Everton 2017/18: The Long and Winding Road

Introduction:

Farhad Moshiri, Everton’s new owner, had a busy year in 2017/18, sacking two managers and trying to make progress on a new stadium for the club.

After sacking Ronald Koeman in October 2017, the club’s fans grumpily tolerated the alehouse tactics of Sam Allardyce that took them from 13th to 8th in the Premier League, and then he too was jettisoned.

To an outsider this seems harsh, but phone ins and social media comments clearly indicated that Allardyce’s pragmatism in achieving results was not enough for a fanbase that had high expectations last season.

Spending restrictions under the previous owner Bill Kenwright were replaced with both managers splashing the cash as never before, and this trend has continued in 2018/19 under Marco Silva.

An analysis of Everton’s accounts shows that the club is in a far better place under Moshiri, but is this enough for them to challenge the ‘Big Six’ or should expectations be more focussed on being the best of the rest?

Key financial figures for year to 31 May 2018: Everton Football Club Company Limited

Income £189.2 million (up 10%).

Wages £145.5 million (up 39%) .

Operating loss £10.2 million (previous year £39.7million profit)

Player signings £214.6 million (up 133%)

Player sales £108.5 million (up 98%)

Owner loans £149.25 million

Income:

Matchday income for a club such as Everton tends to be the smallest element, but is essential for both financial fair play (FFP) purposes and if the club wants to challenge the established elite.

How to increase this income stream is tricky, as it can realistically can only be achieved by higher prices, more fixtures (such as through cup runs of qualifying for UEFA competitions)…or by moving to a bigger venue.

As can be seen from the above graph, Everton’s matchday income rose by 15% last season, as the club participated in, but did not progress too far, in the Europa League.

Selling tickets at competitive prices has always been a symbol of Everton’s traditional working class fanbase, and this is reflected in the relatively low total of £418 per fan, as the club’s stadium is not presently suited for prawn sandwich consumers.

Relative to Liverpool, Everton only generated 29 pence from each fan for every £1 of matchday income for their rivals from Anfield.

A move to Bramley Moore Dock, which is presently under discussion, is therefore essential if Everton have genuine ambitions at generating the level of income that will allow them to compete at the top table.

Nevertheless, it is difficult to see Everton attracting the number of football tourists, who are prepared to pay higher ticket prices and spend large sums in the merchandise store that will substantially boost matchday income, even if the club does move venues.

Commercial income for Everton rose by 60% in 2017/18, and the reason for this, according to the accounts, is that somewhat surprisingly Europa League income of €14.1 million was allocated to this source, as well as new shirt sponsorship deals from SportPesa and Angry Birds.

Income from UEFA is mainly in the form of central payments which are funded by TV companies, so it would seem logical to perhaps show this money as part of broadcasting income, although we would stress Everton have done nothing wrong with the way they accounted for this money.

Diving into the footnotes of the accounts shows that Everton’s commercial income also included £6 million again for sponsorship of the training complex from USM Services, the Ukrainian metal trading company that is partly owned by Farhad Moshiri, this has caused critics to question the commercial logic of such a deal and mutter about ‘financial doping’ of the accounts.

Finally, Everton generated money from broadcasting, and like most Premier League clubs, this is the main source of income.

As the club finished one place lower than the previous season, this meant that broadcast income was lower, as the formula for how it is allocated to clubs includes an element that is based on the final position in the table.

Relative to the clubs who finished around it the table, Everton were an attractive proposition to the TV companies in 2017/18, perhaps initially partly due to the Rooney factor, with 19 Premier League matches being shown live, one more than the previous season.

The club has been quoted as saying that the proportion of total income received from broadcasting fell to 69% in 2017/18 from 76% the previous season, but if UEFA prize money is included within broadcasting this figure has hardly changed.

So, overall, Everton’s income for 2017/18 was broadly in line with the club’s final position in the table and whilst the gap to the next club up (Leicester) will be eliminated as the Foxes are no longer in the Champions League, there is still a £120 million hole before Everton can catch up with Spurs, who will have the benefits of playing at Wembley and a new stadium to boost their finances.

Costs

The main costs for clubs are those relating to players, in the form of wages and transfer fee amortisation.

Whilst Everton’s income rose by 10% in 2017/18, it failed to keep pace with player related costs as the investment of players of the calibre of Sigurdsson, Pickford, Rooney, Walcott, Keane and Tosun came with associated wage demands. Normally there is a big wage jump in the first year of a new TV deal (which commenced in 2016/17) followed by relative stability, but this has not been the case for Everton as Moshiri released the handbrake on player recruitment.

Everton’s average weekly wage (and we fully accept that these are rough and ready figures) jumped from £49,000 to £70,000 a week, putting Everton substantially ahead of Champions League qualifiers Spurs (albeit Spurs figures are for 2016/17).

As a consequence, Everton’s wages to income ratio increased to 77%, meaning that the club was paying £77 in wages for every £100 of income.

It is not just players who have benefitted from the generosity of the owner, the highest paid director saw their income rise by 57% to £927,000.

By Premier League standards Everton’s board are reasonably well paid, but this pales into significance when compared to Daniel Levy’s package of over £6 million at Spurs, although Daniel’s fan club will no doubt point out this is partially linked to bonuses linked to his amazing success at delivering Spurs’ new stadium on time and budget.

The amortisation cost represents the transfer fee paid spread over the term of the contract signed by a player. So, when Everton signed Sigurdsson for £45 million on a five-year deal it meant that the amortisation cost is £9 million (45/5) a year for five years.

Everton’s annual amortisation cost has tripled since Moshiri acquired the club, showing the extent of his investment in the playing squad.

In using amortisation, it is possible to get a broader feel for a club’s longer-term transfer policy rather than just a couple of windows of buying a selling within an individual season. It would appear that Everton’s strategy is to try to compete with the big six in terms of player investment, although this is an arms race where you have to run to stand still as competing clubs constantly up the ante (apart from Spurs).

In using amortisation, it is possible to get a broader feel for a club’s longer-term transfer policy rather than just a couple of windows of buying a selling within an individual season. It would appear that Everton’s strategy is to try to compete with the big six in terms of player investment, although this is an arms race where you have to run to stand still as competing clubs constantly up the ante (apart from Spurs).

The substantial investment made in the fees paid for players meant that if amortisation costs are added to wages, it cost Everton £112 in player costs for every £100 of income generated, leaving nothing to pay the remaining bills of the club, unless there are substantial player sales too or an owner willing to underwrite the day to day expenses.

In terms of player sales, these were substantial, as the departure of Lukaku, Barkley and Deulofeu were the main contributors to a profit of £88 million. The danger with such an approach to funding the club’s day to day costs though is that sometimes it forces the club to be a seller, and also there are no guarantees that there will be buyers for your prize assets at the price you were hoping to sell them for.

Everton had some costs that fans will hope will not be repeated.

- Sacking Koeman and Allardyce, along with their entourages, did not come cheap, as the club has to pay out £14.3 million to show them the door at Goodison. It had cost the club £11.3 million in 2016 when Roberto Martinez was sacked.

- There were transfer fee write downs of £8.2 million, not sure who the players are, but no doubt Everton fans have their suspicions and will be able to finger them.

- The new stadium project progressed during the year, but as usual consultants, accountants, lawyers and other parasites had their snouts in the trough as things crystallised, and this cost the club a further £11.4 million, which hopefully will be money well spent if the plans come to fruition.

Everton borrowed substantial sums during 2017/18. Whilst Farhad Moshiri’s loans are interest free, the club also took out a £43 million loan secured on future TV revenues, and a couple of IOU’s from other clubs for transfers (almost certainly those of Manchester United for Lukaku) were used to borrow money from another lender. Consequently, the club ended up with an interest charge of nearly £120,000 a week on these loans.

Profits and Losses

Profit, if you ask the right accountant, is what you want it to be, and there are as many types of profit as there are flavours of Pringles.

A rough definition is that profit represents income less costs, and if this figure becomes negative it becomes a loss.

The headline figure in the Everton press release was a loss of £22.9 million, although this excluded all aspects of player trading, which, if included, would reduce the loss to £10.2 million, compared to a profit of £25 million in 2016/17. This figure is distorted by the one off factors such as manager sacking costs and profits on player sales that have been discussed above.

Stripping out the above distortions gives something called EBIT (earnings before interest and tax) profit, which is a better measure of recurring profits excluding the one-off volatile items.

Everton’s EBIT losses worked out at £1,232,000 a week in 2017/18, as the investment in player wages and transfer fees had such a significant impact on costs. This is far in excess of previous years, although could be seen as an investment in players for the future, and if it results in qualification for UEFA competitions could be substantially reduced in future seasons.

If non-cash costs such as player amortisation are stripped out, the position however improves, and Everton have an EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation) profit instead of a loss.

EBITDA is an important profit measure as it is the closest to a ‘cash’ profit that analysts use to assess a business and shows how much the club has to invest in player acquisitions from its day to day activities. Everton have made over £70 million in EBITDA profit over the last six years but have invested more than that in improving the squad.

Player trading:

According to the accounts Everton spent over £215 million in 2017/18 on player signings, and on top of that Wayne Rooney was recruited on a free transfer. This is almost as much as the club spent in the five previous years put together.

Even taking into account the record domestic transfer fee when selling Romelu Lukaku the net spend was still £106 million.

Compared to their peer group, Everton’s spending is very much as the top end of the table.

Since the end of the season the board have backed new manager Marco Silva with a net £83 million on new signings such as Richarlison.

Funding the club

Clubs usually have a choice between third party loans (which attract interest payments) owner loans (which may or may not charge interest) and shares (which occasionally pay dividends).

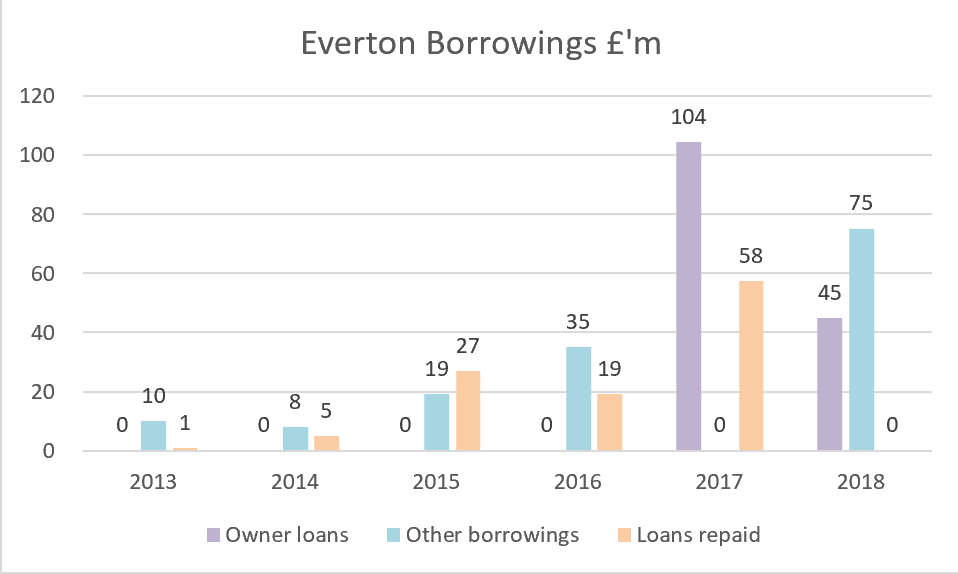

In the case of Everton, the club have focussed on owner loans and short term interest-bearing loans.

On top of the sums borrowed in 2017/18, the footnotes revealed that Farhad Moshiri has lent a further £100 million to the club since May 2018. This money has presumably been invested in new players and the ongoing application for a new stadium.

Conclusion

Under Moshiri Everton have certainly moved to a new level of investment, mainly in terms of the playing squad. This wasn’t particularly successful in 2017/18, but there are signs of improvement under Marco Silva as the squad starts to gel together.

Whilst the club is playing at Goodison there is little scope to increase income, and every year until a new stadium is open for business will increase the gap between the club and the ‘Big Six’, all of whom have competitive advantages in terms of income generating capacity and facilities.

Until the new stadium arrives, unless Moshiri is willing and able to underwrite substantial losses (which could cause financial fair play problems should Everton qualify for UEFA competitions) then realistically seventh place and entertaining football is the realistic target for the club.