In addition, £125,000 was paid to another member of the Anderson family, which appears to Ken’s son Lee Anderson, via something called the Athos Group. A trawl of Company’s House reveals that Athos Group is a services company that seems to have no executive called Lee Anderson. It would therefore appear that Lee was paid for consultancy or other work, such as modelling BWFC leisurewear. Whether a future career on the catwalk for Lee is going to arise is less certain.

Profits and Losses

There is a common misconception that football clubs, especially those in the Premier League, are a licence to print money. Research shows that clubs in the Premier League only started to make profits from 2014/15 when Sky and BT increased the sums paid for broadcast rights by 70%. Clubs outside the top flight, especially in the Championship, lose large sums, and Bolton are no exception to this.

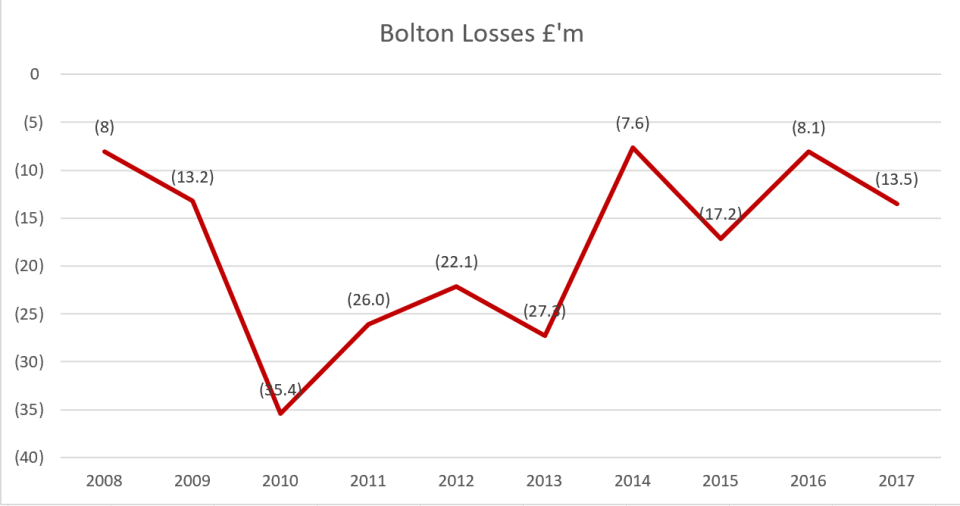

Over the course of the last decade Bolton lost £178.5 million, despite spending the first half of that period in the Premier League. These losses were initially absorbed by Eddie Davies, before he became too ill to continue. This is where Dean Holdsworth and Ken Anderson stepped in, although it seems the former was all fur coat and no knickers when it came to covering the day to day running costs, and the two fell out, resulting in Anderson obtaining majority control.

Ken Anderson deserves credit if he’s therefore been underwriting the trading losses, and cutting costs. There’s little evidence that Anderson has done anything than look after his own interests though.

His critics will no doubt point to the sale of players to offset these losses, the muddy waters on this should clear when the 2018 accounts are published.

If you are going to run a football club in the Championship then expect to incur substantial losses, as shown above. Ken Anderson has said that he’s not rich enough to take the club forward and is seeking external investment, but surely he must have known how much it costs to run a club in the Championship before becoming involved in Bolton.

Recent non-payment of wages (which Anderson claims to have now paid out of his own pocket), player strike threats and news of players loaned to Bolton having their wages paid by the host club, combined with a transfer embargo from the EFL suggest the club is struggling to pay the day to day costs.

Player trading

Bolton’s player purchases and sales history in recent years is a textbook analysis of a club that has fallen through the divisions.

In the Premier League the club was able to buy and sell players in multi-million-pound deals. Once relegated the initially the club buys players in an attempt to bounce back into the Premier League, and if this becomes unlikely then the purchases decrease and sales rise as the club needs to flog off the talent to pay the bills.

Funding

Football clubs can borrow from three broad sources, third party loans, director’s loans (which may or may not be interest bearing) and shares, which can in theory receive dividends if the club makes a profit, but in most cases don’t.

Whilst Eddie Davies was around Bolton were beneficiaries of his benevolence as he lent money interest free to the club he loved. This, as Tom Jones once said, is not unusual for local lads who have been successful in business, as clubs such as Huddersfield, Stoke, Brighton and Brentford will testify.

Another former director, Brett Warburton, (of the crumpet making baker family) has lent Bolton £2.5 million, but is charging interest at a rate that is far higher than he is likely to earn on his ISA.

Davies lent the club about £175 million, effectively summarised in the above table. He then in 2016 wrote off nearly all the sum due.

In September 2018, shortly before his death, Davies lent the club a further £4.8 million to allow it to pay off a loan due to Blumarble Capital Limited, a company with two employees and relatively few assets, apart from, according to its last recorded balance sheet, a loan due from another company of £4.8 million (almost certainly Bolton) and some cash. The Blumarble loan was arranged by Dean Holdsworth.

Blumarble effectively bought the loan from the liquidators of Sports Shield and have charged interest at 10% compared to 24% on the original loan.

Blu Marble was threatening to put Bolton into administration at the time. Eddie Davies’s loan came via a company called Moonshift Investments Limited based in the British Virgin Islands tax haven.

Ken Anderson has repeatedly said in his ‘notes from the Chairman’ column that Bolton have lower debts than most clubs in the Championship. This is true, but the credit for this should surely go to Davies rather than Anderson in writing off so large a sum, so it’s difficult why Anderson is so proud of himself over this issue.

Conclusion

Bolton’s is a tragic story, a historic and proud club whose name is continually being dragged into the mud. Fans just want to be able to see their team play some decent football with the certainty that there will still be a club in a month’s time, and that certainty is not presently guaranteed.

Ken Anderson claims that all is right, and that people should ignore his past in terms of running companies into the ground and being banned from being a director. Perhaps he is correct, all is Hunky Dory and HMRC, Stellar Football Limited (one of the world’s most successful sports agencies) the Insolvency Service, Forest Green Rovers, The Bolton News and all of the club blogs and fan groups have it wrong in terms of the club’s finances.

Straight answers are what are required to allay fears, but Anderson’s approach is one of snide whatabouttery in his Chairman’s notes column in the club program and website, which will I suspect result in a further loss of goodwill to a club that needs support from everyone in the game.

Anderson’s motives are unclear. If he wants to run the club then surely he should expect that it will lose money in the Championship, so whining about having to cover wages makes him no different to any other club owner in the division.

His other ambition may have been to flip the club by selling it at a profit to someone else, here we will have to wait and see the outcome.

As for his financial rewards from involvement with the club, they are high by League One standards but the club was promoted so he can argue were deserved.

If there were not subsequent alleged issues involving winding up orders and non-payment of staff or other clubs for loan fees payments to him become more difficult to justify.

One way to stop the brickbats is for Anderson to publish the 2018 accounts. Bolton will have had to submit them to the EFL for Profitability and Sustainability reasons (the new posh words for FFP), so there’s little reason to delay submission to Companies House. This could stop the criticism in its tracks if all is as rosy as Anderson claims, over to you Ken…

2 Comments

Roger Daniel

What a terrible shame.

A super club with a great history. The town, the people of Bolton need a club to be proud of.

Let’s see what the 2018 accounts say.

I understand there is a winding up order being presented on 8 May.

Good luck Bolton fans. You deserve better.

Kev Bumby

Now all is rosier; and K.A is no longer involved in the club, we can read this article with a sense of interest and comedy( Lee Anderson’s dress sense in particular) and see the bigger picture . Makes for interesting, but not very surprising reading.